Curator and coordinator. Lives and Works in Tokyo. Having worked as an assistant curator of Mori Art Museum, Tokyo (2001-9), she then moved to New Delhi India between 2009-18. While in India, she coordinated and researched for numerous projects. Worked as a project coordinator of Japan Foundation’s “Omnilogue: Journey to the West” at Lalit Kala Akademi, New Delhi in 2012, a research curator of Indian art for the Fukuoka Asian Art Triennale 2014, and coordinated to create a new video and painting installation of “The Returns of K.T.O.” by Japanese artist Tsuyoshi Ozawa for Yokohama Triennale 2017. Recent coordination is “Eiko Ishioka – Blood, Sweat , and Tears – A Life of Design ” at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Tokyo.

Tsuyoshi Ozawa, The Return of S.T., 2020 Installation view, Photo: Tomoyuki Kusunose Courtesy of Hirosaki Museum of Contemporary Art

Tsuyoshi Ozawa ALL RETURN: “Come back in a hundred years’ time. After a hundred years you’ll understand.”

The new piece “The Return of S.T.”

Tsuyoshi Ozawa’s exhibition “Come back in a hundred years’ time. After a hundred years you’ll understand.” is currently showing in Hirosaki City, Aomori. The venue is a former cider brewery that was established in the Meiji/Taisho era, and that now houses the Hirosaki Museum of Contemporary Art. This exhibition is the second at the museum since its opening in July 2020. On display are a total of five works – four from the “The Return of…” series that Ozawa has been working on since 2013, and a new one. This is at once the first occasion at which all parts in the series come together, in a space that has been renovated by architect Tsuyoshi Tane based on the concept of “Inheritance of the memories.”

Tsuyoshi Ozawa, The Return of J.L., 2016 Installation view, Photo: Tomoyuki Kusunose Courtesy of Hirosaki Museum of Contemporary Art

OZAWA Tsuyoshi, The Return of J.L. (detail), 2016 Courtesy of the Artist

Each of the featured works was modeled after one modern historical figure that has been operating on a global scale, portraying a fictitious person’s life and death, and telling a fictional story that may have been reality if that person was alive today. All this is illustrated by means of hand-drawn picture signboards, music and imagery that portray modern and contemporary-era Japan in critical yet humorous ways. The figures that have been “brought back to life” through Ozawa’s works so far are Hideyo Noguchi, Tsuguharu Foujita, John Lennon, and Kakuzo (Tenshin) Okakura. While all of them were great and famous men with exceptional talents, here we see them struggle, as these works focus on their basic human aspects. Characteristic of these works is also the fact that they were produced at places in countries that are in one way or other related to the respective figure. The previous volumes were set in Accra (Ghana), Bali (Indonesia), Manila (Philippines) and Kolkata (India). As an additional highlight in this exhibition, they are presented alongside various related materials that shed light on the creative processes of each of these works.

Roundtable Meeting Room: Archive of the Returnees and the 100 Years, Photo: Tomoyuki Kusunose Courtesy of Hirosaki Museum of Contemporary Art

The protagonist in the new piece, titled “The Return of S.T.,” is Aomori-born Shuji Terayama (S.T.), who makes his “return” to Hirosaki here. Terayama is known for his artistic endeavors in the realms of poetry, experimental theater and cinema, but as a creator of popular songs among others, he was equally at home also in mass culture. In addition to these activities, he was also known as a critic in competitive sports like horse racing and boxing. As a boy that had lost his father in the war, and was abandoned by his mother, Terayama grew up under rather complicated circumstances in the Tohoku region, and the childhood experiences of those early postwar years left their mark on his entire life. Ozawa picked up the story of Terayama, who eventually sought refuge in the world of fiction as a place where he would be accepted, and created a fictional narrative of what may have been, with an eye to modern art and history. It is somewhere around the idea of “somewhere else but not here,” where the two of them occupy the same kind of mental place. The second half of this exhibition’s title, “After a hundred years…,” was taken from a line in one of Terayama’s late movies. This somewhat prophetic phrase resonates beyond space and time with the very idea behind the “The Return of…” series: face the past, consider the now, and feed the future, at places built from construction materials that were used back in the day.

Tsuyoshi Ozawa, The Return of S.T., 2020 Installation view, Photo: Tomoyuki Kusunose Courtesy of Hirosaki Museum of Contemporary Art

Tsuyoshi Ozawa, The Return of S.T. (Original painting), 2020, Photo: Tomoyuki Kusunose Courtesy of Hirosaki Museum of Contemporary Art

In a space with a high vaulted ceiling, locally made traditional neputa (large, fan-shaped floats with epic and fantastic images, used at festivals) surround the new work “S.T.” like a stage set that evokes images of Aomori landscapes. Terayama had initially launched his theatrical troupe Tenjo Sajiki under the banner of a “revival of the show tent,” and likewise, Ozawa has been exploring the relationship between traditional crafts and modern art with a focus on show tents as places for presenting the latest in art, in times when museums were yet to be established in Japan. This work can be seen as another effort on that same vein.

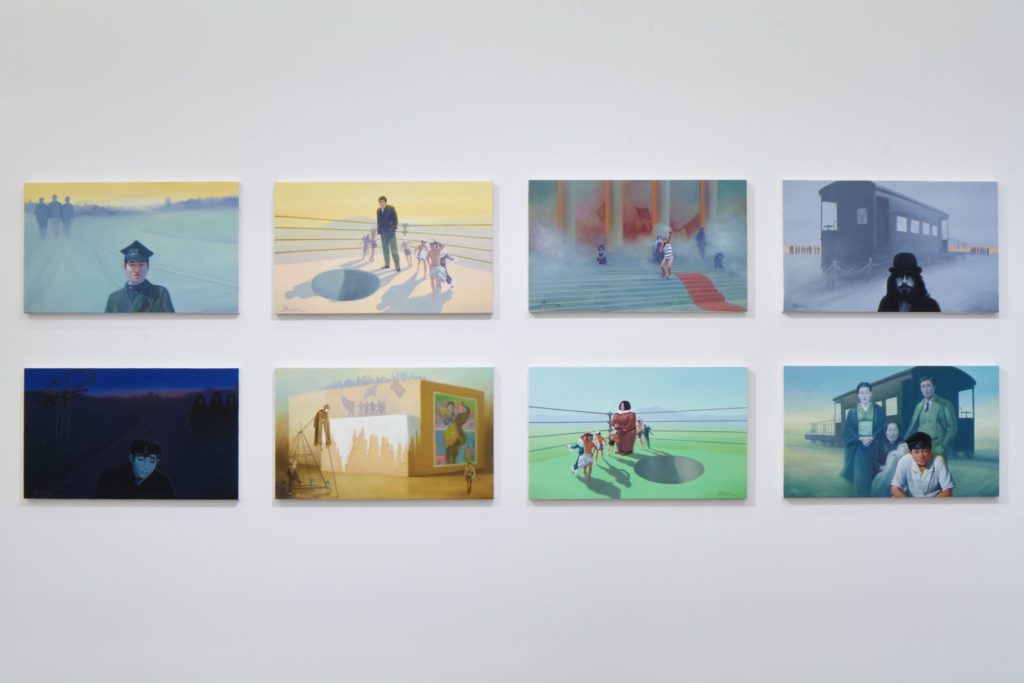

Created in Hirosaki and Iran, the work was mainly inspired by the fact that Terayama had been invited twice to Iranian theater festivals, where the performances of Tenjo Sajiki reportedly had a considerable impact on the local theater scene. It is studded with Terayama’s quotes and images, including eight sketches and lyrics starting with one of Terayama’s favorite lines, “Yureru kisha no naka de umareta (“Born in a swaying train”).” Ozawa actually traveled to Iran in the footsteps of Shuji Terayama, and constructed the fictional story of S.T. by adding any matter of interest that he encountered along the way. Like in the other works in this series, Ozawa’s original plot was visualized in paintings by a signboard painter, lyrics translated into English and the local language – Persian in this case – and music contributed by members of the local Otagh Band, all of which was ultimately blended together in a music video that also features other footage shot in Hirosaki and Iran. Each exhibition in this series is accompanied by a printed publication that serves as a manual for gaining insight into the respective project and the underlying story, featuring a mixture of essays by the curators and local academics, Ozawa’s own production diary, and information on collaborators.

Tsuyoshi Ozawa, The Return of S.T., 2020 (partial) Collection of Hirosaki Museum of Contemporary Art Courtesy of the Artist

If there is one notable difference between this and previous works, it has to be its creators’ formidable evasion of limitations to the freedom of expression. When asking Ozawa about this, he explained that these things had been on his mind even before working in Iran, as he had experienced censorship for exhibitions in China, and witnessed how Chinese artists evaded that for the The Second Ghangzhou Triennale in 2005.[1] For this work, he teamed up with a local band that has been operating in the public while struggling to overcome restrictions of public artistic expression in Iran, and tell in their songs about “There are expressions that slip through the grate of human history.” For the oil paintings featured in his work, Ozawa accepted certain modifications, as the painter would have risked imprisonment if he adopted the sketch of Debuko Oyama, showing bare skin as it was. Just like Ozawa’s own early works of “sodan art”[2], in which he subsequently altered paintings that other people had started, within the cultural exchange between two nations, the “The Return of…” series gradually turned into a work of art beyond the powers of individual creators.

Tsuyoshi Ozawa, The Return of S.T., 2020 Installation view, Photo: Tomoyuki Kusunose Courtesy of Hirosaki Museum of Contemporary Art

As it seems, the creative process remained thrilling until the very end. Following anti-government demonstrations in Iran in late 2019, and the assassination of General Soleimani that further worsened the political situation between Iran and the United States, in 2020 it was Covid-19 that made working in Iran impossible. Ozawa had to make last-minute arrangements and switch from on-location shooting to indoor and remote operations, and wasn’t even able to go and pick up the paintings that, considering the weak logistic infrastructure in Iran, were made small enough to fit into hand luggage. Instead, coordinator Megumi Shimizu sent a representative to the artist’s remote studio in order to collect the paintings, which were then given to a Japanese resident in Tehran, who carried them in her hand luggage during her emergency return to Japan. For the displays at Hirosaki, the original paintings were enlarged and color printed onto signboards.

While it is easy to imagine that there were more misunderstandings, misinterpretations and accidents involved than in any of the previous projects, there are also new creative aspects that were inspired through this form of collaboration. At the final stage of the creative process, it is a usual practice for Ozawa to add a Japanese chorus and images to the locally recorded music and video footage. Considering that the Iranian people enjoy poetry on a daily basis, for this work the Iranian side suggested combining Otagh Band’s play and song with Japanese lyrics recited by Ozawa himself, and on top of that, Tsugaru-jamisen (Japanese stringed instrument) player Kaoru Osanai’s shamisen performance and lyrics in Tsuruga dialect. In a space that is filled with a mixture of forceful Persian musical instruments and the sharp sound of the Tsugaru-jamisen, Ozawa gives the lyrics a body and a voice, and against the backdrop of growing intolerance around the world, that voice sounds like an encouragement to “Speak eloquently in difficult times.”

Notes

[1] See also http://archive.realtokyo.co.jp/docs/en/column/40nen/bn/40nen_sp_en/

[2] “Art born out of communication with the audience.” Devised and applied by Ozawa since the 1990s, this creative method developed in various ways, inspiring among others the “University of Sodan Art” and the “Sodan Art Café.”

INFORMATION

Tsuyoshi Ozawa All Return: “Come back in a hundred years’ time. After a hundred years you’ll understand.”

Organized by Hirosaki Museum of Contemporary Art

Special Sponsor: Starts Corporation Inc.

Sponsor: NTT FACILITIES, INC.

Supported by The To-o Nippo Press, THE MUTSU SHIMPO Press, Aomori Broadcasting Corporation, Aomori Television Broadcasting Co., Ltd., Asahi Broadcasting Aomori Co., Ltd., Aomori Fm

Broadcasting, FM APPLE WAVE, Hirosaki City Board of Education