Odawara Nodoka is a sculptor, researcher, critic. Born in Miyagi Prefecture, she holds a Doctor of Arts from Tsukuba University. Her exhibitions include Kindai o chōkoku/chōkoku suru Tsunagi and Minamata hen [Overcoming/Sculpting Modernity: Tsunagi and Minamata], a solo exhibition at Tsunagi Art Museum in 2023, and the Aichi Triennale 2019. Solo publications include: “Kindai o chōkoku/chōkoku suru” [Overcoming/Sculpting Modernity] (Kodansha, 2021) and “Monument Theory: Sculpture as an Ideological Challenge” (Seidosya, 2023).

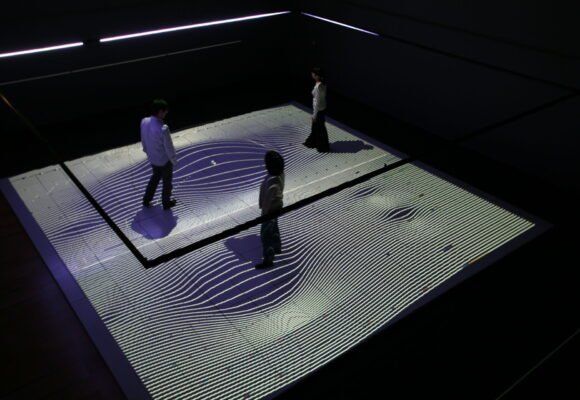

Maya Erin Masuda 《Pour Your Body Out》(2023-2025、YCAM) Photo by Hayato Itakura Courtesy of Yamaguchi Center for Arts and Media [YCAM]

Toxic Queer Bonds: Toxicity and the Other in the Works of Maya Erin Masuda

“Thinking, and feeling, with toxicity invites a recounting of the affectivity and relationality—indeed the bonds—of queerness as it is presently theorized.”

(Mel Y. Chen, “Toxic Animacies, Inanimate Affections,” 2011)

Pipes and baby formula pervade the venue; artificial skin glows under artificial lighting; bouquets of flowers are arranged in yellow, chemically contaminated water. Large windows let in natural light, revealing trees in the courtyard beyond. The windows are open, allowing fresh air to circulate and natural light to pour in. This connection to the outside accentuates the pseudo-ecosystem constructed within the space. Its elements overlap with a wooden framework that crosses the center of the venue diagonally in a work titled “Pour Your Body Out.” Together with two video works, this piece constitutes “scopic measure #17 – Ecologies of Closeness,” a solo exhibition by Maya Erin Masuda.

The liquid formed by dissolving powdered milk distributed by machinery connects multiple elements within the exhibition space. Silently yet critically, it brings into focus the relationship between technology and the “biopolitics” of the state, which regulates life and birth, foregrounding the theme of reproductive rights. Meanwhile, the video work “Plastic Ocean,” composed of countless shots capturing radiation and land, evokes the accident at the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant while reflecting on forms of control, management, and deviation within society in the wake of a nuclear disaster.

Maya Erin Masuda 《Plastic Ocean》 Courtesy of Artist

Nuclear disaster and queer ecology are indispensable perspectives when discussing Masuda’s work. “Pour Your Body Out,” which occupies the majority of this exhibition, was first presented at “Ground Zero,” an exhibition curated by Masuda and held at the Kyoto Art Center in 2023. There, Masuda reframed “ground zero”—typically denoting the site of a nuclear blast or rocket detonation—as “geotrauma” inflicted by humans upon planet Earth, affecting not only people but also forests, land, and animals.

The theory of queer ecology referenced here explores the impact anthropocentric society has had on nature, biology, and sexuality from the perspective of queer theory, which rejects the hegemonic assumptions constructed by heteronormativity and cisgender identity. This theory was applied to the issue of nuclear disasters in Japan by Tomoe Otsuki, who specializes in the study of postwar Japan, popular culture, and nuclear memory. Examining the issue of futurism in Japanese society after the 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake, which caused a severe nuclear accident, Otsuki further expands on the theoretical framework of “Reproductive Futurism,” criticized by queer studies scholar Lee Edelman.

The futurist ideology, premised on the idea of historical progress that views the past and present as perpetually backwards relative to the future, and taking for granted the utopian notion that the future will inevitably be “safer” due to new scientific and technological developments, reinforces and solidifies heteronormativity. It does so by linking the ideal future with the image of children, based on the politics of “a better and safer future, for the children.”

Within this “reproductive futurism” constructed on the premise of heteronormativity (reproduction and procreation), the same social structures are endlessly reproduced under the banner of “the future.” By believing this repetition constitutes “progress,” the possibility of counter-ideologies or queer futures existing outside these norms is stripped away. Otsuki argued for the need to liberate “the future” from the repetition of past and present, raising the possibility of new narratives that encourage imagining queer futures distinct from futurism.

As it was presented in the “Ground Zero” exhibition, “Pour Your Body Out” was supported by a metal framework, drawing attention to the nature of inhumane aspect of institutional systems. In “Ecologies of Closeness,” however, the structure’s material has been changed from metal to wood. The Covid-19 pandemic triggered a surge in lumber prices known as the “wood shock,” which for a time made it extremely difficult to obtain domestic lumber. This shift in material for the exhibition—the construction of the framework from wood, a highly regulated form of life inextricably tied to its market value—implies that control and regulation by means of biopower are not solely a human concern.

Maya Erin Masuda 《Pour Your Body Out》(2023, KYOTO ART SENTER) Courtesy of Artist

Following “Ground Zero,” what Masuda practices in “Ecologies of Closeness” can be described as a redefinition of toxicity. The issue of toxicity in the art establishment was examined by scholar and museum conservator Helene Tello in The Toxic Museum: Berlin and Beyond(Routledge, 2024), in which the author historicizes the use of pesticides in German museum collections from the late nineteenth to the early twentieth century.

Focusing particularly on the Ethnological Museum of Berlin, Tello reconstructs the study of toxicity in museum collections, including the use of insecticides, within the context of nation-state formation, colonialism, the development of the chemical industry, World War I, and the resulting hygiene movement. She reveals that many objects in these collections are highly contaminated, and concludes that the most dangerous and difficult situations arise when contaminated artifacts are returned to their countries of origin.

Issues of contamination and toxicity continue to pose an obstacle in the return of looted cultural properties to their countries of origin, a longstanding challenge facing major European museums. Moreover, a dual toxicity emerges here: “toxicity that is matetrial, or symbolic.” In other words, within museums there exists a material toxicity—the residual chemicals from past conservation treatments—which complicates efforts toward decolonization and the return of stolen artifacts. Simultaneously, monuments and statues remaining in public spaces and museums continue to harbor a political and symbolic toxicity through their association with colonialism, dictatorship, and war. Through these considerations, The Toxic Museumdemonstrates that the institution of the museum is never neutral, but rather a political space that contains an inherent toxicity.

I interpreted “Ecologies of Closeness” as an attempt to subvert the museum as a politically toxic space and instead display its problematic framework by way of visual art. Notably, the exhibition appears positioned as an opportunity to reconsider the affectivity and relationality of queerness as currently theorized—and the bonds these elements foster—by prompting reflection on and experience of toxicity. This orientation is evident in the citation of “Toxic Animacies, Inanimate Affections,” a research paper by queer theory, animal studies, and critical race theory specialist Mel Y. Chen, in Masuda’s video work “All Small Fragments of You,” which is also part of the exhibition.

Chen’s paper explores how queering and racializing non-human materials leads to animacy. It reexamines how the linguistic, cognitive, and sensory distinction of animacy (animate/inanimate) is in fact fluid, political, and emotional. Particularly through the mediation of toxicity (in which poison equals a chemical/harmful substance), the connections between life and non-life, objects and humans, and emotion and matter are reconfigured. Animacy goes beyond issues of personification, being built on the recognition that abstract concepts, inanimate objects, and things in between can be queered and racialized without human bodies present. Mel Y. Chen’s position is that theorizing animacy offers an alternative or complement to existing biopolitical and recent queer-theoretical debates about life and death.

Maya Erin Masuda 《All Small Fragments of You》 Courtesy of Artist

The “toxic queer bonds” theorized here form the underlying theme of “All Small Fragments of You.” The work consists of narration by Maya Erin Masuda, scenes of communal living with an intimate other, sculptures in a museum, and multiple texts. “Plastic Ocean” and “All Small Fragments of You” are two strikingly contrasting video works. While the former evokes continuity with the “Ground Zero” exhibition, presenting fragments of post-nuclear disaster landscapes detached from human life, the latter powerfully conveys the spontaneous presence of life and matter—intimacy, the dampness of sweat, sunlight dappling through leaves, the caress of wind, and scent.

The artist’s voice overlaps here, speaking to the viewer. Pointing to three medicines—a drug to to escape gender normativity, a drug to stop menstruation, and intestinal medication—accepting them, and gazing upon “her” who with these medicines seeks to transform into a body neither female nor male and attain “freedom”; this is where the work begins, and where it ends. “We are shaped by absorbing all molecular otherness,” Masuda declares. The implication of “we” here extends beyond bodies and politics. It encompasses land, abstract concepts, inanimate objects, and everything in between. The gaze directed at “all queers living amidst tenderness and suffering, all things queered and reclaimed”—as listed in the acknowledgments—sustains the exhibition. It therefore stands as a testament to steadfast resistance.

References:

Tomoe Otsuki, “Kakusaigai go no ‘mirai’ no hyosho to kodomo kyuseishu: Fukushima ni arawareta ‘Sun Child’ zo wo saiko suru,” Sculpture 2, Shoshitsukumo, 2022.

Helene Tello, The Toxic Museum Berlin and Beyond, Routledge, 2024.

Mel Y. Chen, “Toxic Animacies, Inanimate Affections,” 2011.

Lee Edelman, No Future: Queer Theory and the Death Drive, Duke University

Translated by Ilmari Saarinen

INFORMATION

Maya Erin Masuda "Ecologies of Closeness"

scopic measure #17

Maya Erin Masuda

Ecologies of Closeness

Duration: July 5th. 2025 - November 2nd

Venue: Yamaguchi Center for Arts and Media [YCAM]