Founder of Studio KIKIRIKI, which organizes exhibitions and events and conducts artistic research for government entities and corporations. Draws on the public nature of European (particularly German) contemporary art and on the design of memory in the contemporary German community, rooted in the experience of World War II and the subsequent division of the country into East and West. Recent projects include “10 Major Cases in the 140-Year History of the Metropolitan Police Department, As Selected by its Employees” (Metropolitan Police Department, 2014), and “ASATTE NO EKI: Stations and lifestyles of the future” (JR East, 2019). Fukazawa is a graduate of the Karlsruhe University of Arts and Design (Media art).

The novel coronavirus pandemic that suddenly exploded upon us in late 2019 has affected people all around the world simultaneously, demonstrating the overwhelming power of nature. Meeting face to face has become taboo, and our daily lives remain filled with fear of infection. The future of society, and indeed the human race, is uncertain, and we feel this more acutely than perhaps ever before.

The two-day Art & Media Dialogue, organized by Arts Council Tokyo, took place in March 2021 during a state of emergency. The first day saw discussion on the pro-democracy demonstrations in Hong Kong and on the Thai protest movement that opposes military rule[1] , while climate change and other global environmental issues were in focus on the second day. This drove home how Covid-19 is far from the only global problem we are faced with right now.

“Know what is going on around the world, and think about the future of society from the perspective of art that confronts current issues. Do we see what is happening elsewhere in Asia, right on our doorstep? Are we aware of the Earth’s ecology? Understanding these things takes imagination.” The organizers’ introductory message called upon participants to seek knowledge on their own.

The event was positioned as a follow-up to the Art & Media Forum, held in December 2019. The switch from “forum” to “dialogue” perhaps sought to encourage an even freer exchange of opinions and to keep the conversation going.

Art & Media Dialogue was planned by curator Junya Yamamine, who was also the driving force behind the Forum, together with editor and curator Arina Tsukada. The event was held online, as has become the norm in the pandemic age, and on both days featured graphic recording by Junko Shimizu, whose efforts helped visualize the discussion, aiding participants during impassioned debates that went on for three hours on both days.

■Part 1: Asian-style cultural resistance

Day 1 started with presentations by Eric Siu, an artist and expert on the pro-democracy movement in Hong Kong, and researcher Arthit Suriyawongkul, whose subject is the democratization movement in Thailand. The presenters then participated in a five-way discussion with Yamamine, Tsukada, and media and cultural theorist Tomoko Shimizu.

The democracy movement in Hong Kong

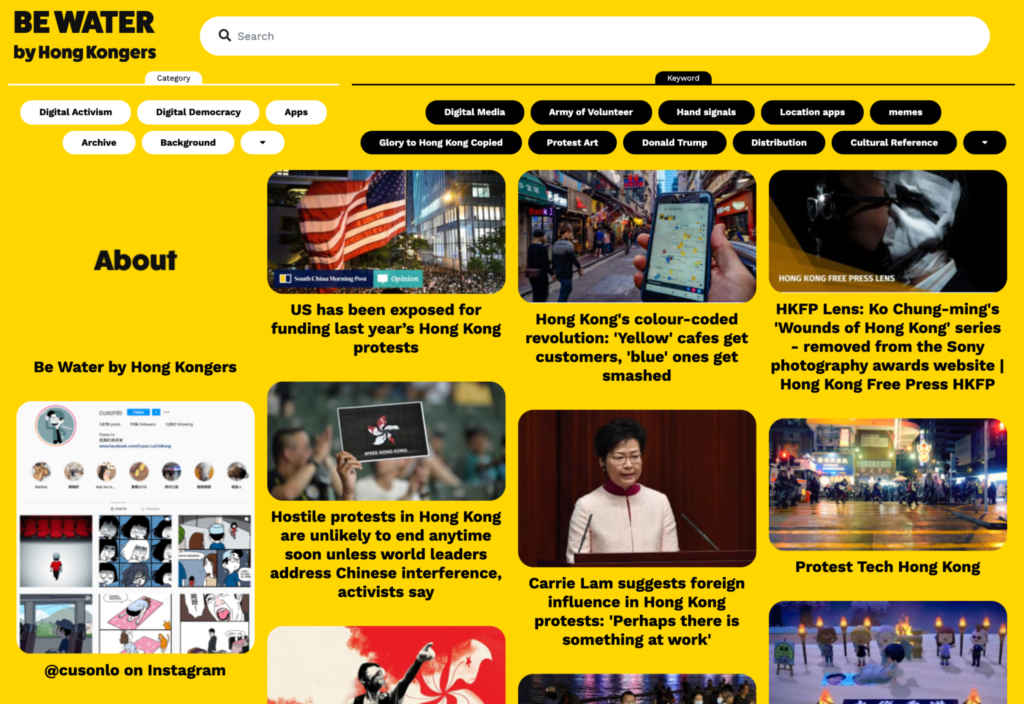

Source: BE WATER by Hong Kongners

The Hong Kong-born, Tokyo-based Siu gave a report on the internet activism of Hong Kong’s democracy advocates. He described how the protest movement of 2020, drawing lessons from the Umbrella Movement of 2014, has adopted a leaderless structure. The actions of individuals form an organic whole, in which ideas emerge and are shared one after the other. Digital technology is the infrastructure that allows for such activism. Any tool can be of use, be it livestreaming, bulletin boards and apps, e-commerce platforms, websites, or music. Besides using existing services, the activists have also developed platforms of their own.

An app designed to assist with making purchases at businesses supportive of the pro-democracy movement Images collected by Eric Siu

Through these means, Participation in the movement has been made uncomplicated, for example by achieving decision-making through citizen participation and a transparent process on online platforms or organizing demonstrations by sharing location data with AirDrop. The activists have also formed a strong international support network by making their concerns heard, be it by publishing crowdfunded full-page ads in newspapers around the world, sharing protest art in the form of images, video, and music, or livestreaming actual protests.

The protest movement in Thailand

photo by iLaw

The protests in Thailand, which started in mid-2020, were influenced by the movement in Hong Kong and have adopted many of its methods. Suriyawongkul’s presentation on the Thai movement touched on its historical origins, and argued that it stands out particularly for its ingenious use of nonverbal symbols such as images, icons, and (rap) music. The protestors’ “three demands” are expressed with a three-finger salute originally from the movie Hunger Games. The theme song from the Japanese anime Hamtaro has been sung with modified lyrics during demonstrations, and imagery from Attack On Titan has been used to make the point that the Thai military cannot be trusted. The movement opposing military rule has also extended criticism to the royal family, appropriated many historical and cultural symbols of Thailand, and used the music of the royal family and royal pronouncements as the stuff of parody and jokes. Just like in Hong Kong, these have been recorded and shared on platforms such as YouTube, becoming internet memes both within and outside of Thailand.

Suriyawongkul’s presentation touched on how humor is an extremely important component of the Thai protest movement. It is primarily a means of protecting yourself, as Thailand’s lèse-majesté laws prohibit direct criticism of the royal family. Many people are also highly devoted to the royals, so it would be unwise for the protestors to upset the public needlessly. Additionally, humor helps make fighting for democracy fun, and is a means of getting people without knowledge of politics to participate.

Dinosaur dance on stage by “Bad students” create incredible colors for the mob I Springnews I 21 Nov ’20

Dialogue

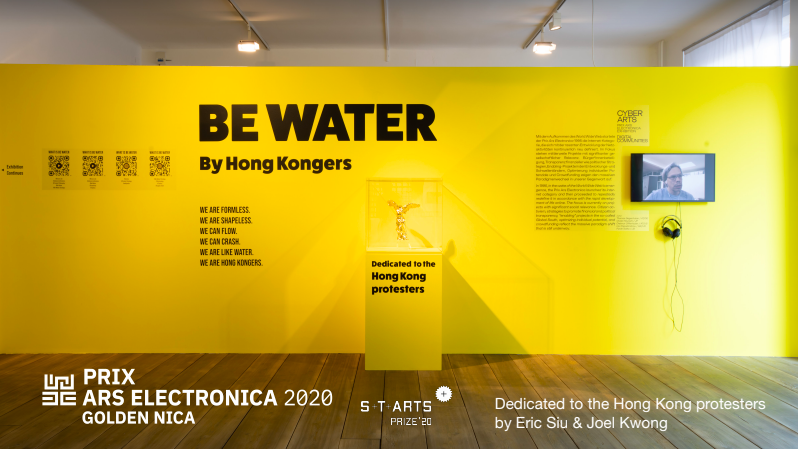

Both the Hong Kong and Thailand presentations were full of practical examples. According to Shimizu, both citizen movements “employ remarkable levels of translation ability and creativity to take ownership of democracy and utilize it to their benefit” – something that the discussion proved vividly. Siu, together with Joel Kwong, built the “BE WATER” website to encourage people around the world to keep track of developments in the Hong Kong pro-democracy movement. As a result, the movement won the Golden Nica grand prize in the Digital Communities category at Ars Electronica 2020, and it is easy to agree with the awards jury’s praise for the movement as a digital community formed through the creative use of technology.

The nature of pro-democracy movements may well come to be classified into pre- and post-Hong Kong styles. Shimizu pointed out two characteristics that distinguish the Hong Kong protesters from past protest movements. One is the extensive use of symbols such as characters and gestures, as opposed to the slogans of the past. Another is how its strategy emphasizes fun and safety. The avoidance of full-on clashes as a way of keeping the movement going is another new ingredient.

How the citizens’ movement in Hong Kong moves effortlessly between online and real-world spaces, and how these spaces overlap, appears to produce an illusion that the ideal network society pursued in the 1980s is finally coming to partial fruition. This brings to mind the concept of a “disaster utopia,” but the movement’s use of technology to its benefit is hardly something that will be limited to times of disaster.

The Ars Electronica 2020 Golden Nica exhibition Courtesy of OK Center, Linz

Tsukada’s suggestion that movements connected by civil tech and social media are spreading far beyond Asia was taken up by Shimizu, who noted that the very meaning of people gathering is changing, and that the coronavirus crisis appears to be accelerating the development of new methods of getting together. As suggested by the philosophy of “BE WATER” – the Bruce Lee quote adopted by the pro-democracy movement in Hong Kong – the act of gathering is becoming a more versatile and ever-changing concept.

That trend was evidenced during the event, when Bess Lee of Taiwan’s g0v, who had been observing the discussion, suddenly joined the conversation. She asked whether there was anything g0v could do to help Hong Kong and Thailand, and this question sparked a practical exchange between the three movements.

Dialogue participants (from top left): Junya Yamamine, Arina Tsukada, Tomoko Shimizu, Graphic recording on screen, Eric Siu, Bess Lee, Artist Suriyawongkul © Arts Council Tokyo, 2021

The word from Taiwan was that g0v also exists in Hong Kong, but that the situation is dangerous and the Taiwanese side has not been able to provide support. The Hong Kong side brought up the need for local support aimed at people who move from Hong Kong to Taiwan, to help them get adjusted to their new environment. Thailand’s question of how to organize the decision-making process in a leaderless movement was answered by the Taiwanese, who argued that leaders are not needed and that the key is to ensure transparency by having the people responsible for each project offer thorough progress reports online. Information was also exchanged on matters such as open source tools and the reliability of social media.

The participants all appeared relaxed, speaking briefly and to the point without adding anything superfluous. The five-minute online discussion that followed Lee jumping in conveyed the tense atmosphere of pro-democracy movements and made for an undeniably real experience.

■Part 2: Human society reconsidered from a global ecological point of view

Day 2 was themed on the issue of climate change. Presentations were given by curator Martin Guinard-Terrin, whose work includes planning an exhibition themed on consensus-building related to climate change, and Peter Steffensen, editor of the art magazine Plethora Magazine. Their talks were followed by a seven-member discussion with panelists Junya Yamamine, Arina Tsukada, architect Taichi Sunayama, speculative designer Kazuya Kawasaki, and artist Ai Hasegawa.

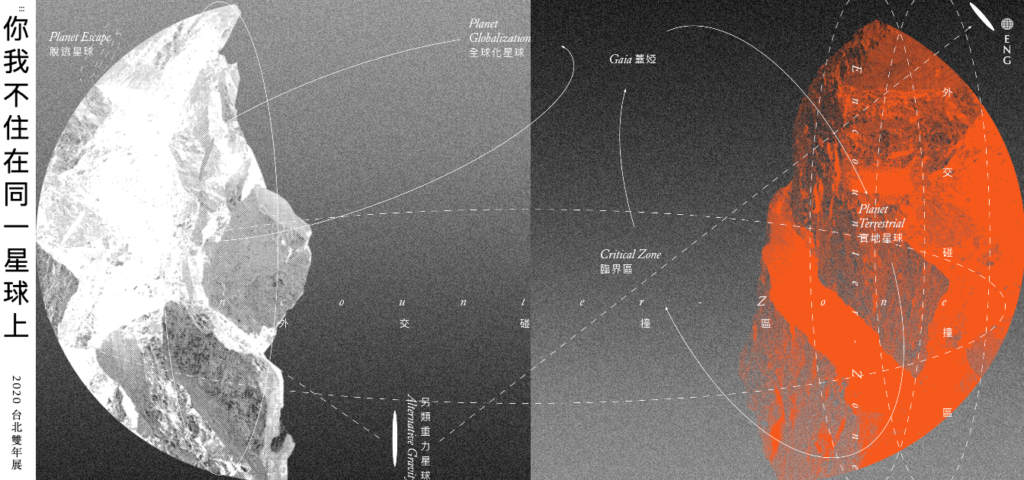

The 2020 Taipei Biennial

2020 Taipei Biennial Courtesy of Taipei Fine Arts Museum

Guinard-Terrin’s presentation focused on the 2020 Taipei Biennial, which he curated together with the philosopher Bruno Latour. The concept was “You and I Don’t Live on the Same Planet.” The greatest problem with global, planet-wide issues including climate change, the rise of populism in democratic societies, and the emergence of new authoritarian regimes is a lack of shared premises for debate. The Biennial provided an allegorical take on our current predicament to reveal the unbridgeable gap, formed by conflict and indifference, that prevents agreement on the premises for communication.

The various planets on display reflected the ideas and beliefs held by people in contemporary societies. Some want to keep living in a society with sustained economic growth, some want to escape the problem altogether, some want to be protected by walls, and others hope to enjoy prosperity while accepting certain limits in life. The exhibition highlighted the worldviews of each planet by placing them in a giant installation that covered the entire exhibition space, thereby expressing how different our value systems are. In addition to the viewing experience, workshops were offered to allow members of the audience to engage in dialogue and deepen understanding of each other’s differences. An extension of the exhibition itself, this “travel between planets” added a theatrical element.

Plethora Magazine

Plethora Magazine Courtesy of Plethora Magaizne

Steffensen spoke about Plethora Magazine, of which he is editor-in-chief. A journal that combines artistic and scientific themes, it fuses natural, scientific, cybernetic, futuristic, and other topics, traversing the past and the future to provide a contemporary perspective on themes both global and universal. Sized at an impressive 70 x 50 cm and printed in ultra-high definition, it offers the reader an immersive experience.

The aim of Plethora is to “search for a way to live in harmony with nature by accepting the things around us as they are and projecting them through the prism of language, images, and art.” This mission is driven by Steffensen’s understanding that human wisdom is in urgent need of an update.

The latest issue, No. 10, is themed on pandemics and entitled “Theia Mania – The Wrath of the Gods.” Some pages highlight the history of viruses through centuries-old microscope images, while others feature the mythology of the Tower of Babel. The timeliness of that allegory, in which people who used to share a language become scattered and truth becomes relative, is conveyed with a selection of tower-themed images and explanatory text.

Dialogue

Guinard-Terrin, Steffensen, and the other dialogue participants are all creatives who through their activities provide society with experiences. Their discussion touched on everything from our planet, the world, humanity, and culture to the incentives and process of creation and to the feelings and thoughts brought about by it. Opinions were exchanged vigorously on matters both macro and micro, global and personal, and natural and human, as well as on how to communicate with others. Several times during the discussion, participants cycled back to reference the concept of ecology. On the relationship between nature and humanity, Guinard-Terrin repeatedly emphasized how ecology is less a single topic than a fundamental worldview, or essential infrastructure for living.

That may actually be self-evident in the Japanese view of nature. Hasegawa noted how Japanese religion is an amalgamation of many different ways of thinking, and that she was surprised to find that the Japanese themselves do not realize this. She finds the idea that all things are imbued with life, and how this permeates Japanese thinking, something to be proud of.

That the West and Japan have different understandings of nature and science was clearly revealed in the two sides’ approaches to developing a coronavirus vaccine. Some 7 trillion yen – more than 2 trillion of that in the United States alone – may have been invested into vaccine development. The “battle” against the virus was positioned as an Apollo Program for our time and nicknamed Operation Warp Speed, producing a vaccine in only six months. That idea probably couldn’t have originated in Japan.

In comparison to the populations of other countries, the Japanese appear less than eager to be vaccinated. This is perhaps also due to the aforementioned view of nature. On a related note, Kawasaki spoke about growing bacteria for a work of bio-art, describing the experience as one of nurture rather than production. Hasegawa, on the other hand, is exploring the possibility of using technology to simulate herself giving birth to a dolphin and seducing a shark. Both artists are aiming to build a relationship with nature that is not based on fighting, dominating, or controlling it.

As for the solution of environmental problems, it all comes down to shared premises and the process of consensus-building. Guinard-Terrin asked the Japanese participants whether there have been any successful examples of this difficult process in Japan, and whether Japan has demonstrated initiative in international consensus-building. Tsukada, Hasegawa, and Kawasaki replied by discussing anime and manga, both means of storytelling originally developed in Japan. Many manga artists are women, and stories told from a woman’s perspective have long been popular. In that sense, the ideology of female manga artists has had a significant influence on the personal development of today’s women. Kawasaki also mentioned Japan’s traditional craftsmanship as another example.

At the same time, the discussion touched on the lack of a debate culture in Japan. Debating is a skill that furthers mutual understanding. According to Sunayama, rather than being averse to debate, people are unable to discuss the issues because they lack the incentive to do so. For him, the problem is that macro-level issues such as climate change are difficult to grasp as something that affects you personally. Guinard-Terrin, discussing strategies for debating people you don’t agree with, suggested a “diplomatic” approach, i.e. attempting to arrive at a common interest. Yamamine, Guinard-Terrin, and Sunayama agreed on the importance of establishing linkages between separate fields as hubs of communication in order to encourage dialogue.

In the past, people’s movements have been able to make environmental issues feel personal. Such movements sprung up around the world in the 1960s, and the issues they raised – protection of the environment, nuclear nonproliferation and renewable energy, peace (anti-war), feminism, civil rights, and so on – continue to form the foundation for much of today’s debate. That is because those movements spoke up against the excesses of capitalism and were anti-capitalist and anti-consumerist in nature. They resulted in the establishment of, to name only a few examples, Greenpeace and the Green Party. Groups that can enact change both within and outside the structures of power are permeated by a movement mentality. Joseph Beuys took part in the formation of the German Green Party.

Sunayama noted that people have been pointing out the limits of globalism built on the foundation of modernism for 50 years now. Back then, the Club of Rome, composed of the world’s elites, released a report that opened with warnings about population growth and environmental catastrophe. That said, seeing that the actual protest movements of the past formed the foundation for contemporary debate, it seems rather strange that their experience is rarely told in the form communal memory. People who were part of those movements are still active today, but the issue itself is hardly ever raised – especially so in Japan. Had the flower-child generation been able to get involved in government in Japan, as it did in Germany, perhaps we would have less of a generational gap in perceptions and more gender and generational balance in politics. This suggests the great value of initiatives such as Siu’s archiving of the pro-democracy movement in Hong Kong and the efforts of the Milk Tea Alliance, an Asian democratic solidarity movement.

Meanwhile, the spirit of the people’s movements appears to be alive and well in the world of contemporary art. Dialogue, the purpose of this event, was also the basis for Beuys’s activities. In his words, everyone is an artist and society is a creative sculpture; having realized that all forms of expression are political, he took his art from the museum out to society, taking part in its full diversity of dialogue – from politics and environmentalism to social work. The importance of art to society lies not only in its power of expression, but in its ability to open up new avenues of thought as artists pursue what they deem necessary.

Dialogue participants (from top left): Peter Steffensen, Martin Guinard-Terrin, Arina Tsukada, Kazuya Kawasaki, Taichi Sunayama, Junya Yamamine, Ai Hasegawa, Graphic recording on screen © Arts Council Tokyo, 2021

■Continuing the dialogue

The two dialogue-filled days were highly satisfying and provided plenty of food for thought. The discussion felt very approachable, possibly because online meetings have become such an obvious part of life during the pandemic. A chat-based Q&A helped add to the impression of closeness between the audience and the participants.

The presentations on the current state of Hong Kong and Thailand’s pro-democracy movements conveyed the true situation in the field more vividly than any news report could, while the dialogue that covered climate change as well as a wide range of other themes helped with the realization that thinking by expressing yourself, rather than being a passive recipient, is key to making the issues feel personal. The debates also drew attention to cultural differences between Asia and Europe, especially in terms of Asia’s positivity and Europe’s depth of introspection.

Half a century now separates us from the movements of ’68, and people no longer say “Save the planet.” Information technology has permeated our lives. And Asia, an important frame of reference for the movements of the past, is now relaying its messages to the world. The practical resistance of Asia’s digital communities feels like one way of confronting human needs different from those of the environmental business and the SDGs, and provides hints that further and cultivate the dramatization of philosophical, scientific, and other types of knowledge. What stuck with me was the somewhat perplexed look on Lee’s face when she pondered how to explain why leaders and strategy-building aren’t needed.

After the presentations on Day 1, Tsukada said that “We tend to think in terms of ‘OK, so what should we do?’.” She was absolutely right: when confronted with a big theme, we often feel powerless, frustrated, weary, or far more excited than before. More than anything, I think this event called upon us to continue talking to each other in order to think for ourselves and take action. I hope to do so wherever possible – all while looking forward to future developments .

Translated by Ilmari Saarinen

INFORMATION

Art & Media Dialogue

Theme 1: Asian-style cultural resistance

Theme 2: Human society reconsidered from a global ecological point of view

Organized: Arts Council Tokyo (Tokyo Metropolitan Foundation for History and Culture)

Venues: Online (Zoom Webinar)

Planning: Junya Yamamine (Tokyo Art Acceleration), Arina Tsukada (Whole Universe)

Planning cooperation: Keiko Sei

Period: Part 1: Saturday, March 6 2021, 18:00-21:00, Part 2: Sunday, March 7 2021, 18:00-21:00

Theme 1: Asian-style cultural resistance

Guest Speakers: Eric Siu (Artist, “Be Water”, Hong Kong/Tokyo), Artist Suriyawongkul (AI ethicist, data governance researcher, Thai Netizen Network, Thailand)

Guests: Tomoko Shimizu (Media/cultural theorist /Associate professor at Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences, University of Tsukuba, Japan)

Moderators: Junya Yamamine (Curator, Co-founder of Tokyo Art Acceleration, Director of ANB Tokyo, Japan), Arina Tsukada (Editor, Curator, Founder of The Whole Universe Association, Japan)

Graphic Recorder: Junko Shimizu (Design Researcher, Graphic Recorder, Japan)

Theme 2: Human society reconsidered from a global ecological point of view

Guest Speakers: Martin Guinard-Terrin (Curator, Luma Foundation, France), Peter Steffensen (Editor in chief, PLETHORA MAGAZINE, Denmark)

Guest: Ai Hasegawa (Artist, Designer, Japan), Kazuya Kawasaki (Speculative Fashion Designer, Design Researcher, Director of Synflux, Japan), Taichi Sunayama (Architect, Artist, President of sunayamastudio, Japan)

Moderators: Junya Yamamine (Curator, Co-founder of Tokyo Art Acceleration, Director of ANB Tokyo, Japan), Arina Tsukada (Editor, Curator, Founder of The Whole Universe Association, Japan)

Graphic Recorder: Junko Shimizu (Design Researcher, Graphic Recorder, Japan)