Fumiko Nakamura is the curator of Aichi Prefectural Museum of Art in Japan. She explores the relationship between the visual culture, especially the photography, and the contemporary art through exhibitions and research. Recent curatorial exhibitions include Photography will be (Aichi, Japan, 2014) . And she organized “APMoA Project, ARCH” series to nurture the young artists and represented Nobuaki Itoh, Yuki Iiyama, Yoichi Umetsu and Yosuke Bandai. In 2017, she curated the group exhibition Play in the Flow in Chiangmai, Thailand.

The author of this book, Yurie Nagashima, presents herself under several different names, such as “the author,” “Yurie Nagashima” and “I.”

The purpose of the book is to examine how the activities of female photographers, such as those of “Yurie Nagashima,” have been discussed since the 1990s, and subsequently, to review the transition of their expressive styles from “girls’ photographs” to “girlie photographs,” and reinterpret their characteristics within the context of feminism. Therefore, the book was written by an objective and analytical “author,” who addresses the subject “Yurie Nagashima” as if talking about an entirely different person.

Given this odd configuration, one problem that crops up right from the beginning is the question why the person the text is about does not write about herself and her thoughts on the situation surrounding herself at the time from a first-person perspective. Not limited to photographers alone, many artists generally illustrate their own experiences from a first-person point of view. Nagashima, however, chose the third-person position of “the author.”

The reasons for this one can guess from the way Nagashima uses the term “watashi (I, myself)” in the introduction, where she talks about the meaning and motive behind this book. “Watashi” appears occasionally and exceptionally as an individual that speaks out bluntly, as in the following passage.

“My motive for writing this was first and foremost a desire to come to terms with the painful memories of myself and fellow photographers back when we were young, as we unwillingly found ourselves criticized by men (and some women) that were significantly older and had greater social authority. Unable to offer counterarguments at the time, we lost our self‐esteem, and this I want to restore into how it is naturally supposed to be. *1”

From these lines alone one can imagine that there must have been experiences that she was unable to take in sincerely as “watashi.” Whenever Nagashima tried in the past to make a point regarding herself and her experiences in comments starting with “I think,” her statements were flatly turned down as ideas of a girl that made appearances “getting butt naked in front of the camera *2,” seemed to have an “easygoing attitude toward life *3,” and was “physiologically neglecting the outside world *4.” As illustrated in this book, unfortunately all these descriptions around the word “girl” are how other people used to refer to Nagashima and her colleagues.

In other words, the book was an opportunity for the artist, who had never been able to satisfactorily speak as “watashi,” to finally sum up her thoughts under the newly acquired persona of “the author.” This will surely have an encouraging and vitalizing effect on many people, and in this point, the book can be seen as an immensely meaningful publication.

In addition, it introduces a number of views that highlight gaps in research. One of them focuses on the generation of female photographers that perished when the boom of “girls’ photos” took off in the mid ‘90s. Hana Takeda and Michiko Kon had received the Kimura Ihei Award in 1990 and ’91 respectively, but after 1993, Takeda’s and Kon’s work tended to be overshadowed by the increasingly prominent photographic activities of women. However, the fact that everything that has been said about Takeda and Kon was putting unnecessary emphasis on aspects of femininity and immaturity, is one thing that also applies to statements regarding the emerging genre of “girls’ photos,” as the author of this book points out. The enthusiastic discussion of “girls’ photos” reflected the signs of the times and people’s expectations toward the new trend, while the achievements of Takeda and Kon as artists eventually fell into disregard.

Looking back on these developments, one realizes how the historical phenomenon of “the number of female photographers being smaller than that of male photographers” has become a fixed idea of sorts in the appreciation and discussion of photography, and that this might have impeded an active investigation and verbal discussion of the works of female photographers. Written based on a historical point of view, this book highlights once again the necessity to reestablish a discourse on photography.

Furthermore, the main subject of the book are not photographic works as such, but the dimensions of discourse in the realm of photography. Nagashima references numerous documents including books and magazines for her verification of the partiality of arguments, and in the future, a proper discourse on the endeavors of female photographers should certainly be based on the actual works. To prevent a further postponement of an appropriate evaluation of their art, Nagashima, from a creator’s position, entrusts researchers, critics, and the numerous readers of this book with the task of watching and discussing their works.

The crucial point of this book is a conclusion that connects the activities of Nagashima herself and other female photographers to third-wave feminism. In a very convincing way, the author links the activities of female photographers to third-wave feminism that has been using popular culture as a resource for creativity, and zines and other self-made media as platforms for self-expression.

On the other hand, third-wave feminism didn’t come without a whole set of issues of itself. At times, the affirmation of individualism and consumption culture in third-wave feminism tended to be oriented on neoliberalist values (success in market mechanisms based on individual self-responsibility). In addition, amidst the recent upswing of feminism, feminist points regarding the improvement of the status of women, and their free choice of lifestyle, can be very attractive media strategic tools for companies. Once they have been incorporated as tools of capitalism, riot girls are muzzled, so that companies can spread the image of glamorously acting females to suit their books. As a matter of fact, the situation is perhaps not much different from that of female photographers who experienced a “paradoxical kind of suppression in the form of great fuss being made over women *5” in the 1990s.

Nonetheless, I suppose this book was also written with the intention to prevent falling back into the same kind of situation. The book provides some wisdom for astutely reacting and resisting those powers in their aim to conciliate themselves. The position that women are placed in has seemingly become even more complex than in the 1990s, and what Nagashima offers is a viewpoint from which to take a relative look at one’s own situation, and improve it in case one still finds oneself enclosed in an undesired category.

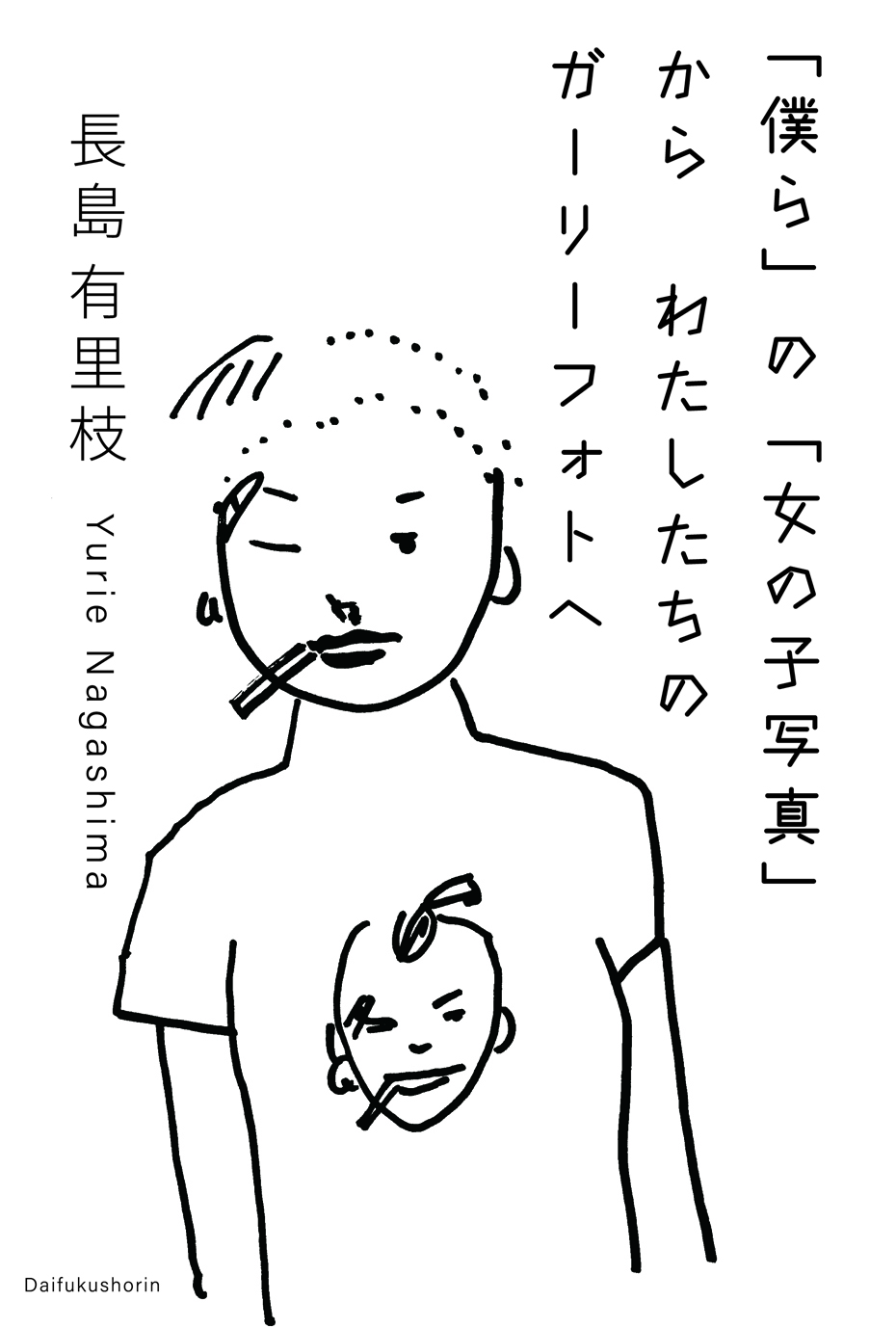

1) Yurie Nagashima “Bokura” no “onna no ko shashin” kara watashitachi no

girlie photo e (Daifuku Shorin, 2020, pp. XI-XII)

2) Focus, June 15, 1994 issue, p.54

3) Kotaro Iizawa “Kanojotachi wa heya ni iru,” in Mito Annual ’99 Private Room II (Art Tower Mito Contemporary Art Gallery, 1999, p.16)

4) Shinya Fujiwara, in Asahi Camera, April 2001 issue (Asahi Shimbun Company, p.85)

5) Michiko Shimamori “Henshu Koki,” in Kokoku Hihyo, June 1998 issue (Madra Publishing, p.140)

INFORMATION

Yurie Nagashima “Bokura” no “onna no ko shashin” kara watashitachi no girlie photo e

Daifuku Shorin

2020