Toshiro Inaba, M.D., Ph.D. Born in Kumamoto in 1979. Cardiologist and Assistant Professor at the Department of Cardiovascular Medicine of the University of Tokyo Hospital from 2014 to 2020. Since April 2020, holds the roles of Head of the Department of General Medicine at Karuizawa Municipal Hospital, Associate Professor at the Shinshu University Research Center for Social Systems, Visiting Researcher at the University of Tokyo Research Center for Advanced Science and Technology, and Visiting Professor at the Tohoku University of Art and Design. Inaba was also appointed Artistic Director of the 2020 Yamagata Biennale, and is involved in home medical care and mountain medicine. He engages in active discussion with professionals in a wide range of fields in order to bring about new medical and social solutions. His publications include “Inochi o Yobisamasu Mono” (Anonima Studio), “Korokoro Suru Karada” (Shunjusha), and “Karada to Kokoro no Kenkogaku” (NHK Publishing). Website: https://www.toshiroinaba.com/

What the path of fantasy is telling us

Director Nobuhiko Obayashi passed away right after finishing his last film. In fact, the day of his death – April 10, 2020 – was also the planned premier date for his swansong, titled Labyrinth of Cinema. Its release was delayed on March 31 due to the Covid-19 coronavirus outbreak, and Obayashi left this world only days later. What did the director, who had dedicated his life to the gods of cinema, spend a lifetime trying to tell us through his medium? I had a vague feeling that there’s something we need to take away from Obayashi’s movies in these trying times.

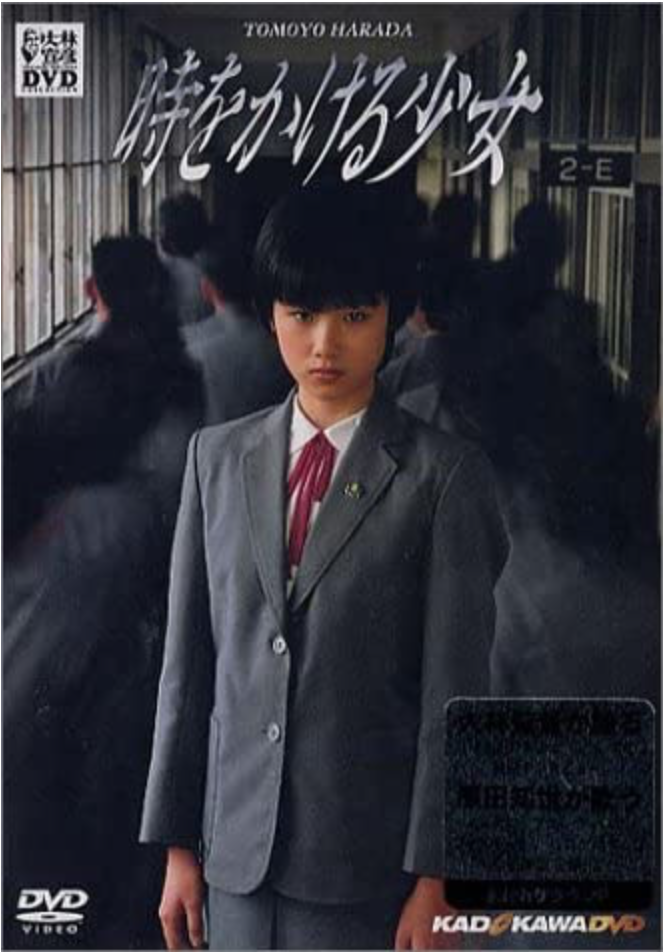

I decided to re-watch The Girl Who Leapt Through Time (1983). Leaving all my prejudices at the door, I faced this film with fresh eyes. It’s a story of a girl in the first year of high school who “leaps” back through time. After smelling the scent of lavender, she is cast into a world where time is distorted. The same day repeats itself over and over, and yesterday becomes today once more. As past and present blend together, so do life and death. In this strange timeline, a certain encounter and experience strongly convince the girl to return to normal life again. All of a sudden, time is distorted no longer. It’s as if the protagonist is back in the world she came from. But having returned by passing through a different domain, the girl can now see into a world entirely her own: the world of the soul. She takes that world to heart and protects it as if it were her child, becoming her own woman in the process.

Adolescence is a time when a child’s entire, painstakingly crafted view of his- or herself is turned completely on its head. It is a necessary step if one is to enter the uncharted world of adulthood, but it is also something that takes place deep down in one’s inner self, and an entirely inexplicable experience. Because these changes are difficult to put into words with a child’s vocabulary, they sometimes surface in the form of problematic behavior. Most adults, having forgotten what it’s like to be a child, are unable to properly pick up on these signals. Children are sensitive to the world of the soul; it can be said that children’s eyes are those that truly see into this world. When we grow up to become adults, our inner eye gradually closes to the world of the soul. Are adults, then, unable to see into this world for good, or can the connection be restored? I think we can impart a bit of the soul by talking about fantasy. This can take the form of movies, art, or music. In other words, the soul uses the path we call “fantasy” to tell us something. (Perhaps this is the period called “the autumn of our lives.”) [Note: as opposed to the “spring” of adolescence.] The Girl Who Leapt Through Time rides this pathway of fantasy, traveling through time to knock on the door of our adolescence, as if waking a small animal from its sleep. It asks us: “What is your soul looking at now?”

Obayashi was known for his unorthodox staging methods. He prohibited his cast from acting as if they were machines following the “orders” of the script. He demanded they “live” their roles instead of merely acting them. The director would only present a philosophy, not give any specific acting answers. The set was a place of constant change, and Obayashi told his cast and crew to adapt – even the script itself was subject to change. Actors and crew members unfamiliar with this method would reportedly get quite upset. Obayashi’s films, however, catapulted many actors – including Tomoyo Harada and Tadanobu Asano – to stardom.

I think Obayashi’s message was that the creative process of making a movie requires everyone’s participation and input. Besides the cast, this includes the cinematographers, the audio crew, the assistants; Obayashi wanted everyone to put their heads together and move each other’s feelings.

I feel like Obayashi’s testament to our time, what he wanted to tell us, is something similar to what I just described. In other words, his message is that in society as well as in the medical profession, we need to emphasize the sharing of philosophies, get everyone in this world to share their concerns as creative participants, and think together. The economy is stalling, people are losing their jobs, the medical infrastructure is being overwhelmed – problems abound around us. For that very reason, you need to think; there’s no one right answer; that’s why you need to keep thinking. And the philosophy to adhere to? It’s life itself, isn’t it?

It is said that Obayashi was, throughout his life, deeply affected by something Akira Kurosawa told him in his youth. This was the idea that people who have experienced war should speak up about its horrors and lack of meaning. Feeling that his earlier films had not faced that issue directly, Obayashi said that his last few works –Hanagatami (2017) and Labyrinth of Cinema (2020) – were intended to address this concern.

Sure, The Girl Who Leapt Through Time can, at a glance, be called a teen movie, a sci-fi flick, or a fantasy story. But watching it again made me think of it also as a requiem for the dead. It’s a story told eloquently with silence. Obayashi’s “soul,” walking the path of fantasy, “leaps through time” to speak directly to our chaotic age. Whether we choose to listen is up to us.

Translated by Ili Saarinen