Editor, born 1980 in Hokkaido. Worked as an editor for Shotenkenchiku and Pen, before starting to work freelance in 2017. Has been in charge of editing and writing articles mainly on architecture, design, art, for magazines including Pen, Casa BRUTUS, ELLE DÉCOR JAPON, Harper’s BAZAAR, and madame FIGARO japon. Is also involved in the planning of exhibitions, the creation of exhibition catalogues, and the production/organization of corporate exhibitions and catalogues.

Akira Fujimoto “2021 #TOKYO2021” 2019 © TOKYO 2021 Executive Committee Photo: Mitsuhisa Mitsuya

For us living in Japan today, what is the point up to which we are envisioning the future? In Tokyo, there are all kinds of matters going on in recent years that share the upcoming 2020 Olympic & Paralympic Games as a common goal, however for all of us, life will of course go on even after the end of the Games. “TOKYO 2021” is the name of an exhibition project that looks at how we imagine Tokyo in the year after the Olympic & Paralympic Games.

Staged on the first floor of the TODA CORPORATION building in the vicinity of Tokyo Station, “TOKYO 2021” combined two successive exhibitions themed on architecture and fine art respectively. The old Toda Kensetsu building is going to be torn down in order to erect a new company building, and next to providing the venue, the company supported of course also the exhibition as such. The event at large was organized by artist Akira Fujimoto and architect Yuko Nagayama, whereas architects Hideyuki Nakayama and Ryuji Fujimura curated the architecture exhibition, and artist/critic Yohei Kurose took charge of the curation of the art exhibition.

Akira Fujimoto “#New National Studium Japan” 2016/ Tokyo © TOKYO 2021 Executive Committee Photo: Takamitsu Miyagawa

The exhibition originated from organizer Akira Fujimoto’s own art project “2021.” As soon as Tokyo was chosen to host the Olympic & Paralympic Games in 2020, Fujimoto installed a giant wooden object in the form of the number “2021” right in front of the planned construction site of the new National Stadium. This was the initial occasion that inspired Fujimoto to continue to take the same object to place across Japan. While regarding the Olympic & Paralympic Games as an opportunity for redefining Tokyo as a city, Fujimoto sees it at once as an occasion for asking himself what the years after 2020 may have in store.

Held prior to the art exhibition, the architecture exhibition was directed by architect Hideyuki Nakayama. He invited architecture students and members of society with architecture related professions to participate, and eventually gave the participants assignments to work on. In addition to displays of the works they came up with as a result, the exhibition showcased also processes and discussions as to how to tackle their respective assignments. For the concrete assignments themed around a reconsideration of the city of Tokyo, Nakayama asked architect Ryuji Fujimura for help. They eventually invited 13 architects to get involved and assist the participants with their assignments.

In his position as the exhibition’s director, Nakayama’s idea was to create an opportunity for reflecting on the city within a greater time frame, and from a broader perspective. Working as an architect and at once also teaching at the Tokyo University of the Arts, Nakayama pointed out that students’ graduation works in recent years increasingly included reproductions of urban areas dominated by share houses or closed-down shops. Not only for the students today, but even back when Nakayama was a student himself, the massive sense of scale that characterized the plans of architects like Kenzo Tange, who were involved in urban renovation activities after the war, was something that seemed quite far-out and disconnected. However, their idea must have been that a situation in which it was difficult to approach their work with a future vision of the city, was all the more an opportunity for breaking out in this respect.

Having been appointed by Nakayama, Fujimura came up with his idea for “Tokyo 2021” (using the Chinese character for “island” instead of that for “east” for the “to” in Tokyo), for which he assigned participants with the conception of development plans for a timber yard in Shinkiba, Koto-ku, that was supposedly to be redeveloped as a 1km2 large artificial ground. Fujimura looks back on the development of Tokyo while referring to the development of urban planning in post-war Japan. According to his view, Tokyo used to aim to become a government-administered “multi-core city” up to the 1990s, but upon entering the 2000s, the focus shifted toward a renewal of the city through large-scale projects devised by urban developers. In the process, areas like Otemachi, Nihonbashi, Kyobashi, Ginza, Roppongi, Shibuya and Shinagawa each built their own distinctive image, and the competition between them gained momentum. Based on such kind of development, Fujimura interpreted Tokyo as an “aggregation of small islands,” and formulated the question how the city may be envisioned after 2021.

Architecture exhibition theme “Tokyo 2021” © TOKYO 2021 Executive Committee Photo: Takamitsu Miyagawa

However the answers the participants came up with after a workshop of several weeks incidentally highlighted the difficulty of painting a future picture of a contemporary Japanese city. Participants were divided into four groups based on different viewpoints, and presented their suggestions from the respective points of view in the form of interim reports. Following was a discussion involving also Nakayama, Fujimura and the 13 architects, which was concluded with a summary of the advantages of each group’s suggestions. What was eventually presented in the final meeting was merely a mediocre compromise with an undeniable sense of déjà vu.

According to the proposal worked out by the participants, the 1km2 large artificial ground was to be divided into a large and a smaller portion. The plan revolved around facilities related to timber research – in reference to the context of the former timber yard and the Shinkiba area at large – in one part, and office buildings, a convention center, hotels and a sandy beach, and in addition, a town made up of apartment complexes for immigrants in the other. The image of the city that was presented here looked very much like a commerce and business oriented plan worked out by urban developers rather than architects, and was somewhat reminiscent of the Daiba area. Fujimura refers to the discontinuance of world city expos as something that marks the demise of 20th century style urban development, and in this sense, the fact that they came up with a town resembling Daiba, a place that is exactly a product of that, has something ironic to it. Add to this the thoughtless idea of tackling issues as highly sensitive as that of immigrants by dividing territories by descent.

I suppose that both Nakayama and Fujimura didn’t really approve the image of the city that the participants presented. Besides this, there is a fundamental problem also in the fact that one cannot simply call their exhibition a failed project. As Nakayama and Fujimura have previously pointed out, one can conclude that the exhibition stressed once again of the difficulty of drawing up visions of contemporary Japanese cities by way of assignments. The project combined an architecture exhibition and a subsequently held art exhibition, whereas these two exhibitions were not directly related. This makes me wonder whether considering connections between architecture and art when discussing the future of the Japanese city wasn’t an option for the architecture exhibition. I guess I don’t need to mention concrete examples of other major cities around the world in which using art as a dynamo for reconstruction projects isn’t uncommon. Meanwhile in Shibuya, where redevelopment is currently in full swing, and the area is undergoing a huge revamp, it’s basically all about office space and business, which in my view only highlights the miserableness of a town without a single art museum. The art exhibition featured many works that focused on the city and the views of those living in it. It appears to me that an exchange of views between both exhibitions might have resulted in a different kind of proposal.

Architecture exhibition theme “Tokyo 2021” © TOKYO 2021 Executive Committee Photo: Takamitsu Miyagawa

Fujimoto’s idea behind “2021” was supposedly to discuss what the increasingly shrinking Japanese society could possibly do after the Olympic & Paralympic Games in Tokyo 2020. What kind of future could be envisioned for this country that is exhausted as various issues keep piling up? Is the trivialization of the task of urban development a problem that has to be blamed on the participants alone? If we don’t do anything to change this social background, there is no way for us to envision any kind of future for a place that is already ridiculed as being an underdeveloped country. The question is what kind of future picture we come up with for our city, now that we have become aware of the situation. In this respect, the exhibition can be seen as a signal for taking our marks.

Architecture exhibition theme “Tokyo 2021” © TOKYO 2021 Executive Committee Photo: Takamitsu Miyagawa

The curator of the art exhibition was artists/critic Yohei Kurose. Having detected recurrences of “calamities and festivities” within Japanese history, Kurose chose “un/real engine” as the exhibition’s title. He argues that recurring calamities and festivities have inspired new imagination in the realm of culture, and new technologies in the realm of science, and a great number of artists have been partaking in festive activities following disastrous events. The 1974 Tokyo Olympics were preceded by World War II and the atomic bombings, and prior to the Games in Tokyo in 2020 we had the Great East Japan Earthquake. Artists and architects alike have been involved in the implementation of festivals as occasions to help overcome the consequences of disasters, and forms of commemoration are scientifically and technologically updated in response to the forms of disasters. The exhibition focused on the part where this perspective overlaps with the history of contemporary art in Japan.

Kurose presents the genealogy of Japanese contemporary art from the 1970s, an era that marked the advent of the information society, up to the present day, and discusses how memories of all kinds of disasters are being addressed through the creation of art that incorporates the culture and technology of its time. Next to Fujiko Nakaya’s “Friends of Minamata Victims – video diary,” a work documenting a protest campaign of Minamata patients, and Kazuhiko Hachiya’s “Seeing is believing,” a display of comments from people immediately after the Great Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake on an electric signboard that required a special viewing device to be read, Kurose showed in this exhibition also works by Norimizu Ameya, who has been dealing with the Aum Shinrikyo incident; Naohiro Ukawa, whose focus has been on disasters even before the Great East Japan Earthquake; and Makoto Aida, whose previous work dealt with the Great East Japan Earthquake and subsequent nuclear accident.

Hidenori Watanabe “ ‘We Shall Never Forget’: Last Movements of Tsunami Disaster Victims” © TOKYO 2021 Executive Committee Photo: Mitsuhisa Mitsuya

There were also works that exceeded the realm of art so to speak, such as engineer Hidenori Watanabe’s “‘We Shall Never Forget’: Last Movements of Tsunami Disaster Victims.” This work documents on a map the evacuation efforts of people who lost their lives in Iwate after the Great East Japan Earthquake, from the moment of the earthquake until the arrival of the tsunami. With the consent of the surviving families, the work traces through moving lines the locomotion of these people, whose names are indicated with Roman letters, to make the viewer hear the silent voices of the victims. These contributions that can indeed be considered to be representing a form of “memorial engineering” gave visitors an opportunity for reconsidering the contemporary history of Japan. Based on his multilateral viewpoint and analysis, Kurose created an exquisite tapestry by interweaving festivities and memorial services as a vertical, and Japanese contemporary history as a horizontal axis.

Kazuki Umezawa “Summer clouds” 2019 © TOKYO 2021 Executive Committee Photo: Mitsuhisa Mitsuya

For the displays of these works, Kurose divided the venue into two areas. Exhibited at “SiteA: Saigai no kuni (land of disasters),” a space themed around disasters and memorial services, were Kazuki Umezawa’s “Summer clouds,” an apocalyptic scenery collaged around a flash of light reminiscent of a mushroom cloud; Chaos Lounge’s “Tokaido gojusan doji junrei-zu,” which reverses east and west in “The Fifty-Three Stations of the Tokaido” to make Kyoto Animation the final station; and Yutaka Umeda’s “53 stages,” 53 cushions filled with earth collected at those 53 stations, and arranged on the floor to point in the direction of Kyoto.

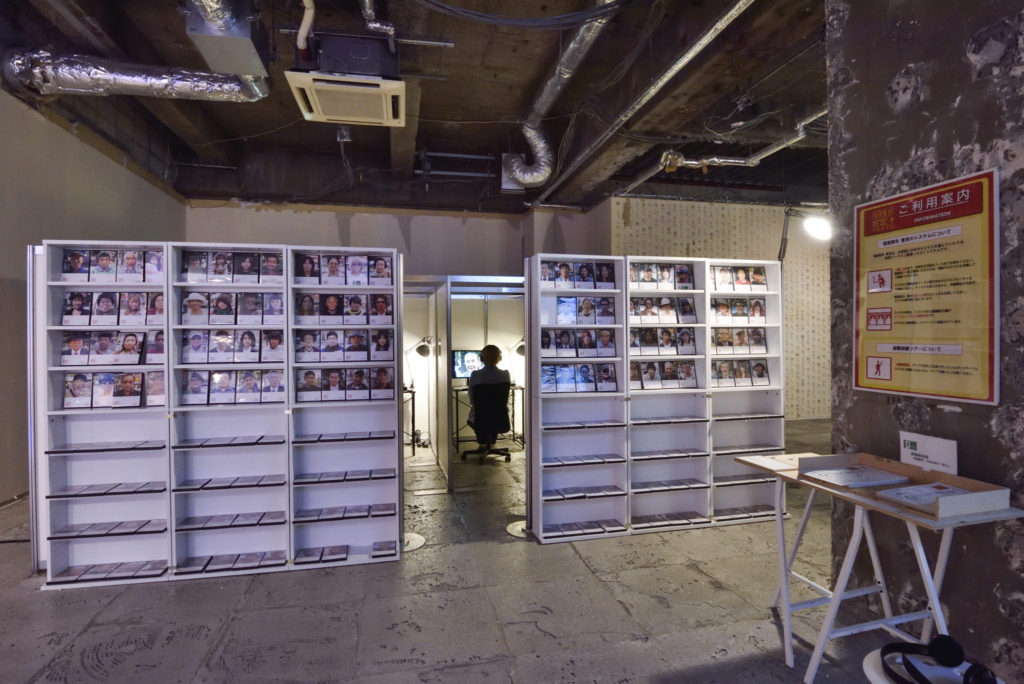

Akira Takayama “Compartment City Tokyo 2019” © TOKYO 2021 Executive Committee Photo: Mitsuhisa Mitsuya

A work that cut particularly deep down into the city of Tokyo in this area was Akira Takayama’s “Compartment City Tokyo 2019.” The visitor chooses DVDs – limited to three at a time – to watch them one by one in a somewhat suspicious private viewing room. The DVDs show interviews with people of all ages and sexes, and with different backgrounds, shot at Ikebukuro’s Nishiguchi Park. Asked in quick succession, the questions eventually touch upon the interviewees’ awareness regarding such issues as immigrants, refugees and homeless people. The individual answers – apparently extracted in a random fashion – highlight the awareness of “us,” the countless individuals living in Tokyo today. Only after watching the footage for quite a while, I realized that they were made ten years ago. The redevelopment of the Nishiguchi Park was completed just recently, and the place now looks very different. After watching the randomly chosen interviews with a number of people comes the next instruction to be followed. The route given by Takayama is marked by guidance lights for evacuation purposes, and following that route that is normally only used in emergency cases triggers flashbacks of the experience of the Great East Japan Earthquake. Awaiting the visitor at the end of the route is another set of interview footage, this time obviously shot more recently. Quite surprisingly, some of the people from the first interviews appear once again. The interviews urged me to imagine myself ten years ago and today, and ponder how I would have answered the questions.

Kazuhiko Hiwa “hiwadrome: type THE END spec5 CODE: invisible circus” in cooperation with KOTOBUKI CORPORATION, KOTOBUKI SEATING CO., LTD. © TOKYO 2021 Executive Committee Photo: Mitsuhisa Mitsuya

Kanji Yumisashi “Black Bon Dance” 2019 © TOKYO 2021 Executive Committee Photo: Mitsuhisa Mitsuya

Kanji Yumisashi “White Horse” 2019 © TOKYO 2021 Executive Committee Photo: Mitsuhisa Mitsuya

In the second area, “SiteB: Shukusai no kuni (land of festivities),” visitors were greeted by a down-sized version of the face of Taro Okamoto’s “The Tower of the Sun,” here sitting on the boisterous pile of wheelchairs and fluorescent lamps that is Kazuhiko Hiwa’s installation “hiwadrome: type THE END spec5 CODE: invisible circus.” While referencing the Osaka Expo 1970, Hiwa used again wheelchairs – like in the work for which he received the TARO Award in 2019 – to create a festive scenery in the form of a tower that emits lights. This object is paired with footage of the physically handicapped artist himself into a composite installation. Kanji Yumisashi’s “Black Bon Dance,” juxtaposing black lanterns and dancing human figures wearing Hyottoko (man with a clownish face) or Okame (plain faced woman), deals with Japanese festivals themed around life and death. “White Horse,” another work by Yumisaki, deals with the war experiences of the aforementioned Taro Okamoto, depicting the corpse of a horse covered with maggots.

Houxo Que “un/breakable engine” 2019 © TOKYO 2021 Executive Committee Photo: Mitsuhisa Mitsuya

Other works exhibited at the same venue included Akira Fujimoto’s “2026,” made of waste materials that were removed from the floors and walls when setting up the exhibition space, and Houxo Que’s “un/breakable engine,” for which the artist created a pool of water in a basement room he had made waterproof. While borrowing from the sponsor’s background as a construction company, these works were somehow also reminiscent of the scrap-and-build style and construction techniques that have come to define the Tokyo cityscape. Kurose employed an array of artists to illustrate a large number of topics, while distributing explanatory flyers to help visitors enjoy his storytelling. It was a sincere exhibition that inspired visitors to think, and also in this respect it perfectly reflected Kurose’s skills in contemporary communication.

Installation view © TOKYO 2021 Executive Committee Photo: Mitsuhisa Mitsuya

During the period of the exhibition, there were several problems related to art festivals and exhibitions hosted by public institutions, including the Aichi Triennale. A discussion of these issue doesn’t belong here, so I leave that to others, but I do feel the significance of the fact that a private enterprise like Toda Kensetsu hosts an exhibition of critical works of art and architecture in such kind of situation. After the closing of the 2020 Olympic & Paralympic Games in Tokyo, the next spectacle awaits us with the Osaka Expo in 2025. While it is difficult to deny that notion of successive “city doping,” Kurose’s story did help detect also the germination of new possibilities. On the other hand, however, I cannot help but see the rejection of Zaha Hadid’s proposal for the National Stadium as a missed opportunity for new engineering. There is an expression in Japanese that roughly translates into “after the fact,” and in order to avoid that situation of regretting after the fact in 2021, we must keep thinking. This is what the exhibition made me keenly realize.

INFORMATION

TOKYO 2021

Duration: 2019. 8. 3 - 10. 20

Architecture exhibition: 8. 3 - 8. 24 / Art exhibition: 9. 4 - 10. 20

Venue: TODA BUILDING 1F

Organized by TODA CORPORATION

Directed by Akira Fujimoto

Advised by Yuko Nagayama