Born in 1987, Yutaro Iijima is a German-to-Japanese literary translator. Having previously worked for a publisher, he is currently a Ph.D. student at Kyoto University’s Graduate School of Letters. His translations include Thomas Bernhard’s Amras (co-translated with Motoi Hatsumi, published by Kawade Shobo).

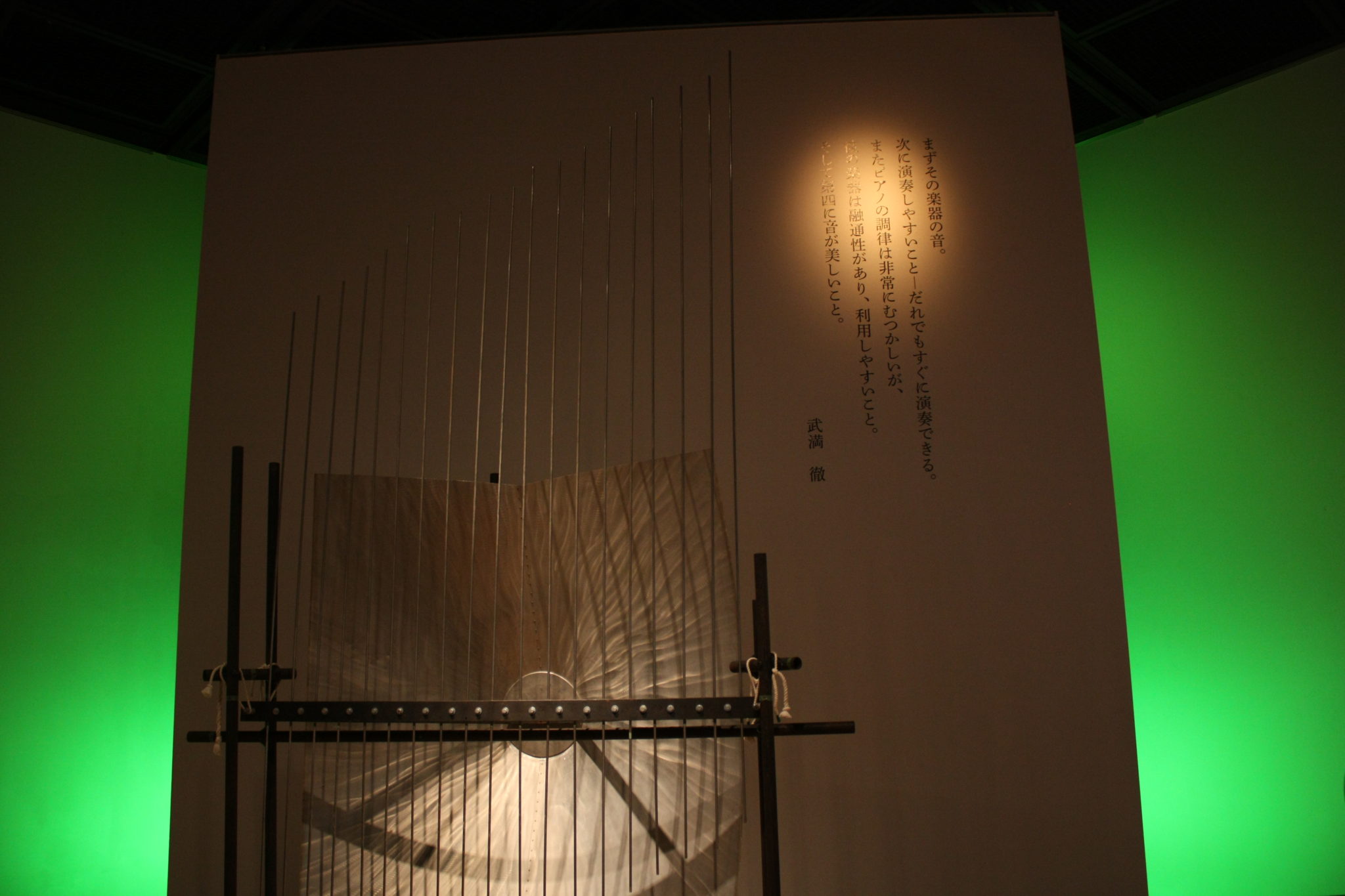

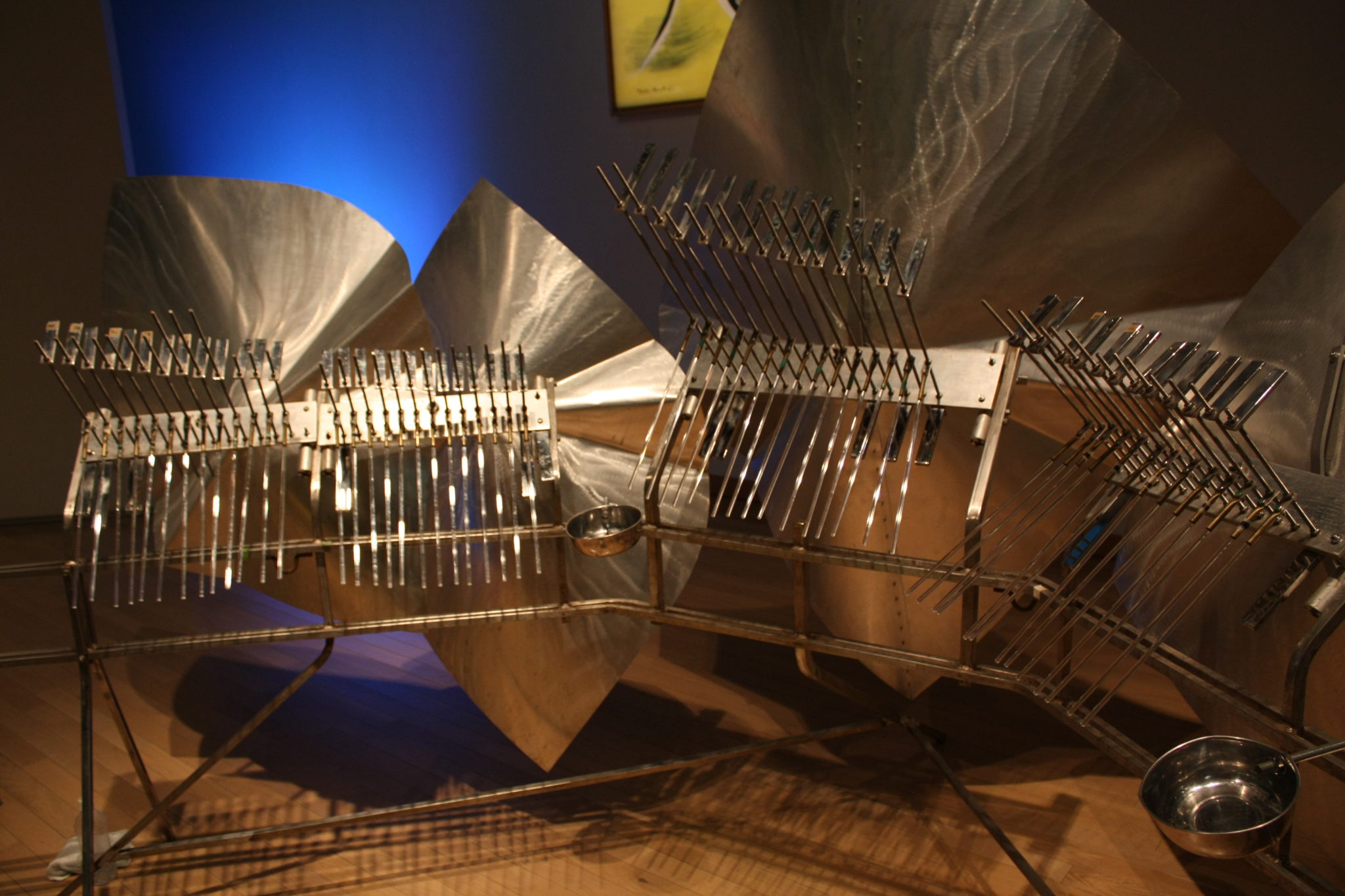

Passing through a birth canal-like corridor lined with displays about the Tower of the Sun, one reaches a fan-shaped gallery full of huge steel objects, each one about two by two meters in size, sitting along the walls of the room. From these extend endless metallic rods in every direction like untrimmed hairs, fitted with rounded metal plates that resemble flower petals. Appearing almost like strange gods of some unknown realm, few who see these objects for the first time would be able to guess that they are in fact musical instruments. But that’s exactly what the Baschet brothers’ “sound sculptures” are. They’re also the highlight of this exhibition at the Taro Okamoto Museum of Art.

I doubt many people will be very familiar with the name Baschet – to be honest, neither was I. I had seen it appear on leaflets and such, but before this exhibition had never had the opportunity to actually engage with the brothers’ works.François and Bernard Baschet participated in the anti-German resistance during World War II. After the war, wanting to do “something beautiful, something pleasurable, something others would enjoy,” they eventually began working together on sculptural musical instruments. Their first creation was a guitar made out of a balloon – a piece already suggestive of the approachable nature of the Baschets’ later oeuvre.

Japanese audiences were first introduced to the Baschets’ art at the Osaka Expo in 1970, where they had been invited by Toru Takemitsu, the producer of the Steel Pavilion Building. François and Bernard spent four months in Osaka, creating 17 sound sculptures over that period. These pieces were rediscovered in 2009 when the Expo’70 Pavilion was opened, and restored to their original splendor. The five sound sculptures displayed at this exhibition are all part of that restored trove.

Having seen the light of day again after 50 years, what, then, are these sound sculptures like? As I mentioned in the introduction, they consist of metal plates and rods. Each of the five artworks has its own unique shape, but they share a humorous quality, as if the scribblings of a child had taken physical shape. As for sound, the sculptures are essentially percussion instruments, though some of them are embedded with a special feature called a Cristal Baschet, which produces sound when stroked with a wet finger. The former give off a bell-like sound, while the latter produce a weightless clang not unlike that of a synthesizer. Both emit impressively lush reverberations. *1

Besides sound and shape, one distinctive feature of the sound sculptures is that they encourage audience participation. The Baschets wanted their artworks to be playable by anyone, would let audience members try them out after concerts, and encouraged exhibition attendees to interact with the sculptures. In fact, the sound sculptures contain no complex technological elements, making it easy for complete amateurs to produce sound. Anyone can compose music with a computer these days, but considering that synthesizers were only just becoming available to the public when the Baschets were active, the fact that their sound sculptures allowed amateurs to create complex soundscapes of their own was surely something revolutionary at the time.

This focus on communication with the audience brings to mind a certain tendency in contemporary art seen from the 1960s onward. Erika Fischer-Lichte calls this the performative turn *2 – the appearance of artworks, across the entire field of contemporary art, that upended the static relationship between performer and audience. One example is Peter Handke’s “Offending the Audience,” first performed in 1966. In this play, the actors do not represent characters of some imaginary world. Instead they hurl insults directly at the audience, doing away with the “fourth wall” between the stage and the audience. Theater and sound sculptures can of course not be lumped together, and the Baschets’ artworks are not provocative like Handke’s play. But by displaying sculptures that could be played and asking the audience to touch them, it can be argued that the Baschets also sought to revolutionize the stagnant form of observing art that people had become used to. In that sense, it’s somewhat unfortunate that this exhibition does not allow visitors to touch the sound sculptures. *3

Of course, that is probably a necessary policy considering the preservation of the artworks. The fact that the sound sculptures are both interactive and unique works of art that require preservation can perhaps be said to illustrate their limitations. *4 All of the Baschet sound sculptures displayed at the exhibition are not only one of a kind, but also historical materials related to the Osaka Expo. History has unfortunately made touching the Baschet pieces something not to be done lightly.

It should be said that the organizers likely anticipated the sort of dissatisfaction I felt not being able to touch the displays. The exhibition also includes Taro Okamoto’s “Temple Bell – Joy,” which is set up so that visitors can try striking it. However, due to the coronavirus pandemic, the ringing of the bell has been put on hold. Come to think of it, it’s highly ironic that the coronavirus crisis has upended this very exhibition, one of themes of which is public participation. We are now discouraged from touching anything without first disinfecting our hands. Touching something, however, is supposed to be a far more human act – the primitive joy of which the Baschets sought to invoke with their sound sculptures. That silent message is one that could be felt in the sculptures’ affectionate shapes, which seem to invite spontaneous touching.

1) A concise explanation of the sound sculptures is available on the museum’s website. You can also search for “Cristal Baschet” on YouTube to enjoy the machines’ enchanting sound.

2) Erika Fischer-Lichte: The Transformative Power of Performance: A New Aesthetics (2008)

3) Music created using the sound sculptures is used as background music at the exhibition, giving visitors a sense of how the artworks sound.

4) The Baschets were also educators who sought to make art accessible to the public. The exhibition pamphlet describes how in the 1980s, the brothers not only created a set of educational instruments known as the Pedagogical Instrumentarium, but also wrote a book on the principles of instruments and designed a kit for people to build their own instruments. This educational work reveals the true aspirations of the Baschets as artists who encouraged public participation.

INFORMATION

The Resonance of Sound and Object – Similarities Between the Sound Sculptures of Baschet and Taro Okamoto

Period :June 2 to July 12 , 2020

Admission : Adult 900yen(720yen), Students and Seniors [65 and over, with ID] 700yen(560yen),

*Children [15 and under] Free

*( ) parenthesis indicate group discount rates

Closed : Mondays(If Monday is a holiday, then next weekday),the day after national holidays