Curator/ CEO NYAW inc./ Co-president of Tokyo Art Acceleration.

After working as a curator at the Tokyo Metropolitan Museum of Photography, 21st Century Museum of Contemporary Art, Kanazawa and Contemporary Art Centre, Art Tower Mito, he became the director of ANB Tokyo and established NYAW Inc. Major exhibitions include ‘Hello World-for the Post-Human Age’ and ‘Resistance of Fog|Fujiko Nakaya’ (Art Tower Mito) and ‘The world began without the human race and it will end without it.’ (National Taiwan Museum of Fine Arts). In addition to planning and consulting on culture/art-related projects such as the art festival ‘Meet Your Art Festival “NEW SOIL”‘ organised by avex, Music Loves Art in Summer Sonic and the Agency for Cultural Affairs’ Cultural Economy Strategy Promotion Project, he also supervises art programmes and features in magazines and on TV. He is also a writer, lecturer, jury member, etc. He was a 2015 overseas trainee for curators from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT) and a part-time lecturer at Waseda University and Tokyo Polytechnic University.

Photo: Ittetsu Matsuoka

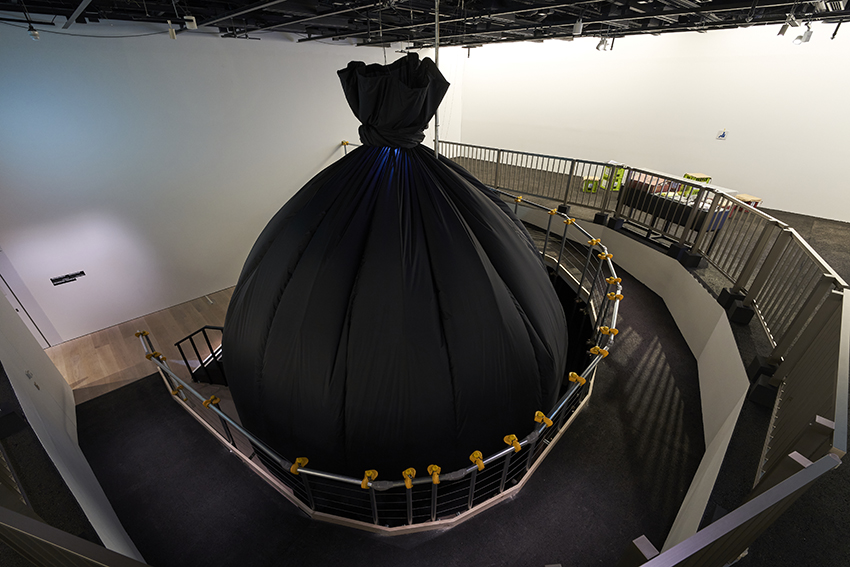

Chim↑Pom

Gold Experience

2012/2022

Installation view: Chim↑Pom: Happy Spring, Mori Art Museum, Tokyo, 2022

Photo: Morita Kenji

Photo courtesy: Mori Art Museum, Tokyo

The end of enemies and a “street” toward the future

Chim↑Pom, with their ironic and humorous (as well as idiosyncratic) way of pinpointing people’s blind spots, have surprised audiences, caused consternation, and sometimes provoked the ire of “adults.” They’ve painted city rats to look like one of Japan’s most recognizable video game characters in “Super Rat,” written the word “Pika” (“flash”) in the sky over Hiroshima, and added a reference to the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster to Taro Okamoto’s giant mural “Myth of Tomorrow” in Shibuya Station. Their parodies of a globally renowned Japanese video game trademark, the trauma of war in the form of the atomic bombing, and Taro Okamoto, a giant of the Japanese art world, have contributed to the group being seen as outlaws who bewilder society and trample on its taboos.

However, being outlaws, their ability to defy what’s considered common sense has allowed them to confront social challenges and the authority of the times head on, inspiring and encouraging young people of their generation whose struggles with the rules and hierarchies of society have left them feeling powerless and frustrated. Chim↑Pom confronting stereotypes and the powers that be in the spirit of the gyaru and yankii types hanging out at Shibuya’s 109 and on Center-gai was unmistakably an iconic image of the Heisei era.

Chim↑Pom from Smappa!Group

SPEECH (from the project “Thank You Celeb Project I’m BOKAN”)

2007

Courtesy: ANOMALY and MUJIN-TO Production, Tokyo

In “Thank You Celeb Project I’m Bokan,” also featured at this exhibition, they organized a charity auction while ironically pointing out the deception inherent in celebrities’ community service efforts. With “KI-AI 100,” they injected energy into the situation of people who, having visited the areas affected by the Great East Japan Earthquake, are overwhelmed by their feeling of helplessness in the face of nature, while in “Don’t Follow the Wind” they set up an art museum in the Fukushima no-go zone, offering a pathway into the emotions of those who lost their homes due to the natural and man-made disaster. While their outstanding ability to sensationalize stands out, the emotional “heat” generated by their actions, which touch on human emotions and local (situational) issues, also inspires the viewer. Chim↑Pom’s ability to propagate their message is one of their greatest strengths.

Chim↑Pom

Build-Burger

2018

Private collection (back)

Installation view: Chim↑Pom: Happy Spring, Mori Art Museum, Tokyo, 2022

Photo: Morita Kenji

Photo courtesy: Mori Art Museum, Tokyo

The standout example of this is “So see you again tomorrow, too?,” held in Kabukicho. After a decision had been made to tear down the half-century-old building housing the Kabukicho District Association, a key player in the neighborhood, Chim↑Pom made the structure a venue for several days of exhibitions, performances, and talks. Notable works here included “Build Burger,” which showcased a combination of the dynamic space of the cut-out building and stacks of the extracted material, cyanotype photography capturing vestiges of the building, and “Libido-Electricity Conversion Machine ‘Erokitel’,” which ran on sexual energy. Meanwhile, the chaotic performance program saw appearances by the likes of musician Seiko Oomori, performing group Crack Iron Albatrosskett, and even Tetsuya Komuro who is most popular Japanese music producer in 90s. With Ellie’s partner and host club supremo Maki Tezuka of Smappa!Group backing everything up as co-organizer, the project made for a grand gathering of Shinjuku residents and people associated with Chim↑Pom, establishing a node in the entertainment district that is Shinjuku’s Kabukicho that functioned as social medium generating a remarkable variety of encounters. Themed on the dynamic of scrap and build, the exhibits included a cyanotype photo of the Kabukicho Renaissance Charter, a document related to the “Kabukicho Cleansing Operation” initiated by former Tokyo governor Shintaro Ishihara. As the document’s inclusion suggests, the Kabukicho project was to define Chim↑Pom’s perspective of standing up against gentrification and, together with the people affected by it, observing the city from a street-level point of view.

Chim↑Pom

A Street

2022

Installation view: Chim↑Pom: Happy Spring, Mori Art Museum, Tokyo, 2022

Photo: Morita Kenji

Photo courtesy: Mori Art Museum, Tokyo

Taken from this perspective, “Happy Spring” at the Mori Art Museum can be positioned as the culmination of Chim↑Pom’s street-level examination of the city and modernity. Symbolic of this was the “Street” project, unveiled at the National Taiwan Museum of Fine Arts as part of the Asian Art Biennale 2017. Its aim was to create a space open to the people, akin to the pedestrianized streets of old, and was used as a venue for a variety of events selected through an open call, inspiring a wealth of little stories uniting individuals with each other. “Street” was displayed at this exhibition, too, in the form of a makeshift piece of asphalt. This could be described as the result of miraculous co-creation between Chim↑Pom, who look at the city and society from the streets, and a real-estate developer that gazes down at the same city from a bird’s-eye point of view.

However, one couldn’t help but feel a slight, or rather quite significant, discrepancy between the “Street” at the National Taiwan Museum of Fine Arts, which was connected to an actual public road, and this version – a lone chunk of asphalt hidden within a skyscraper, accessible only after paying an entrance fee. One would think that the central meaning of “Street” is in its character as a metaphor for a node that connects, with a single line, an art museum – a place of certain authority – with a place open to the homeless and other groups neglected by society (though even streets in the real world are becoming less accommodating to such people). Stowed away on the top floor of a skyscraper – a space symbolizing authority – the artwork’s fate illustrated the roots of the clash of worldviews that came to characterize this exhibition’s run.

Chim↑Pom from Smappa!Group

Street

2017-2018

Courtesy: ANOMALY and MUJIN-TO Production, Tokyo

Installation view: Asian Art Biennial 2017, National Taiwan Museum of Fine Arts, Taichung, 2017-2018

Photo: Maeda Yuki

Said dynamic revealed itself in the issues of “Super Rat” having to be displayed in a different venue and in the name-change problem that arose as a result of Smappa!Group being rejected as a sponsor. First, “Super Rat” is the most important series of Chim↑Pom’s early career. Nonetheless, displayed at the entrance to the exhibition was a new golden version titled “Super Rat Happy Spring,” while Chim↑Pom’s signature “Super Rat (Chibaoka-kun)” (2006) inexplicably came to be exhibited at a project space in Toranomon instead. The decision was rooted in the fact that the artwork parodies an iconic character created by a corporation with offices in the Mori Building, where the museum is located. One imagines that this led to calls for discretion from the Mori Art Museum’s operator. This can be viewed as an act of retaliation for the damage done to said company’s iconic trademark, but from the perspective of art, it’s a serious violation of the sanctity of free expression. On the other hand, however, it must be recognized that art museums are vulnerable in the sense that they cannot operate without their supporters. In this sense, museums are in no way “sacred ground,” but mere organizations bound by the dictates of society that face “death” once they cease to provide benefits and profits to their stakeholders.

This situation is also the root cause of the rejection of Smappa!Group, the operator of multiple host clubs, as exhibition sponsor due to its association with the nightlife business. It is of course impossible to eliminate the chance of prejudice born from superficial understanding that may arise when people see the names of sponsors side by side. One can also understand the decision on the assumed grounds that other sponsors might choose to withdraw as a result, and in terms of Mori’s corporate image that involves being the actor responsible for having “cleaned up” Roppongi, a once infamous neighborhood untouched by gentrification. Nonetheless, Smappa!Group is managed by Maki Tezuka, Ellie’s husband, and the company has long been an important supporter of Chim↑Pom’s projects. In addition, Tezuka’s motto of “hosts as part of society” has seen him organize street-cleaning initiatives with fellow hosts, and in his role as director of the local district association he’s worked on improving public order in Kabukicho. Considering the inclusion of “Street,” a project founded on diversity and equality, one might have expected socially progressive activities such as Tezuka’s to have held more weight.

Given that the two sides had worked together on such a significant project, it isn’t difficult to imagine that repeated discussions were held to avoid a breakdown. However, the result was an announcement that Chim↑Pom would henceforth be known as Chim↑Pom from Smappa!Group. In “Announcement of Name Change,” * the statement detailing the decision, though the group did appear to give consideration to the employees of the museum, the conflict of a “street-level perspective on the city and society” versus a “bird’s-eye view of the city” was made abundantly clear. The sensational news spread like wildfire, and the title of an exhibition held at Anomaly, Chim↑Pom’s home gallery – “Excluded But Not Eliminated, We Are Super Rat” – served to highlight the dichotomy further. On social media, some users decried Chim↑Pom’s tactics as mere viral marketing, but what stood out in the end was the old dynamic of justice for the weak against the big narrative and authority. It’s unfortunate that this buried the message for a new era, the one in which people from different standpoints collaborate to create an open “street” and give shape to countless small narratives born out of relationships between individuals. The question of whether there ever was an “enemy” raises its head.

Chim↑Pom

LOVE IS OVER

2014/2022

Installation view: Chim↑Pom: Happy Spring, Mori Art Museum, Tokyo, 2022

Photo: Morita Kenji

Photo courtesy: Mori Art Museum, Tokyo

It’s true that collections of small stories emphasize the viewpoints and presence of the individuals involved, so while each participant comes away with a high degree of fulfillment, seeing the big picture is more difficult – as is turning it into a topic of public discussion. Developing such stories to a point where they become influential takes time, too. On the other hand, highlighting the main axis of a larger narrative helps to pinpoint the structure of conflict and, from the viewpoint of onlookers peering in from the periphery, makes it easier to get emotionally involved. That’s where the creation of “imaginary enemies” – a classic incitement technique rooted in heroism – comes in. Such methods can certainly still be powerful. However, we have moved from the 20th century, an era dominated by mass media and the state, into the information society of the 21st century, and the Heisei era – with its strong residue of the preceding Showa era – has come to an end. Global capitalism has given birth to economic spheres beyond the state, shaking up traditional power structures, while the potential for social transformations rooted in civic tech has been broadened. The emergence of cryptocurrencies is revolutionizing the concept of money, one of the cornerstones of the state, and inspiring anarchism-like thought.

Against the backdrop of these times, authority – until now the default imaginary enemy – has been weakened, and crude antitheses have also lost their power. In other words, the structure of society is clearly changing. The era of the masses, enveloped in the structure and stereotypes of the average citizen standing up to power and frenzied in their communal illusions, is giving way to an era of people who pioneer their own grassroots understandings of happiness. That’s why “Street” at this exhibition was such an important artwork; it can be seen as an expression of bewildered authorities placing their hopes in those with a “street-level perspective on the city and society.” If that’s the case, actors able to form connections between the street-level and bird’s-eye views while retaining their flesh-and-blood feelings should remain in demand. The crucial question then becomes how both sides should go about breaking free from the conflictual structure. That’s because in the chaotic and fleeting situation we find ourselves in, where things can’t be neatly divided into black and white, the future we’re in for is one in which individuals will need to obtain their own happiness while grasping for things to agree on with other people, no matter how different their respective positions may be.

* “Announcement of Name Change,” posted on Chim↑Pom’s official Twitter feed April 19, 2022.

INFORMATION

Chim↑Pom: Happy Spring

Dates: February 18 to May 29

Venue: Mori Art Museum (Roppongi Hills Mori Tower, 53F) and others