Maki Kaneko is Associate Professor in the Kress Foundation Department of Art History at the University of Kansas, where she teaches modern and contemporary Japanese visual arts and the art of Asian Americans and Asian diaspora. She has published the single-authored book Mirroring the Japanese Empire: The Male Figure in Yoga Painting, 1930-1950 (Brill, 2015) and co-edited “Modern & Contemporary East Asian Art,” special issue, Spencer Museum of Art The Register VIII, no. 5 (2019). Her publications also include: “Contemporary Goshin’ei: The Emperor, Art, and the Anus,” in Noriko Murai, Jeff Kingston and Tina Burrett (eds.), Japan in Heisei Era (1989-2019): Multidisciplinary Perspectives (2022), “Japanese Modern Art History in North America and the Perspective of Asian American Art Studies,” in Megumi Kitahara (ed.), Taniguchi Fumie Studies (Osaka University 2018) and “War Heroes of Modern Japan: Early 1930s War Fever and the Three Brave Bombers,” in Philip K. Hu (ed.), Conflicts of Interest: Art and War in Modern Japan (St. Louis Art Museum, 2016).

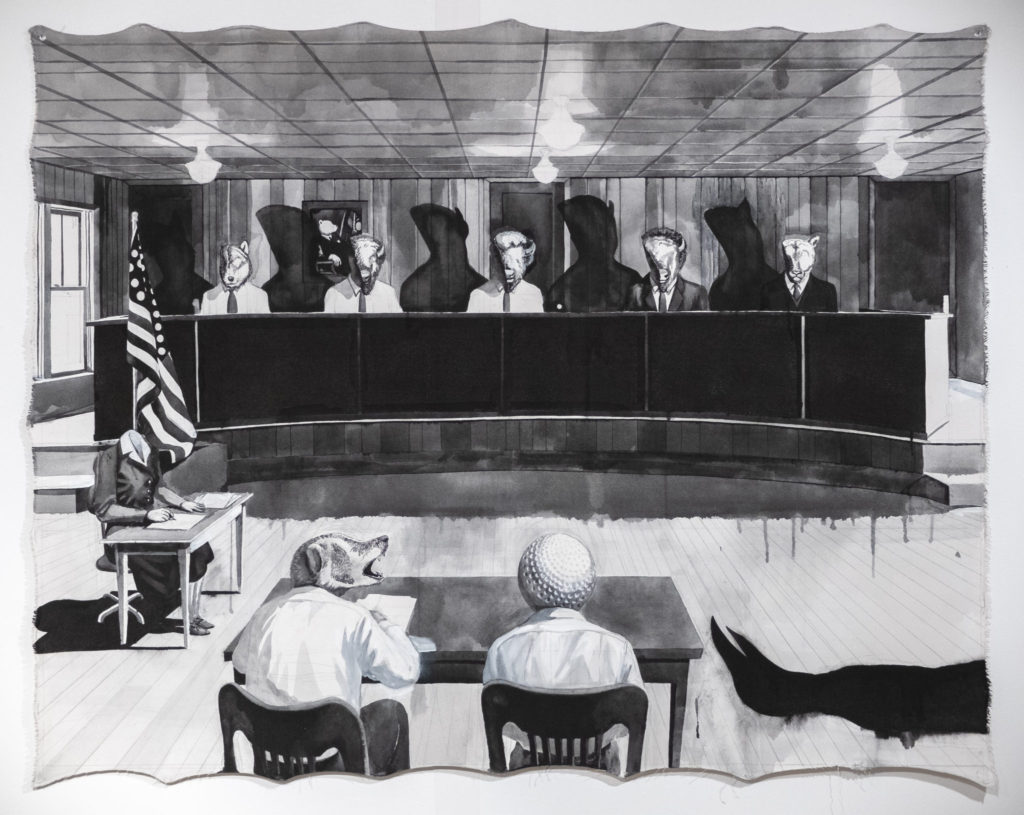

The Protectors(Beautiful Sky Golf Course)2019

Currently on view at the Maruki Gallery, “Warp Drive” is New York-based artist Gaku Tsutaja’s first solo exhibition in Japan and a project that curator Yukinori Okamura wanted to bring to the Gallery “no matter what.” Having moved to the United States in 2006, Tsutaja’s focus since the Great East Japan Earthquake of 2011 has been on creating artworks themed on nuclear power, nuclear weapons, and radiation exposure. Following the completion of a residency program at the Historical Museum at Fort Missoula, Montana in 2019, she has expanded her repertoire of subjects to include the incarceration of Japanese Americans, who were deemed “enemy aliens” during the Pacific War. Tsutaja, who identifies herself as an immigrant, has conducted in-depth field research in both Japan and the U.S., interviewed experts, activists, and hibakusha, and added her sci-fi imagination to this mix to craft stories of nuclear weapons and war unbound by conventional perspectives.

Warp Drive Installation view. Photo by Ali Uchida

For this exhibition, Tsutaja has “warp-driven” artworks previously exhibited throughout the U.S. to the Maruki Gallery. Along with drawings, video works, and props (sculptures) used in her videos created between 2018 and 2021, the main exhibition space features a structure made of scrap lumber that is a reproduction and joining of shacks built in postwar Hiroshima and Nagasaki and the barracks of the Fort Missoula internment camp. The structure is the only new work created for this exhibition, and is designed to allow visitors to view Tsutaja’s art while moving back and forth between its interior and exterior and other exhibition rooms. In doing so, Tsutaja invites viewers on a warp-driven journey through various time-spaces, including those of Hiroshima, Nagasaki, and Fort Missoula, urging a reconsideration and deconstruction of nuclear history and Japanese and U.S. imperialisms from a transnational point of view and, occasionally, a perspective of non-human agency.

Installation view. Photo by Ali Uchida

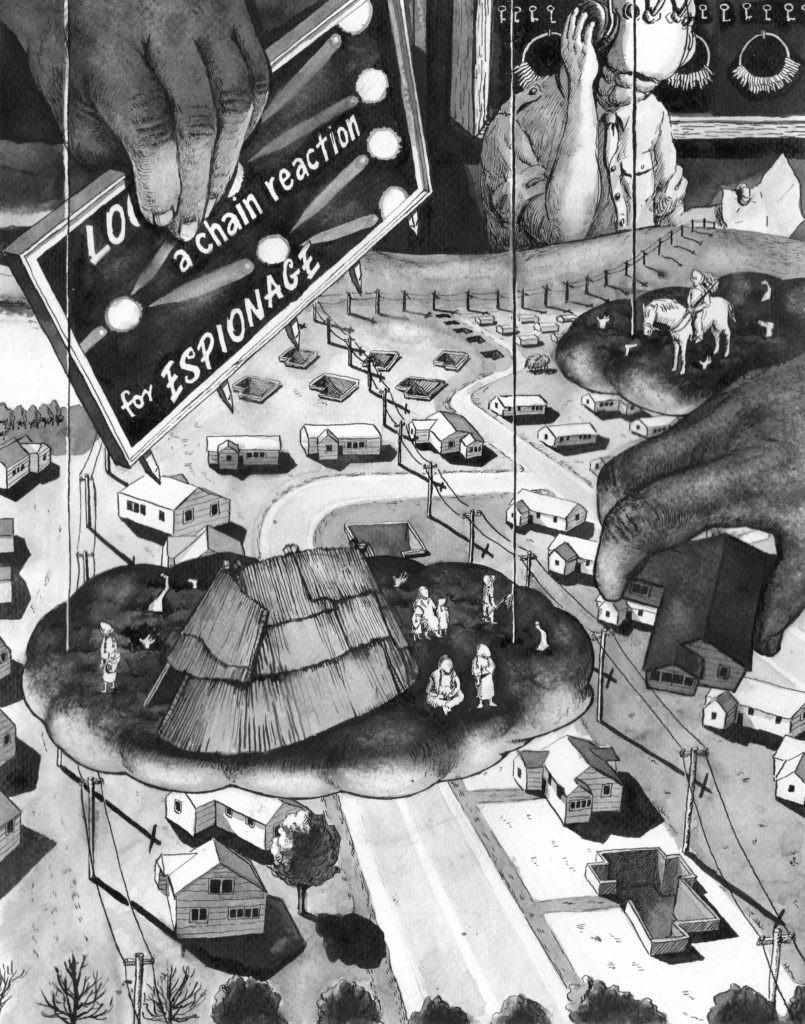

Two large drawings, “The Protectors” and “The Loyalty Hearing,” welcome visitors at the start of the exhibition. These are part of the “Beautiful Sky Golf Course” series, based on research conducted at the Historical Museum at Fort Missoula, and a video work of the same title is also shown at this exhibition. The series was inspired by the surprising anecdote of Issei (first-generation) Japanese Americans who, while being accused of espionage and interned in the Fort Missoula camp, went on to build a golf course on its grounds. “The Protectors” depicts guards holding tear gas guns inside an internment camp, while “The Loyalty Hearing” recreates such a hearing held for Issei Japanese American detainees. In the former work, the tear gas guns are, from the audience’s point of view, pointed both outside and inside the exhibition hall. On the other hand, viewers of “The Loyalty Hearing” are made to stand in the position of observers at the hearing. Who exactly are the “enemy aliens” who should be held at gunpoint? Which side do “we” stand on? In the exhibition’s introductory section, the visitor is being sharply questioned as to where “we” stand in terms of “enemies” and “allies” that were/are divided by the complexities of race and nationality, as well as in terms of the topical issue of immigration.

The Loyalty Hearing (Beautiful Sky Golf Course)2019

Displayed in the next room are 19 drawings from “Daily Drawing,” a series best described as one of Tsutaja’s most significant works to date. For this taxing series, the artist selected 47 stories related to nuclear weapons and released one drawing on social media every day during her exhibition’s run at the Ulterior Gallery in New York in 2020. Its subject matter extends beyond Hiroshima and Nagasaki to include the base of the Manhattan Project in Los Alamos, the Hanford plutonium production site, uranium mines, the nuclear tests at Alamogordo, and the political and economic games that revolve around the production and possession of nuclear weapons. The characters in these stories are replaced by animals, plants, and insects, and historical “facts” and individual narratives are intricately layered with imaginative elements inspired by manga and past artworks, compelling the audience to decipher nuclear history from multiple perspectives. The series takes A-bomb and radiation exposure (both pronounced hibaku in Japanese) and visualizes how their effects transcend the boundaries of nation and ethnicity as well as humans and animals (but are never equally distributed), appearing to present the perspective of “global hibakusha,” a history of nuclear colonialism, and the Anthropocene in which anthropocentrism is causing critical damage to the global ecosystem.

Daily Drawings: Spider’s Thread Day 11:230 Million Dollar Village 2020

Daily Drawings: Spider’s Thread Day 38:Uranium Fever 2020

Proceeding to the large exhibition space in the back, the aforementioned “Hiroshima-Nagasaki-Fort Missoula” barracks appears in a dimly lit room. Screens attached to both walls of the structure play the video works “ENOLA’S HEAD,” a grand chronicle of nuclear history developed from “Daily Drawing,” and the aforementioned “Beautiful Sky Golf Course.” Projected onto the upper part of the back wall is “Study with the Moon,” a unique take on the story of the Enola Gay, who is depicted dreaming and flashing back to scenes from her life while abandoned out in the open at Andrews Air Force Base after the atomic bombing (Tsutaja genders the Enola Gay as female in this particular work). The footage illuminates the barracks like moonlight.

In fact, the original plan for the exhibition was for this room to display a life-size cloth installation of the nose part of the Enola Gay, with “ENOLA’S HEAD” playing inside. However, the war in Ukraine made it difficult to transport the large installation, and the exhibition’s focus was shifted from “ENOLA’S HEAD” to a display dealing with both nuclear history and the internment camps. Tsutaja says she chose the barracks both as a temporary dwelling for a work that lost its “home” due to the war, and as a motif connecting Hiroshima-Nagasaki with the Japanese American concentration camps. However, the shapes and uses of the same type of structure differ significantly between these two cases. Modeled on military housing and built in a relatively sturdy fashion, the barracks for the Japanese American incarceration were used to confine “enemy aliens” and in recent years have been preserved, reproduced , and displayed at numerous facilities in the U.S. as icons of the tragedies. The shacks of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, on the other hand, were built by A-bomb survivors and repatriates as temporary lodgings for survival, and were removed or erased in the course of postwar Japan’s economic development. What emerges here are two “barracks” that are completely different in character, yet both inextricably linked to the politics of war, racial prejudice, and postwar memory. Standing at the intersection of the barracks, which have been fused by bending time and space, visitors can view “ENOLA’S HEAD” and “Beautiful Sky Golf Course” from the back and “Study with the Moon” from between the timbers, as if they were a collage inserted into the structure. This is emblematic of Tsutaja’s approach to art, which employs sci-fi-esque techniques to create collages of multiple time-spaces and perspectives, cutting up conventional history that has been divided across races and nationalities, and even humans, animals, and “things” and recombining it in new ways. In the Maruki Gallery, the intersection and disconnection of these surfaces creates a space that encourages the act of, in the words of Walter Benjamin, “brushing history against the grain.”

Warp Drive Installation view. Photo by Ali Uchida

Finally, make sure to also “warp drive” to the last exhibition room. Displayed there are four works by Iri and Toshi Maruki that transcend the Hiroshima thematic to take up genocide, the Japanese as aggressors, nuclear power, and pollution: “Auschwitz,” “The Rape of Nanking,” “Minamata,” and “Minamata, Nuclear Power, Sanrizuka.” They complement the memories of Asia and Japanese imperialism, which seem to take a back seat in the Tsutaja exhibition, and hint at the possibility of weaving new stories through interplay with Tsutaja’s warp-driven works. Gaku Tsutaja’s first solo exhibition in Japan forms a new warp point in the Maruki Gallery, where a variety of repressed memories beginning with Hiroshima intersect.

Translated by Ilmari Saarinen

INFORMATION

Gaku Tsutaja: Warp Drive

Date: 2022.7.23 - 10.2

Venue: Maruki Gallery For The Hiroshima Panels

Grants from The Asahi Shimbun Foundation

Technical support: Art Tower Mito

Installation support: Hyakujo