Researcher on post-war Japanese avant-garde art and curator of Fuchu Art Museum. Received MA in art from the Tokyo University of the arts. Based on researches of artworks and documents、has written a history of post-war Japanese avant-garde art through curating exhibitions and writing essays.

Exhibitions include Jiro Takamatsu; Universe of his Thought(2004), At/From Tamagawa 1964-2009(2009)、Kaku-Co; O JUN 1982-2013(2013). Writings are Drawing Seen As a Pssibility, in “Jiro TakamatsuAll Drawings”(2009), Return after 20 Years, in “Reflection: In Return to Koji Enokura”(2015), “Noe Aoki : Nagare no naka ni Hikari no Katamari”(2019). Co-edited an anthology “Reading Jiro Takamatsu”(2014).

Minoru Yoshida (1935-2010) was a latter-period member of the Gutai group that was founded by avant-garde artists in the Kansai area. He has been noted especially for the hard edge paintings and futuristic sculptures incorporating acrylic and motors that he made in the second half of the 1960s, before shifting the focus of his work to the performance format in the ‘70s. On three consecutive rainy days in June 2019, films documenting his time in New York, where it all started for Yoshida, were shown for the first time in Tokyo. The program contained videos capturing a total of seven performances staged between 1974 and 1976, and a studio video recording.

Courtesy of Midori Yoshida & Ulterior Gallery, NY

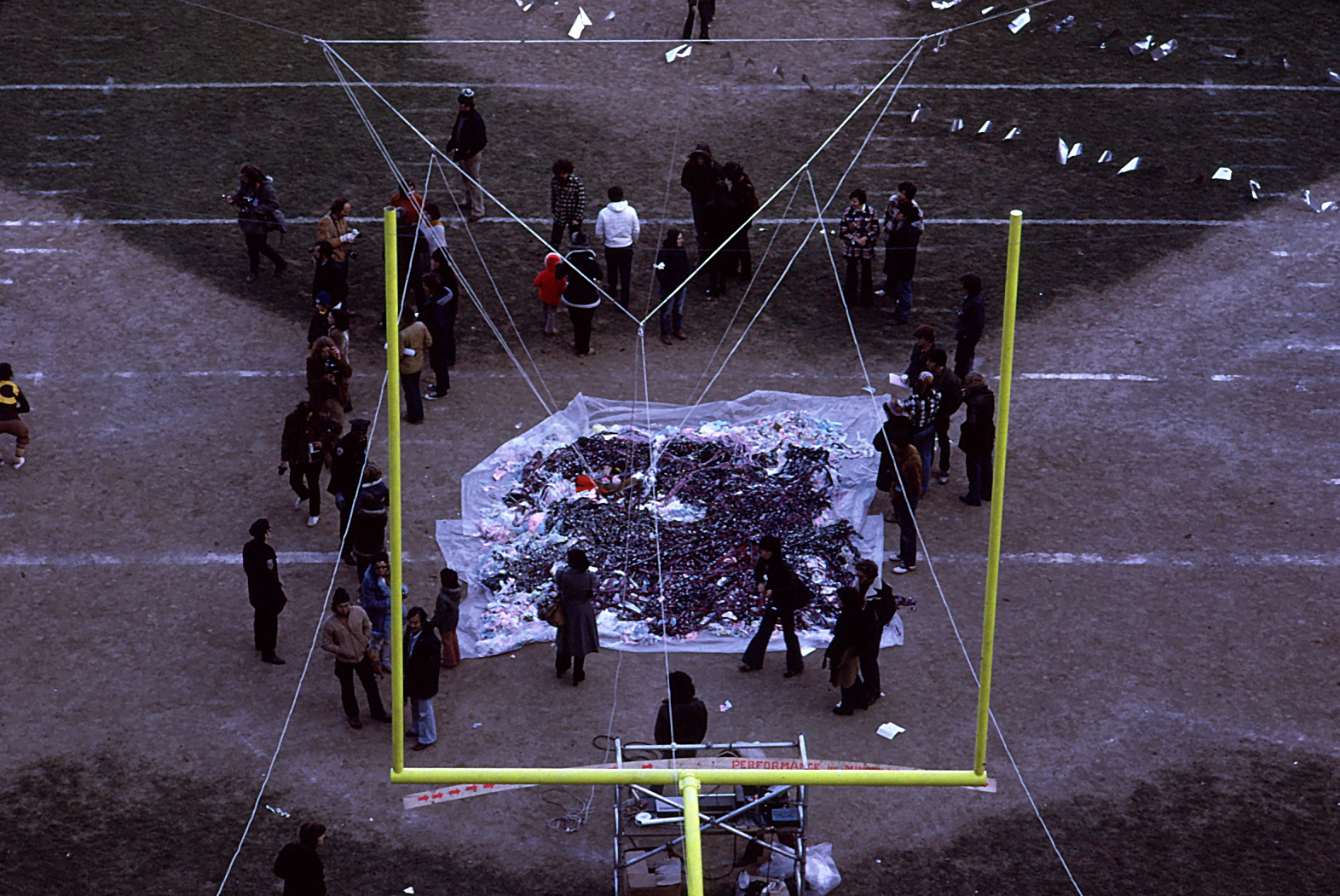

In “The Theory of New Relativity; Featuring Synthesizer Jacket #2,” a performance realized at the 11th Avant Garde Festival of New York curated by Charlotte Moorman in November 1974, Yoshida uses a long rope that is hanging down from above in the middle of an athletic field, to suspend his body in the air while using his feet to push off from the ground. Taking advantage of the rope’s physical reaction, he jumps higher and higher, and tries to remain as long as possible floating in the air. All this is captured in a black-and-white video (which has been digitally transferred for screening).

Yoshida is wearing a somewhat futuristic looking outfit including tights, long boots, and his self-made synthesizer jacket. On the ground is a pile of cushioning material (probably pieces of cloth), above which – depending on the camera angle – the floating Yoshida sometimes looks like an astronaut landing on the moon. Metal plates arranged in regular intervals on the ground reflect the sunlight as if to establish a communication line to outer space.

In reality, gravity is of course taking effect, so Yoshida’s body is mercilessly pulled back to the ground. His attempts to defy gravity through human power and his device in hand are metaphorical representations of the advance of mankind into outer space as symbolized by the moon landing of Apollo 11 five years earlier in 1969; aspirations toward scientific and technological developments, along with the aspect of irrationality this comes with; and the alienation that Yoshida himself experienced after moving to the USA.

From the reactions of the surrounding crowd that witnessed Yoshida’s performances, one could understand the psychological effects that Yoshida’s extraordinary challenges had on those around him. It was a chain of repeated trial-and-error, revolving around a body that kept jumping up only to be pulled down again. As a result, in these persistently performed actions that resembled ascetic practices of sorts, some kind of communication was generated between Yoshida and his amazed – and sometimes cheering – audience.

The element that supported Yoshida’s communication is a monotonous electronic sound generated with his synthesizer jacket. Yoshida used this synthesizer he had built from a streamline-shaped acrylic panel in all of the eight videos that were shown this time.

Courtesy of Midori Yoshida & Ulterior Gallery, NY

Electronic equipment and acrylic cut into organic shapes had already appeared in the late 1960s when Yoshida was a member of Gutai, filling spaces with “environmental art” featuring moving acrylic parts driven by motors, and reflections or transmissions of light or water. One representative example of this is “Bisexual Flower,” which was shown at the Osaka World Expo 1970. If we consider such practice as part of a greater scheme designed to eliminate the boundaries between works and audiences in happenings staged with the help of advanced technology, the developments from there surely make sense.

The performances in 1975 and ’76 took place on streets and beaches, with direct communication through language and dialogue thrown in as an additional element. His native language that was developed on the foundation of kanji characters as “loan words,” and the (un)translatability thereof, replaced technology as a subject matter in Yoshida’s work. Regarding the part where he reads one kanji character each in Japanese and English in the 1976 performance “Absolute Landscape #3 (Psychic Revolution); Featuring Synthesizer Jacket #2” for example, Nina Horisaki-Cristens pointed out that Yoshida intentionally caused mistranslations by removing parts of hiragana or katakana characters. (Nina Horisaki-Cristens, When Video Promised a Sci-Fi Future, in “artasiapasific” issue 112, Mar/Apr 2019, pp.73-76)

Yoshida humorously illustrated his own position as an immigrant on the fringes of different cultures by skillfully overlapping a story set in a future age of extraterrestrial visitors. Who is the real alien – the man from outer space, or the earthling? While separating him from his environment, the transparent helmet that Yoshida wears on his head is at the same time separating the environment from the artist. Through the transparent cover, however, Yoshida could see the other, and even if the sound may be distorted, he could certainly speak as well. In this age of progressing globalization, the elements of clashing cultures and a desire for communication that are presented here compel with an increased sense of reality.

As an international epicenter of art after the war, New York attracted numerous artists. Minoru Yoshida added a layer of bright color to the amassed struggles of such Japanese artists as Yayoi Kusama, who singlehandedly challenged the value system centering around white males. It is deeply gratifying that it was a Japanese gallerist in New York, to whom we owe the opportunity to see these historical documents of Minoru Yoshida in Tokyo today. The venue, Space 23℃, is a gallery that was set up in the former atelier of Koji Enokura after his sudden passing. Assiduously exhibiting Enokura’s works and related documents since its opening in 2000, the gallery has been steadily communicating Enokura’s out-of-the-box attitude as an artist who was often placed within the context of the so-called “Mono-ha” movement. Also in the case of Minoru Yoshida, I think it is integral to look not only at his reputed contributions to Gutai, but scrupulously examine his ideas as expressed also in his later performances, and his activities that connect the time before and after his American years. In this sense, these video screenings certainly make a significant contribution.

Photo : Seiji Kakizaki / Courtesy of Midori Yoshida & Ulterior Gallery, NY

INFORMATION

Minoru Yoshida Performances in New York

Ulterior Gallery at Space 23℃ in Tokyo

2019.6.14-16