Photographer and critic, born in 1960. Professor at Tama Art University, Department of Information Design, and member of the Institute for Art Anthropology. A specialist in visual anthropology, his activities connect various types of media, including photography, text, and video installation. Has worked with, published on and curated themes such as memory, movement, and the masses, and directed international exhibitions in both Japan and elsewhere. Served as the commissioner of the Japanese pavilion at the Venice Biennale 2007 and as Artistic Director of the Aichi Triennale2016.

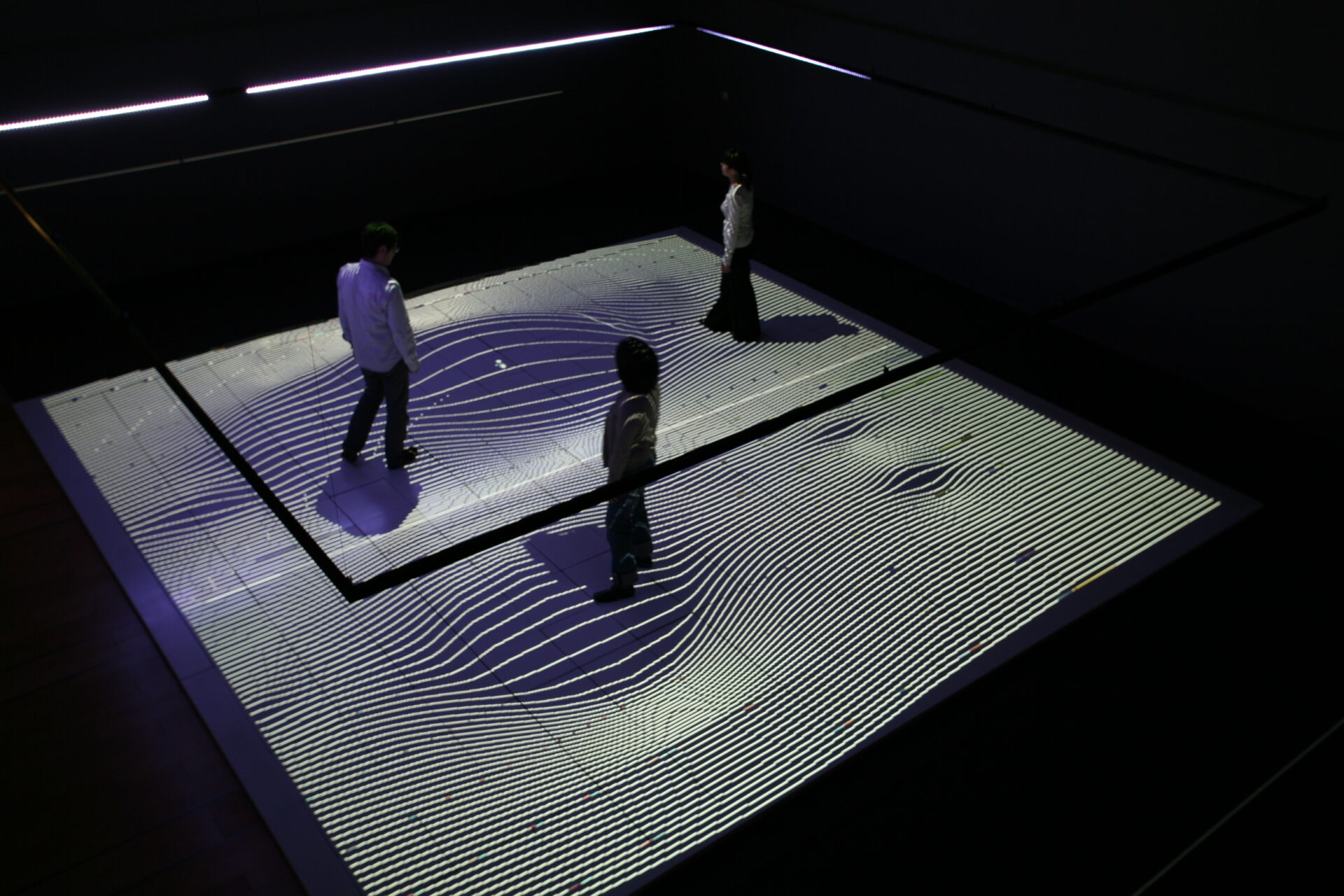

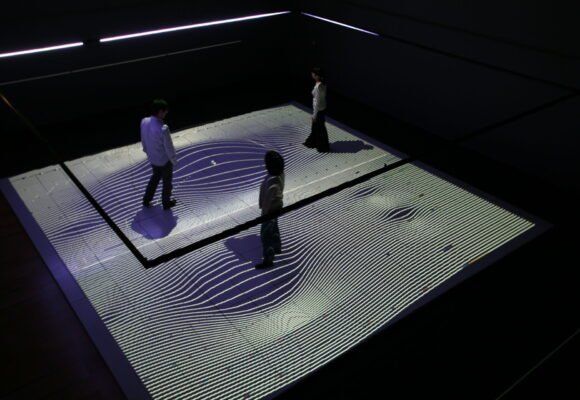

MIKAMI Seiko “gravicells — gravity and resistance” 2004 Photo: KIOKU Keizo Photo Courtesy: NTT InterCommunication Center [ICC]

When gazes, hands, and hearts assemble

This is a long-awaited exhibition. Since Seiko Mikami’s sudden passing in 2015, there have of course been some opportunities to encounter her work. Gallery exhibitions have been held to coincide with the restoration of her works and their acquisition by museums. Furthermore, a framework for preserving her legacy has been developed little by little by way of joint research between the Yamaguchi Center for Arts and Media (YCAM), where Mikami created her works from 2000 onward, and Tama Art University, where she taught; and thanks to the establishment of the Seiko Mikami Archive in the Tama Art University Art Archives Center. However, interactive works premised on audience participation are, quite obviously, rendered non-existent without the opportunity to experience them. That Mikami’s work has nearly been forgotten in the art world over the past decade, to the point where even students majoring in media art have never heard her name, may in a sense indicate the inherent fate of interactive art: if it cannot be experienced, it might as well not exist.

The defining feature of this exhibition is its remarkable convergence of time, place, and people. In his opening remarks, Akihiro Kubota—who spearheaded the collaborative research for the project and has dedicated himself to organizing the Seiko Mikami Archive—stressed the importance of young viewers experiencing this work today. This signifies that the opportunity us contemporaries of the artist have long awaited has finally materialized. The convergence I mentioned occurred in the 10th anniversary of Mikami’s passing, at the NTT InterCommunication Center [ICC]—the very institution that commissioned for its permanent exhibition her piece “World, Membrane and the Dismembered Body” upon its opening in 1997. It brought together numerous individuals involved in the creation and recreation of Mikami’s major installation works: “gravicells — gravity and resistance,” “Desire of Codes,” and “Eye-Tracking Informatics.” An exhibition brought to life by such a concentration of artists and technical experts active at the forefront of media art is a rare occasion indeed, and I can’t help but hope that audiences will not miss this once-in-a-lifetime opportunity.

As for the content of the works, you are best off referring to the meticulously crafted exhibition website. After all, what matters most in Mikami’s work is feeling; information for understanding her pieces is largely unnecessary. Her installations strip away the superfluous to the extreme, allowing the viewer to perceive time, place, and the body through experience. That said, I would like to briefly introduce the key works here while touching upon what questions the exhibition poses, including some of my own thoughts as well. If I were to name a few keywords, they would be “update,” “archive,” and the “mausoleum” referenced in the exhibition title.

MIKAMI Seiko “gravicells — gravity and resistance” 2004 Photo: KIOKU Keizo Photo Courtesy: NTT InterCommunication Center [ICC]

Now, I referred to the “fate” of interactive art above, and the production years listed in the captions for each work illustrate my point. Let’s start with “gravicells — gravity and resistance.” In this work, when participants step onto the floor, sensors beneath detect their weight and the tilt of their bodies. The resulting changes in force exerted across the floor are expressed as sound and the warping of contour-like lines projected onto a screen. Through a visual representation of gravity—a force we normally don’t consciously perceive—alongside those of bodily movement and speed, the work prompts us to re-recognize the forces underpinning our experiential world. The production year is listed as “2004/2010/2025.” After the work’s initial release in 2004, it was updated in 2010, when the LEDs around the floor were replaced with video projections. This exhibition features the original 2004 version.

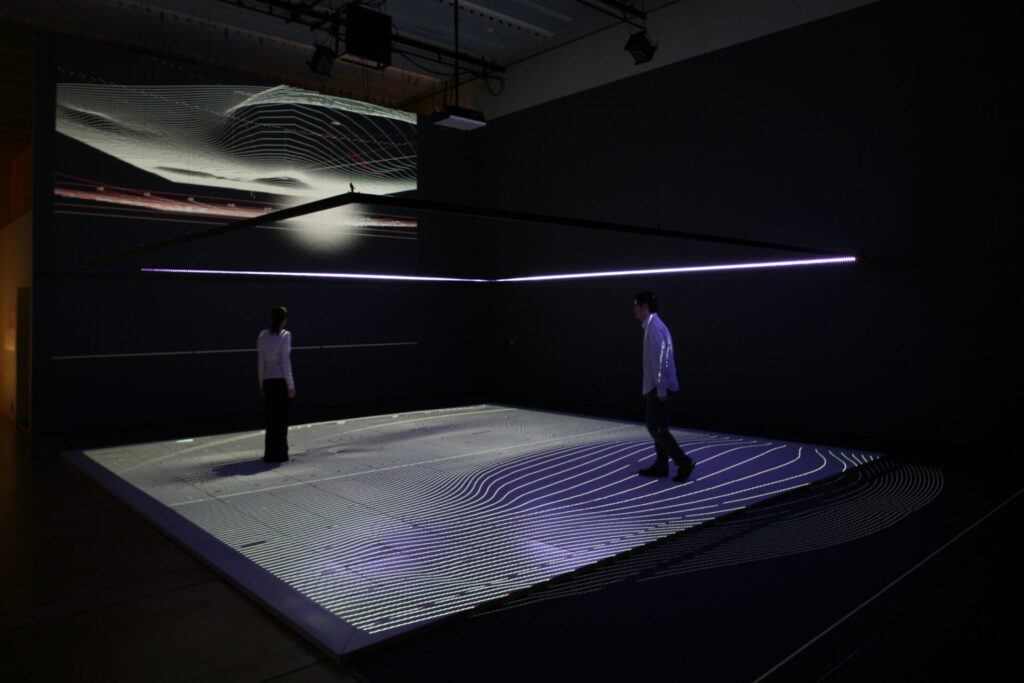

MIKAMI Seiko“Desire of Codes” 2010/2011 Photo: KIOKU Keizo Photo Courtesy: NTT InterCommunication Center [ICC]

MIKAMI Seiko“Desire of Codes” 2010/2011 Photo: KIOKU Keizo Photo Courtesy: NTT InterCommunication Center [ICC]

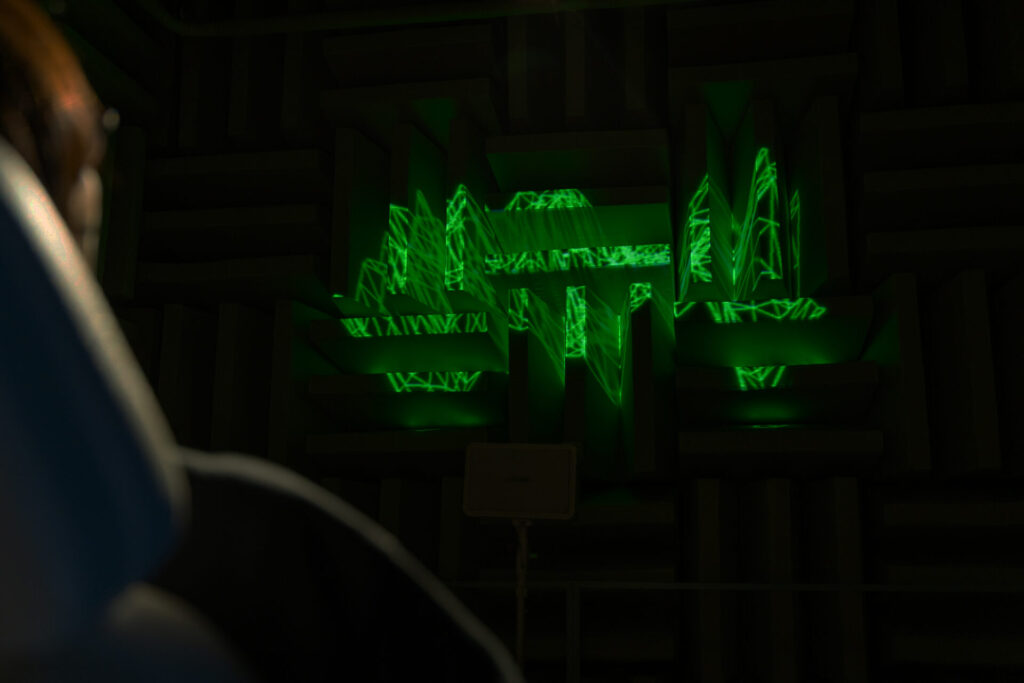

The largest installation work on display, “Desire of Codes,” was commissioned by YCAM, premiered in 2010, exhibited at ICC the following year, and then restored by YCAM over the two years following Mikami’s death. It explores the relationship between human perception and desire in a high-information society, and is composed of three parts: “Wriggling Wall Units,” “Multiperspective Search Arms,” and a “Compound Eye Detector Screen.” Video footage captured inside and outside the exhibition space, along with information gathered from networks, is reconfigured and projected onto a mesh-like screen resembling the compound eye of an insect. Featuring search arms that move in response to viewers walking through the space, the installation represents an uncanny reality: we are constantly being watched somewhere, while the information thus gathered influences our perception, blurring the distinction between subject and object and manipulating our desires. While the work seems to anticipate the modern-day “attention economy,” the information gathered from the internet has certainly changed significantly since its initial presentation. Perhaps the very structure of this large-scale installation has become embedded in the minutiae of our daily lives.

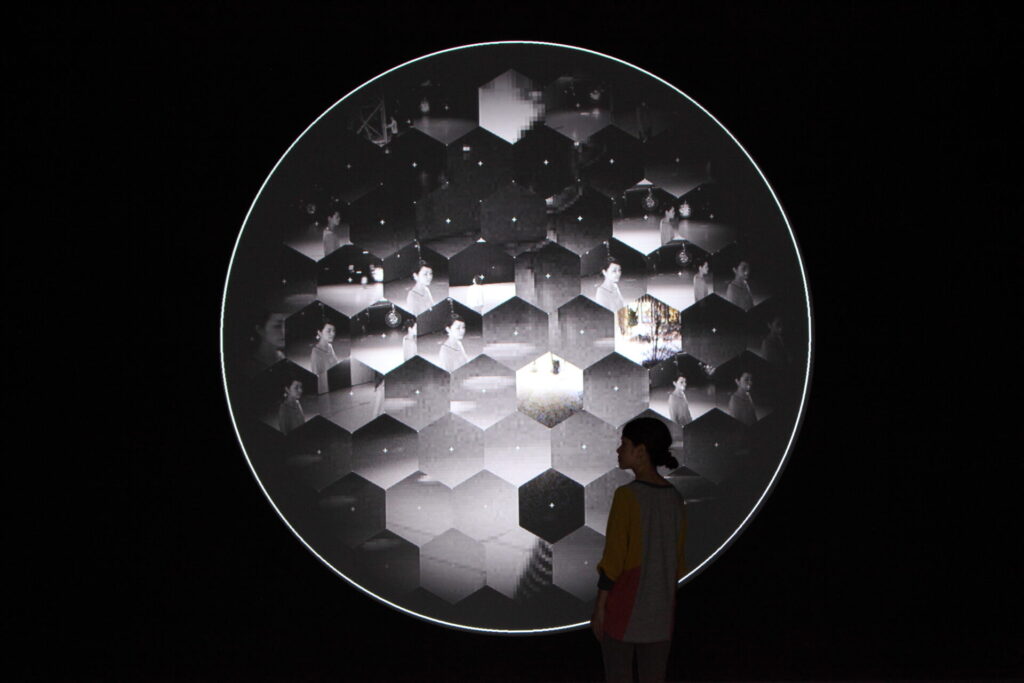

MIKAMI Seiko “Eye-Tracking Informatics” 2011/2019 Photo: KIOKU Keizo Photo Courtesy: NTT InterCommunication Center [ICC]

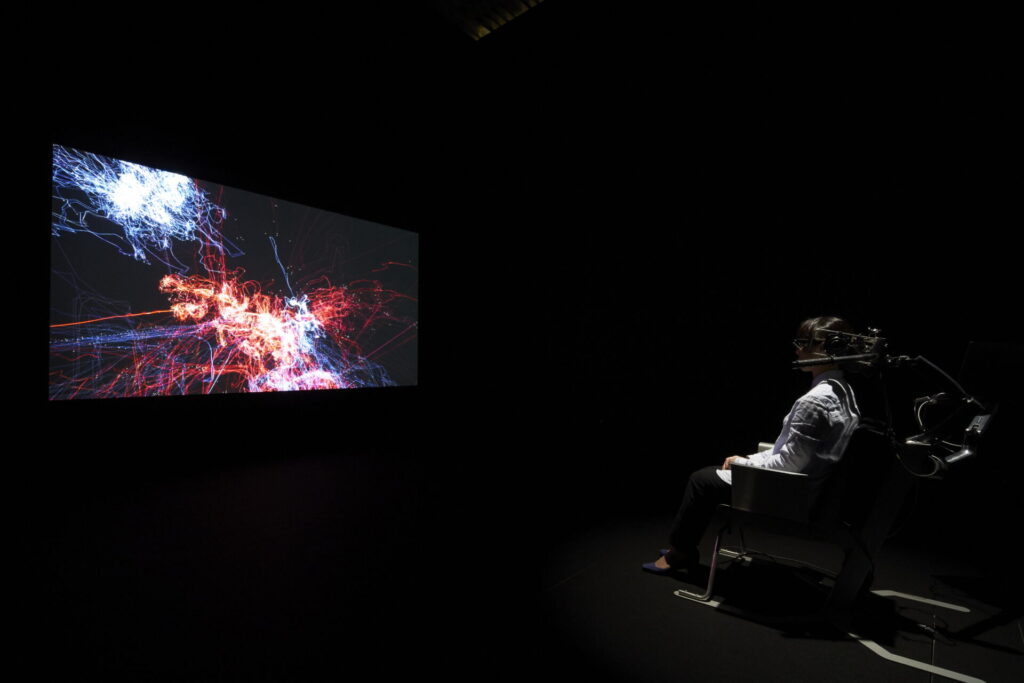

The work that has undergone the longest development period since its initial presentation, including updates and remakes, is “Eye-Tracking Informatics.” Based on Mikami’s initial work “Molecular Informatics—Morphogenic Substance via Eye Tracking,” created at Canon ARTLABb in 1996, it underwent several version updates and was exhibited around the world before the artist, commissioned by YCAM, remade it in 2011 as “Eye-Tracking Informatics.” The work’s concept is “seeing the act of seeing.” Looking back, I was fortunate to have experienced the 1996 version, but re-experiencing the trajectory of the gaze thirty years later—tracking it with my own gaze, as it were—felt completely free of temporal dissonance, thanks to the improved speed at which the projected trajectory was drawn. Furthermore, the reconfiguration of the sound system to produce three-dimensional audio resulted in an experience whose depth seemed to linger physically within me. This exhibition features the remade version presented at Tama Art University in 2019, updated and restored by YCAM.

Installation view “Toward a Mausoleum of Perception: MIKAMI Seiko’s Interactive Art Installations” Photo: TOMITA Ryohei Photo Courtesy: NTT InterCommunication Center [ICC]

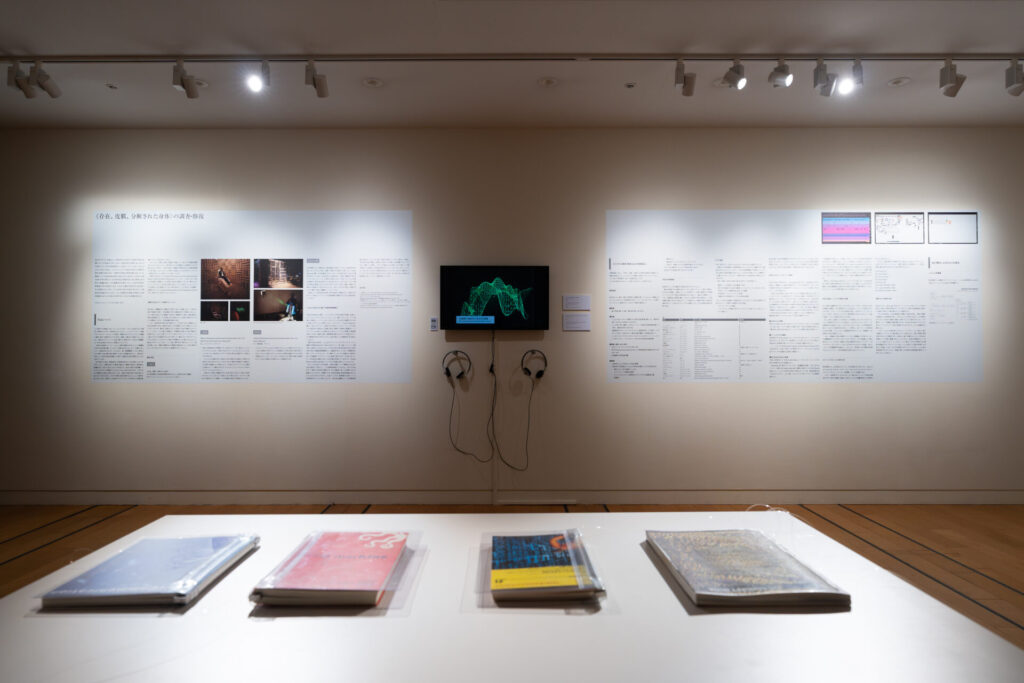

What these representative works share is a mechanism and form through which the participant becomes part of the work. This was something the artist herself recognized clearly: intervention by participants and viewers recursively alters the state of the work, in some cases affecting subsequent participants or viewers. The exhibition meticulously documents the history surrounding the works: their updates, restorations, and remakes. Notably, a great many people were involved in each of these histories, the display of which is made possible by the aforementioned Seiko Mikami Archive at Tama Art University and its associated database. Fittingly for an exhibition characterized by updates and restoration, the extensive Seiko Mikami Chronology displayed in the center of the venue represents the state of the archive as of 2025. In the sense that it will continue to grow by absorbing even more information going forward, it deserves to be called a living archive.

In closing, I’d like to touch on the exhibition title, “Toward a Mausoleum of Perception.” It was taken from the following passage written by Mikami in a collection of works published in Spain:

“What I envision for the future is to exhibit all my perception-related projects as interactive installations. This will become a museum (or mausoleum) of perception.”

Whether Mikami wrote this passage in Japanese or English is unclear. Therefore, what follows is pure speculation, but provided it was written for an exhibition in Europe, one would guess that she used the term to evoke a magnificent burial site. The word “mausoleum” derives from the monumental tomb of Mausolus, a king of the Persian Achaemenid Empire. Mausoleums exist in various forms, ranging from religious structures to facilities enshrining twentieth-century political leaders. In terms of scale and symbolism, the Egyptian pyramids stand as the world’s greatest mausoleums and have profoundly influenced mausoleum architecture worldwide.

Although their contexts and histories vary, what distinguishes a mausoleum from a simple tomb is its profound connection to the idea of the immortality of the soul—the belief that the soul of the deceased is welcomed into a spirit realm where it lives on alongside other spirits. The ancient Egyptian view of life and death is particularly well-known, and I once encountered a work from that era in an unexpected place. In 1985, at the entrance to the “Les Immatériaux” media art exhibition held at the Centre Pompidou in Paris, stood a relief unearthed near the Karnak Temple Complex in Egypt. The beautiful sculpture depicts a goddess sending a token of life to the pharaoh, and I believe Jean-François Lyotard and his fellow curators used this image to allude to forms of media that embody life and meaning.

MIKAMI Seiko “World, Membrane and the Dismembered Body” (reproduction of the sound installation version) 1997 Photo: TOMITA Ryohei Photo Courtesy: NTT InterCommunication Center [ICC]

My book The Infragram is a critical examination of contemporary visual culture through five chapters, each guided by the work of Seiko Mikami. I used an image of the recently restored “Eye-Tracking Informatics” for the cover, and in the book’s introduction mentioned this Egyptian relief. I recalled it now since the feeling of immortality suggested by the “Mausoleum” title seemed to linger as a latent theme of the exhibition.

If this “mausoleum of perception,” distinct from both religious and political mausoleums, were to be associated with immortality, then that would have to be done by reference to updating and archiving. The restoration and preservation of artworks by others requires not only technical skill, but also a gaze and heart of tender care. If the gazes of participants and viewers feed back into the work, if updates and repairs are carried out by numerous hands when needed, and if the totality of this is archived, then might we not rephrase this practice itself as a “collective soul”? I find myself imagining such a thing.

I sincerely hope that this exhibition, brought into being by the gathering of many eyes, hands, and hearts, will continue to grow as it travels to new locations.

Translated by Ilmari Saarinen

INFORMATION

Toward a Mausoleum of Perception: MIKAMI Seiko’s Interactive Art Installations

Date: December 13, 2025 - March 8, 2026

Venue: NTT InterCommunication Center [ICC]

Organizer: NTT InterCommunication Center [ICC] (NTT EAST, Inc.)

Cooperation: Tama Art University Art Archives Center