Hiroki Yamamoto, born in Chiba in 1986, is Lecturer at Kanazawa College of Art in Japan. Yamamoto graduated in Social Science at Hitotsubashi University, Tokyo in 2010 and completed his MA in Fine Art at Chelsea College of Arts (UAL), London in 2013. In 2018, he received a PhD from the University of the Arts London. From 2013 until 2018, he worked at Research Centre for Transnational Art, Identity and Nation (TrAIN) as a postgraduate research fellow. After working at Asia Culture Center (ACC) in Gwangju, South Korea as a research fellow and The Hong Kong Polytechnic University, the School of Design as a postdoctoral fellow, he was Assistant Professor at Tokyo University of the Arts until 2020. His publications include The History of Contemporary Art: Euro-America, Japan, and Transnational (Chuo Koron Sha, 2019), Media and Culture in Transnational Asia: Convergences and Divergences (Rutgers University Press, 2020), and Thinking about Racism (Kyowakoku, 2021).

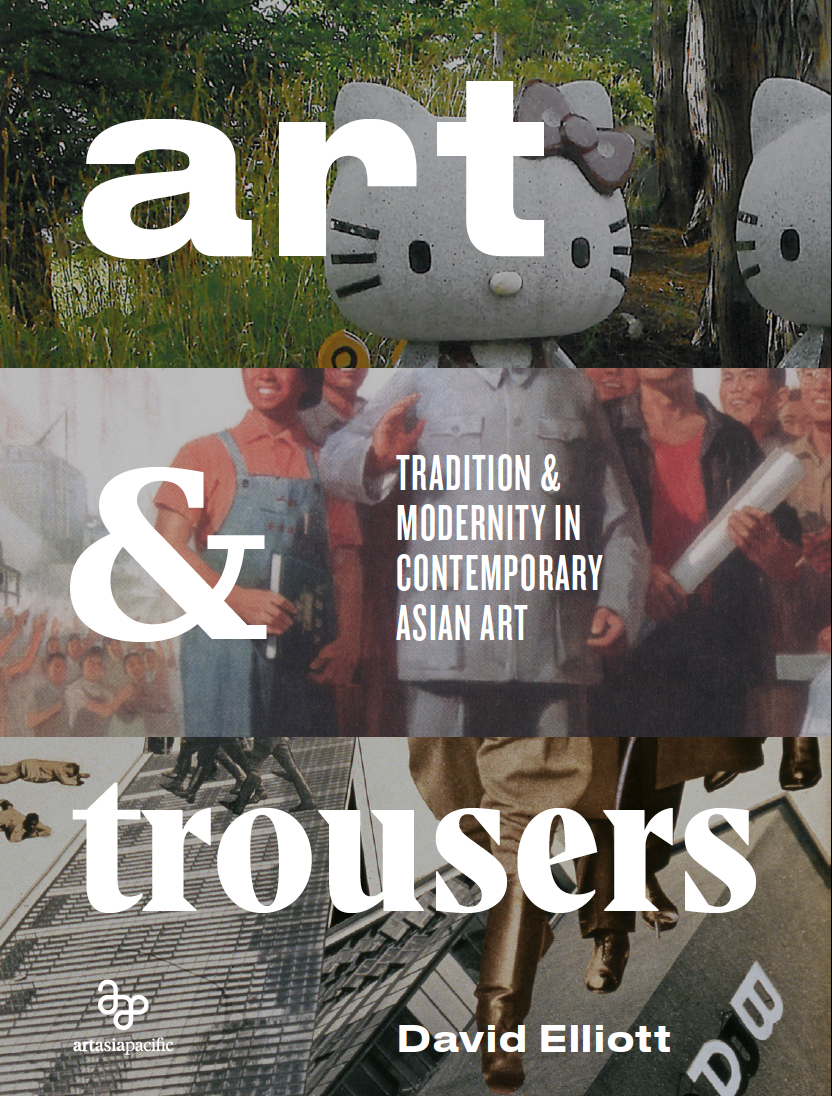

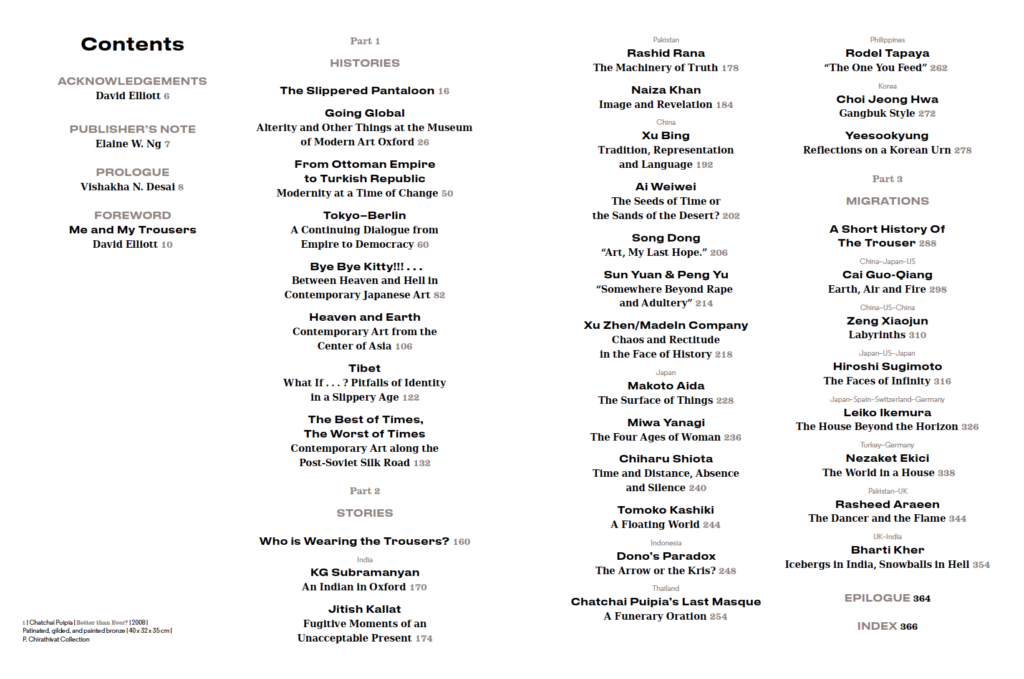

David Elliott, currently Curator at Large for the Redtory Museum of Contemporary Art (RMCA) in Guangzhou, China, adopted a somewhat strange title for his new book. It is Art and Trousers. Elliott, a British-born cultural historian, curator, writer, and educator, studied contemporary history and art history at Durham University and the Courtauld Institute of Art in the UK. As a specialist in modern and contemporary Asian art and Soviet and Russian avant-garde, he has served as the director of the Museum of Modern Art, Oxford; the Museum of Modern Art, Stockholm; the Mori Art Museum; and the Istanbul Museum of Modern Art. Art and Trousers contains essays on “contemporary Asian art” written by Elliott over a period of approximately 30 years, from the late 1980s up to the mid-2010s. The total 33 essays are categorized into three parts: “Histories,” “Stories,” and “Migrations.” As the headings for each of the these three sections suggest, these cover a wide variety of periods and subjects, such as Japan in the Meiji period, the transition era from the Ottoman Empire to the Turkish Republic, the works of the contemporary Japanese artist Makoto Aida or of Rasheed Araeen, who migrated from Pakistan to the UK in the 1960s. Together, they represent a remarkable multiplicity in terms of “history,” “story,” and “migration” concerning art that has developed throughout modern and contemporary Asia. Each section also begins with an introductory essay that, referring to historical, modern, and contemporary art works, outlines the historical significance and symbology of trousers in different cultures; these are not only worth reading as independent scholarly articles on the history of fashion, but also reflect and counterpoint the intricate trajectories of colonization throughout Asia and the uneven power relations between race and gender that run throughout the main essays.

The first part, titled “Histories,” contains seven texts written for exhibitions and art biennales that Elliott has curated. They cover a very wide range of periods and regions, and are all quite dense in content. The first one, “Going Global,” embodies a theme that runs through the entire book, and can be read as a story of the development of Elliott’s own thought on modern and contemporary art since taking the position of director of the Museum of Modern Art, Oxford, at the young age of 27. In the process of researching contemporary Indian art for an exhibition in 1981, he became aware that “with few exceptions, the British art world, and its market, held strong prejudices against any form of modernity that it regards as ‘peripheral,’ particularly when the culture in question is that of a former colony” (p. 30). Also, as he turned his attention to Asia, and deepened his knowledge of postwar Japanese art, Elliott came to the realization that “Japanese art of any kind was regarded ‘peripheral’ and usually ‘derivative’ by the West and omitted from its narrative of modernity” (p. 36). This realization led him to become interested in the presence of “multiple modernities” that exist in various parts of the world. With this awareness of the plurality of modernities and the Western-centeredness in the domain of art and culture in mind, “Tokyo-Berlin: A Continuous Dialogue from Empire to Democracy” is a major survey concerning a largely overlooked mutual influence between Japanese and German art, architecture, literature, and urban planning during the Meiji, Taisho and Showa eras. In “Bye, Bye Kitty!!! Between Heaven and Hell in Contemporary Japanese Art,” on the other hand, Elliott attempts to challenge “the infantilist view of Japanese contemporary culture that more recently has been popular in the West, even amongst some Japanese” (p. 83), a view epitomized by the excessive use of the word “kawaii” [cute].

The second part, “Stories,” includes essays that discuss a total of 18 contemporary artists from various parts of Asia, such as India, Indonesia, Thailand, the Philippines, and Korea: KG Subramanyan (India), Henri Dono (Indonesia), Chatchai Puipia (Thailand), Rodel Tapaya (the Philippines), and Choi Jeong Hwa (Korea), to name only a few. As for Japanese artists, in addition to the aforementioned Makoto Aida, Miwa Yanagi, Chiharu Shiota, Tomoko Kashiki are discussed. Each of these essays was originally written independently as a contribution to an exhibition catalog or a collection of works, but when read as a whole, they illuminate a noteworthy connectivity between Asian modernity, which differs from that of the West, and the impact it has had on the art of the area. The connectivity has been formed by the historical and geopolitical characteristics of different countries and regions in Asia. For example, two essays on world-renowned Chinese artists, Xu Bing and Song Dong, titled “Tradition, Representation and Language” and “Art, My Last Hope” respectively, reveal how, for the artists who began their careers in China around the Cultural Revolution (1966-76) led by the Chinese Communist Party leader Mao Zedong, the political event affected them in establishing their identities as artists. However, it is even more interesting to see how the inescapable effects of the Cultural Revolution manifested themselves in different manners in the artworks of Xu and Song, who are from slightly different generations, and have very different personalities and upbringings. Elliott’s careful analysis draws out both the similarities and differences of their artistic activities.

However, in a highly globalized world, the concept of “nation” – or, to borrow Benedict Anderson’s well-known expression, “imagined community” – is becoming increasingly inadequate as a framework for analyzing the various phenomena surrounding our society. Based on this acknowledgment in the third part, titled “Migrations,” Elliott examines the works and activities of contemporary artists who demonstrate transnational movements across national borders. The seven artists featured in this part – Cai Guo-Qiang, Zeng Xiaojun, Hiroshi Sugimoto, Leiko Ikemura, Nezaket Ekici, Rasheed Araeen, and Bharti Kher – all “for various reasons, […] have migrated to live and work (sometimes temporarily) in different continents and, inevitably, this has affected how they experience and show the world” (p. 296). Araeen, for instance, was born in Pakistan in 1935, and moved to England to escape the closed, suffocating art world there. Yet, in London, where he went in search of an atmosphere of freedom and liberation, Araeen was immediately confronted with the British art world dominated by an exclusive Western-centrism that recognized the art of non-Western countries, including the “Third World” ones, and the works of black artists as merely derivative, inferior. The essay in this book, “The Dancer and the Flame,” describes how, through the publication of academic journals that contain articles on black culture and “Third World” culture, such as Black Phoenix and Third Text, or through the curation of the exhibition “The Other Story,” which first introduced African, Caribbean, and Asian artists of British descent in the UK in 1989, Araeen has resisted “the myopic eurocentrism of Western modernity” (p. 345).

Thus, what Elliott clearly foregrounds in this book are various modalities of “different historical models of modernity that navigate and follow their own paths between tradition and the future” (p. 24), which together describe modern and contemporary Asian art. By exploring varying characteristics in Asian art, and what art historian Reiko Tomii calls “connections” and “resonances” between European and Asian artists in the modern and contemporary eras, Elliott contests the idea that the Western model is the only normative Modernity by demonstrating how multiple modernities have developed throughout Asia. It is obvious that Elliott has carefully composed his essays and introductory text in Art and Trousers, while always consciously acknowledging his own position as “a non-Asian” (p. 13) educated in Europe. Reading this book has made me think deeply about how I, “an Asian (Japanese) person” educated in Europe myself, could propose a view in response to such a work. In other words, David Elliott’s new book, Art and Trousers invites all readers interested or involved in some way with contemporary Asian art, to respond to it from their own different perspectives. In this sense, it requires not a passive absorption of knowledge, but an active participation in an ongoing discussion. As such, in many ways, the book will undoubtedly contribute strongly to the further development of a vigorous discourse on the different faces of contemporary Asian art.

INFORMATION

Art & Trousers: Tradition & Modernity in Contemporary Asian Art

Author: David Elliott

Contributor: Vishakha N. Desai

Published by: Artasiapacific

Date of issue: 2021/9/20

ISBN-10: 0989688534

ISBN-13: 978-0989688536