Film critic and author/editor of numerous publications including Kinokuniya Eiga Sosho 1-3 (Kinokuniya), Michael Cimino Dokuhon (boid) and Československá nová vlna (Kokusho Hankokai). Also translated such books as Peter Bogdanovich’s Who The Hell’s In It (Esquire Japan) and Samuel Fuller’s autobiography (boid) among others, and continues to contribute writings to magazines, movie theater programs, booklets, etc.

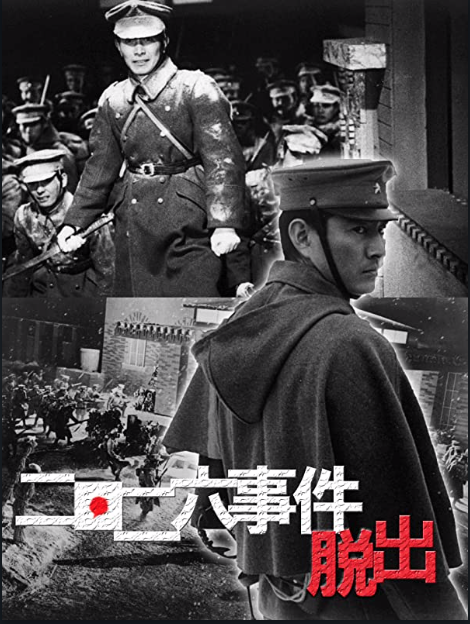

At 5 a.m. on February 26, 1936, some 300 young officers of the Imperial Japanese Army storm the prime minister’s official residence. They kill four policemen, the PM’s brother-in-law, an elderly colonel whom the rebels mistake for the prime minister. Learning that the PM is alive and hiding in a closet in the maids’ room of the residence, Sergeant Komiya of the Kenpeitai (military police), two of his confidants, and the prime minister’s aides band together to start working on a rescue plan.

The Escape tells the story of a famous military coup that is an essential part of the history of Japan’s Showa era (1926-1989). While the characters’ names have been slightly altered from those that appear in history books, it is easy to make out who represents whom. Nonetheless, the film does not advocate for any specific understanding of history or political stance; it’s more of a genre flick (thriller) based on a true story. Lacking a single protagonist, it’s also a kind of ensemble drama, setting it apart from your average genre movie. The story rolls along without focusing on any single group: not the rebellious young officers of the Kodo-ha, not the prime minister’s aides, nor the Kenpeitai.

Without a clear protagonist to serve as a driving force, the story of a movie meant to entertain is prone to lose its ability to proceed in a straight line, and often becomes drawn-out and sluggish or even flat out unconvincing. Remarkably enough, that’s not the case with The Escape, which condenses – or rather daringly simplifies – the complex, interlinked events that took place between the evening before the attempted coup and the end of the incident, into only 90 minutes. That accomplishment is likely due to its almost singular, skillful treatment of, and focus on, the actions of the varied cast of characters. Though the rebel officers actually attacked and seized not only the official and private residences of many leading officials, but also the offices of a newspaper and even the Tokyo Metropolitan Police headquarters, this movie takes place almost entirely in a single location: the prime minister’s official residence. In short, it completely leaves out elements such as the background of the coup and the characters’ psychological and ideological motives in favor of a crisp, efficient, straightforward, and brisk depiction of one event after the other, covering the timeline from the attack on and seizure of the PM’s residence to the eventual escape.

The film is based on the book Tokko: Ni-Ni Roku Jiken Hishi, written by Keisuke Kosaka (on whom Komiya, played by Ken Takakura in the movie, is modeled). An extremely interesting and thought-provoking work, it contains Kosaka’s personal recollections of the events, but the narrative is also punctured by “reflections within recollections” concerning matters related to the attack on the prime minister’s residence that Kosaka himself could not have known about. In these parts, Kosaka, the narrator, obviously becomes the protagonist. In this sense, the original text appears more suited for a popular dramatization. Of course, the true story is in itself as dramatic as the best of movies. The Sergeant Komiya in the film is a type of hero, overcoming one difficulty after the other with his sharp thinking and bold actions, but his heroism is not underlined in any particular way. The actual plan to rescue the prime minister was Kosaka’s invention, but in The Escape it is attributed to a flash of genius by the PM’s aide Hayami (Rentaro Mikuni) – a move made to allocate credit in a more egalitarian manner.

One part in which the film shows its own merits is the climactic escape scene, where the “prime minister” (who is actually Colonel Sugio) is presented to guests coming to express their condolences while the real PM is ferried out of the residence. This scene is so effective because it highlights the “battle against time” better than the original text.

Suspense plays out over two levels, and in this two-level framework, the thrilling passage of time is depicted in several more layers. The sending of an imperial messenger must be prevented before news go out of the prime minister’s survival, so the plan must be carried out in a very limited amount of time. Given these premises, bringing in the condolence callers, having the prime minister escape the residence, and transporting Colonel Sugio’s body outside must all be accomplished in a mere 30 minutes. The tension revolves around whether the prime minister will be able to escape, and then around whether Komiya, his Kenpeitai colleagues, and the two maids still inside will survive. (If 30 minutes pass from the moment the prime minister escapes, his survival will become known to the rebels, putting Komiya and his collaborators within the residence in danger.) As the plan must be carried out with perfect timing, the Kenpeitai men and the prime minister’s aides are depicted all adjusting their watches to the same time before the action, repeatedly asking each other for the time, looking at their watches, and frequently saying “there’s no time.” They are like a group of criminals carrying out an impeccably planned heist. The result is historical fact and therefore known, but the climax makes for a true nail-biter nonetheless.

The approaching time limit is highlighted through the use of clocks. When Komiya and two of the PM’s aides are working on an escape plan, Fukui, one of the aides, keeps knocking on the table in frustration with his inability to come up with any good ideas. This knocking sound overlaps with the sound of a clock counting the seconds, hinting at the growing frustration in the room. In another example, the sentry watching over the body of the “prime minister” (Colonel Sugio) is wearing a Waltham watch. Sergeant Aoyama, Komiya’s subordinate, pretends that his own watch has stopped and uses the opportunity to strike up conversation about the Waltham with the sentry, allowing Komiya to slip into the maids’ room undetected. The sentry relates how older soldiers have forced him to part with high-end watches twice before, but that he’s had no problem replacing them because his father runs a watch shop. Later, when the prime minister, his feet numb after hiding in the closet, is carried behind the sentry’s back with one arm around Komiya’s shoulders and the other around Fukui’s, Aoyama asks this watch dealer’s son for the time again, diverting his attention. This tactic was actually used to distract the sentry, but the part about the watch was probably concocted for the movie. The conversation between Aoyama and the sentry also serves to inform the audience of the time.

Some two years after the release of The Escape, director Tsuneo Kobayashi and screenwriter Hajime Takaiwa teamed up again for Homicide (1964), another film on the February 26 Incident. It was based on the same original text as Shin Saburi’s Hanran (1952), which was probably the first treatment of the incident in cinema. Unlike Hanran, an ensemble drama that depicts the entire coup all the way to the executions of the rebel officers, Homicide shines the spotlight on “Captain Ando” (Koji Tsuruta), a character modeled on Teruzo Ando, depicting mainly that individual’s psychological struggles. Other movies have of course approached these events head on as well, but they are fewer than one might expect. Coup d’etat (1973) depicts the life of Ikki Kita, the intellectual whose ideas inspired the young officers of February 26, but only touches on the coup in an indirect manner, while other films tend to use the events of 1936 mainly as background for melodramatic stories. Efforts to portray the incident itself can be found in one part of the anthology piece Memoir of Japanese Assassinations (1969), as well as in Hideo Gosha’s Four Days of Snow and Blood (1989). While these films appear to sympathize somewhat with the young officers, The Escape sides with the establishment but combines that with a fair portrayal of the rebels’ actions, mainly through the character of a noncommissioned Seki army sergeant (Junkichi Orimoto) who harbors lingering doubts about the prime minister’s death. The suggestion is that the young officers may not all be foolish youngsters; a rare measured approach that adds to the film’s excellence.

Translated by Ilmari Saarinen

INFORMATION

The Escape

Directed by Tsuneo Kobayashi

1962, Japan