Architect and designer. Born in 1967, Naoki Terada graduated from the Department of Architecture at Meiji University in 1989. He completed his studies at the Architectural Association School of Architecture in London in 1994, and has since returning to Japan worked widely across fields including architecture, interior design, product design, and sign design. He has also served as a producer and director for brands. He established Terada Design Architects in 2003 and the Terada Mokei product brand in 2011, opening a Terada Mokei shop in 2013. Between 2018 and 2024, he served as CEO of Inter Office Ltd. He is the recipient of several awards, including the Good Design Award, and the author of The Book of Terada Mokei: How to enjoy paper model of 1/100 scale (2011) and an expanded edition of the same title (2015), both published by Graphic-sha. https://naokiterada.com/

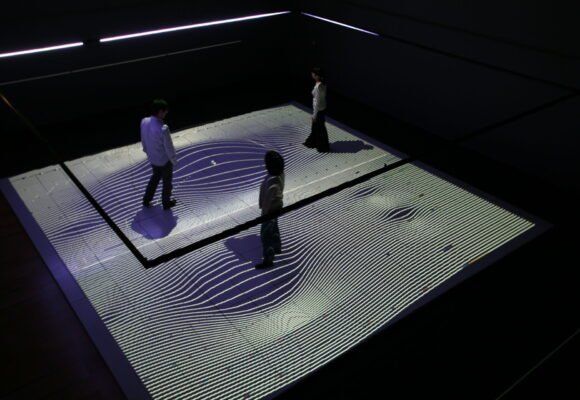

Installation view: Fujikura+Omura, Pavilion of JAPAN 2F, Pavilion of JAPAN In-Between, 19th International Architecture Exhibition of La Biennale di Venezia Intelligens. Natural. Artificial. Collective. Photo by: Luca Capuano Courtesy: La Biennale di Venezia

To my embarrassment, I had never attended the Venice Biennale of Architecture before.

From the touristy bustle of Piazza San Marco, I rode the vaporetto (water bus) for a few stops to reach the lush Giardini. This garden, lined by pavilions representing countries around the world, serves as the Biennale’s main venue. What makes the Biennale unique is that each country presents its exhibition in an existing pavilion, with the premise that the exhibition and presentation is to take place within that space; no new structures are allowed. Hence, architecture is presented within the constraints of each pavilion’s interior. Moreover, the pavilions were all designed by renowned architects. For example, the Finnish Pavilion (1956) is the work of Alvar Aalto, one of Finland’s most celebrated architects, who also designed furniture for Artek; the Dutch Pavilion (1953) was conjured up by Gerrit Thomas Rietveld, noted for building the Schröder House in Utrecht and for his role in the De Stijl movement; the Venezuelan Pavilion (1954) was designed by Venetian master architect Carlo Scarpa; and the Austrian Pavilion (1934) by Josef Hoffmann, one of the founders of Vienna Secession. One might call it a gathering of the gods of architecture. I imagine that curators and directors must find it rather challenging to decide how to utilize these distinctly quirky exhibition spaces.

The theme of the 2025 Biennale is “Intelligens. Natural. Artificial. Collective.” I noticed a great many exhibits that, in line with the theme, dealt with topics such as the environment and human rights.

Pavilion of DENMARK Build of Site, 19th International Architecture Exhibition of La Biennale di Venezia Intelligens. Natural. Artificial. Collective. Photo by: Marco Zorzanello

Spanish Pavilion

Themed “Internalities,” the exhibition highlights architectural ecosystems rooted in the Spanish regions and is the result of joint research by a team of architects, scholars, and photographers from throughout the country. Focusing mainly on wood, the exhibition showcases a cycle covering the material’s production, transportation, construction, and disposal, and employs a great many models and photographs to discuss decarbonization and “internalities,” or mechanisms that allow for this cycle to be completed within a specific region. Given that this is an architecture exhibition, the sheer number of models made for reassuring viewing.

Danish Pavilion

Labeled “Build of Site,” the Danish exhibition showcases the renovation of the Danish Pavilion. As most of the pavilions were built in the 1950s, the need for renovation work has increased significantly in recent years, with the buildings having to be made accommodating for present-day exhibitions, as well as accessible, air-conditioned to cope with climate change, and resistant to the rising tide levels in Venice. The main exhibition at the Danish Pavilion, where the floor was raised to prevent flooding, focuses on the reuse of waste materials from the construction site. For example, tables made from soil from under the floor, mixed with waste gelatin sourced from fisheries in the Adriatic Sea, are on display. Instead of repeating a scrap-and-build process of construction for short-term events and using materials brought in from the outside, the exhibition embodies a hyper-local, sustainable approach to architecture, in which only resources available within the pavilion itself are reused.

Pavilion of NETHERLANDS (The) Sidelined: A Space to Rethink Togetherness, 19th International Architecture Exhibition of La Biennale di Venezia Intelligens. Natural. Artificial. Collective. Photo by: Luca Capuano Courtesy: La Biennale di Venezia

Dutch Pavilion

The “Sidelined” exhibition presents an alternative to the traditional sports bar. Sports foster a sense of unity among groups and promote the formation and strengthening of identity, but they also often cause division and conflict. The exhibition proposes a new fictional team sport as a tool for the future, thereby presenting a vision of an inclusive and prosperous society. Both the organizers and attendees wear yellow and purple uniforms and scarves, creating a sense of unity.

German Pavilion

Titled “Stress Test,” this exhibition is themed on global warming, with visitors having to pass through a high-temperature laboratory upon entry—a literal stress test. This is followed by high-definition imagery and graphics depicting ongoing climate change in real time, forcing visitors to confront the situation we currently find ourselves in. Solutions were also presented, making for an exhibition I would love for President Trump to see.

Pavilion of NORDIC COUNTRIES (FINLAND, NORWAY, SWEDEN) Industry Muscle: Five Scores for Architecture, 19th International Architecture Exhibition Photo by: Marco Zorzanello Courtesy: La Biennale di Venezia

Nordic Pavilion

“Industry Muscle.” A transgender artist performs in a rugged space featuring cars impaled on concrete pillars, steel shelters, and graffiti on glass surfaces. The exhibition speaks out against standardized architecture from a trans perspective, challenging the idealism of Modernism. Conscious of the social and political aspects of architecture, the exhibition also reexamines the question of who architecture is for.

Pavilion of POLAND ‘Lares and Penates: On Building a Sense of Security in Architecture’ 19th International Architecture Exhibition of La Biennale di Venezia Intelligens. Natural. Artificial. Collective. Photo by: Luca Capuano Courtesy: La Biennale di Venezia

Polish Pavilion

Named “Lares and Penates: On Building a Sense of Security in Architecture,” this heartwarming exhibition references the guardian deities of ancient Roman households. As suggested by the subtitle, it touches on the many objects that provide us with a sense of security, all contained within the concept of shelter—the building of which is the original purpose of architecture.

For example, traditional household charms include candles placed near windows to protect homes from lightning (gromnica in Polish), wreaths hung at construction sites to prevent accidents (wiecha), and horseshoes hung in a “U” shape to prevent good luck from “falling out.” As for modern guardians, fire extinguishers are displayed in niches as if they were frescoes, as are security cameras and numerous evacuation signs, to name only a few. Together they make for an enjoyable exhibition that conveys a distinct sense of security while offering insights into its cultural and social background.

Japan Pavilion

And then there’s the much-anticipated Japan Pavilion, which attracted a great deal of attention due to its exhibition—a presentation very different from those of the other pavilions, and one that can be somewhat challenging to understand.

Built in 1956, around the same time as most of the other pavilions, the Japan Pavilion was designed by Takamasa Yoshizaka, who studied under Le Corbusier. There is no entrance at the front, with visitors having to walk around the garden to access the exhibition rooms; a layout that led to the building being described as Japanese in style. Its ground-level piloti leave room for an outdoor space in which sculptures can be exhibited. Meanwhile, the exhibition room on the second floor is supported by four wall pillars arranged like the sails on a windmill. Visitors can look down on the piloti through a square hole in the center of the floor, while light pours in from a glass-block skylight in the ceiling directly above. A bold marble floor pattern adds to the challenging nature of the venue, and it’s said that Yoshizaka beseeched exhibiting artists to “create works that can stand up to this space.”

And in 2025, that very space hosts an exhibition titled “In-Between ” I was curious to see how a contemporary exhibition and concept could be interwoven with the modern architecture of the period of rapid economic growth, which took place some 70 years ago.

Serving as curator is the architect Jun Aoki, who heads up AS Co. Ltd. and is noted for his work both in Japan and overseas. The curatorial advisor is Tamayo Iemura, an independent curator and a professor at Tama Art University, while the exhibitors include Sunaki, an architectural unit composed of Taichi Sunayama and Toshikatsu Kiuchi, and the artist-and-architect duo of Asako Fujikura and Takahiro Ohmura.

“In-Between” poses questions about the relationship between humans and generative AI. The exhibition wrestles with the concern that society could soon become dependent on a seemingly infallible AI, exploring how we should interact with artificial intelligence—or rather, how we might keep a proper distance from it. It posits that we should do away with the idea of one side being subordinate to the other, instead encouraging humans and AI to engage in what Aoki calls the “awkward” dialogue of making mistakes together.

Installation view: Sunaki, Pavilion of Japan 1F, Pavilion of JAPAN In-Between, 19th International Architecture Exhibition of La Biennale di Venezia Intelligens. Natural. Artificial. Collective. Photo by: Luca Capuano Courtesy: La Biennale di Venezia

The exhibition begins with Sunaki’s “actual” works along the handrails of the approach, leading visitors to the second-floor entrance. Upon entering the exhibition room, they are then overwhelmed by a “fictional” video work by Asako Fujikura and Takahiro Ohmura. Looking down through the hole on the second floor, you see the first floor below. Descending the slope, you then arrive at the “actual” work in the first-floor pilotis that was visible through the hole. Finally, by looking up at the opening to the second floor above the first-floor piloti, one can sense a correspondence between the “fictional” and the “actual” across the floors. Looking back, this correspondence, or relationship, felt somewhat awkward. It leaves the viewer room to insert their own questions. And this sense of awkwardness can be felt both in the individual works and between them. It’s a feeling that extends to Yoshizaka’s architecture, i.e. the Japan Pavilion.

“Awkward” is an apt word to describe the aftertaste of that dialogue—between humans and AI, between the fictional and the actual, between art and architecture.

The Modernist movement in architecture and product design emerged in the early twentieth century, driven by the Industrial Revolution and premised on mass production. By the 1970s, its entirely valid claims had nonetheless led to a buildup of discomfort and fatigue, compounded by doubts about petroleum products sparked by the oil crisis and political and social skepticism exposed by the Vietnam War. These factors converged to give rise to the Postmodern movement. However, postmodernism too faded away like a fleeting fever, and today environmental and human rights issues have become the driving forces behind design.

Amid such change, attending the Biennale made me question the exhibition’s concept of pitting country-specific boxes against each other in an Olympics-style format, all while feeling like the national characteristics of the participating countries stood out in relief. The Scandinavians presented a shocking vision of the future while maintaining a commitment to environmental and human rights issues, while the Germans confronted the present head-on and offered a raw, unfiltered perspective. The Latins and Slavs used wit to shift the focus, while Japan defied European standards. The Japanese exhibition deserves to be called unique, delving into the future of AI and being the only one to pose questions rather than offer solutions.

To summarize my experience, I felt that while a society that values diversity is what everyone is striving for, there is a sense of a uniform moral code being imposed. “The electricity used to operate this pavilion is generated by solar panels.” “All materials will be recycled after the event.” These are not goals in and of themselves, but rather means to an end, and in order to ensure that our goals are achieved, the means should be the most effective ones available. Perhaps what we really should believe is that, as alluded to at the Japan Pavilion, the very act of questioning and experimenting is the most promising means of shaping the future. While we must acknowledge the urgency of the situation—that we have limited time to change the future—I believe there is still room for trial and error to arrive at the most effective means, and that we should avoid rushing to hasty conclusions.

Translated by Ilmari Saarinen

INFORMATION

Report from the 19th International Architecture Exhibition Venice (Venice Biennale of Architecture)

19th International Architecture Exhibition Venice (Venice Biennale of Architecture)

Dates: May 10 to November 23, 2025

Venues: Giardini, Arsenale, etc.

Curator: Carlo Ratti

Official website: https://www.labiennale.org/en/architecture/2025

Pavilion of JAPAN

Title: In-Between

Organizer: Commissioner/The Japan Foundation

Curator: Jun Aoki (architect, AS Co. Ltd.)

Curatorial advisor: Tamayo Iemura (independent curator, professor at Tama Art University)

Exhibitors: Asako Fujikura + Takahiro Ohmura, Sunaki (Toshikatsu Kiuchi & Taichi Sunayama)

Official website: https://venezia-biennale-japan.jpf.go.jp/j/architecture/2025