Born in Aichi. Associate professor at the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences, Tsukuba University, specializing in media and cultural theory. Publications include Culture and Violence: The Unravelling Union Jack(Getsuyosha), Community-Engaged Art Project(joint authorship, Horinouchi Publishing), Art and Labour(joint authorship, Suiseisha), and Towards the 21st Century Philosophy(joint authorship, Minerva Shobo). Translations include Judith Butler, Notes Toward a Performative Theory of Assembly(co-translation, Seidosha) and Antonio Negri & Michael Hardt, Declaration(co-translation, NHK Publishing).

photo by Shimpei Shimokawa

Cultural Resistance in the Post-Open Data Age

“Cultural Resistance in the Post-Open Data Age” was the title of a Forum for Social Practice in Art/Media organized in December 2019 by Arts Council Tokyo. The forum was planned by curator Junya Yamamine, who has been active in raising social discussion on the contemporary media environment and its issues through exhibitions such as “Hello World For the Post-Human Age” and “Resistance of Fog: Fujiko Nakaya.” Yamamine’s main talking point at the forum was the strong sense of crisis he feels toward a closed society that robs people of their words and causes them to stop thinking, and how that brings about a crisis of democracy.

Junya Yamamine photo by Shimpei Shimokawa

The advancement of media and technology is both having a significant impact on the environments we live in and causing a major tectonic shift in how we perceive the world. Urban environments are whirlpools of vast amounts of personal information and data. As social media becomes ubiquitous and massive amounts of largely user-produced data are exchanged, we retreat into comfortable “information cocoons” (Cass R. Sunstein). We are living in a “post-truth” era in which appeals to emotions and personal beliefs are more influential than objective truths. How, under these circumstances, should art interact with media and technology, and can it fulfill its potential as a transformative force in society?

The December forum saw lively debate on these very questions, which were eagerly taken up by the panelists: Eyal Weizman and Christina Varvia of the UK’s Forensic Architecture (FA); Bess Lee of Taiwan, a member of the civic tech community g0v, which aims for a complete rethink of the role of government; artist Ai Hasegawa, who engages with speculative art; fashion designer Kazuya Kawasaki; and architect Taichi Sunayama. What follows is a recap of the forum and thoughts on the potential of, and issues facing, art in the post-open data age.

Let us start with FA, a research agency based at Goldsmiths, University of London and centered on Israeli-born architect Eyal Weizman. Composed of some 21 experts in fields as diverse as architecture, art, filmmaking, journalism, science, archaeology, software development, and law, the agency was established in 2010 and has worked with human rights organizations including Amnesty International, Human Rights Watch, and B’Tselem as well as with the United Nations to conduct thorough forensic investigations into political violence and crimes against humanity perpetrated by state actors.

FA has investigated and solved a number of major cases, including accusations of border authorities’ killing of demonstrators, torture and killings at Syria’s Saydnaya Prison outside Damascus, and incidents involving vulnerable refugees in the Mediterranean.

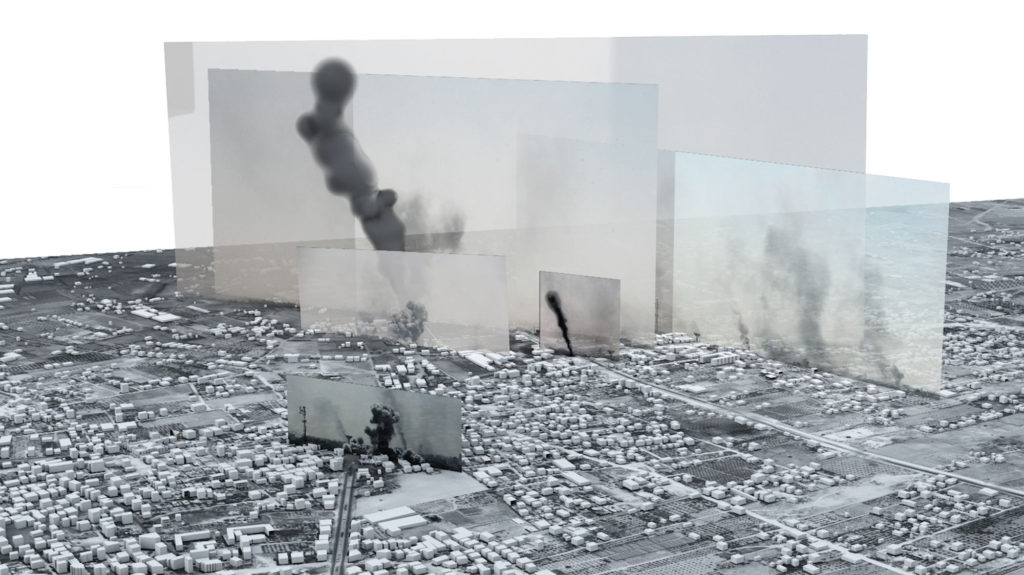

“Multiple images and reconstructed bomb clouds are arranged within a 3D model of Rafah, Gaza” ©FORENSIC ARCHITECTURE, 2019

The most distinctive part of FA’s activities is the group’s methodology. They use the vast variety of information available on social media. Looking at the remains of buildings destroyed in natural disasters, terrorist attacks, or war, the group analyzes the countless photos and videos taken of such buildings by professional and amateur photographers alike, taking into account things like blur and the positions of the sun, clouds, and shadows. This is done to pinpoint the time and place that each photo and video was taken in, thereby reconstructing the timeline of an event. Just as traumatic events tend to be erased from one’s memory, blanks tend to emerge “in between” the sources of different images. By investigating and reconstructing these blanks, FA uncovers truths distorted by governments, silenced voices, and the perpetrators of violence.

Let us look at an investigation brought up by FA Vice-Director Christina Varvia. In August 2014, the city of Rafah in Palestine suddenly came under attack despite a humanitarian ceasefire agreement being in place. The joint team established by FA and Amnesty International was not allowed to investigate on site. Instead, FA went about analyzing several hundred videos of black smoke rising in Rafah, procured from satellite broadcasts, professional journalists, and citizens on the ground. The group calculated the locations that had been bombed and those from which the videos had been shot. They built a so-called image complex, a 3D model of the entire city, and incorporated witness testimony gathered by Amnesty International to determine what had happened. FA also revealed how the shape of the bombs used in the attack indicated that they were American-made.

Christina Varvia (Forensic Architecture) photo by Shimpei Shimokawa

Of course, not all events are recorded and shared on social media. For example, abuses in Saydnaya Prison take place behind closed doors and are notoriously difficult to recreate by relying on the recollections of former prisoners. In such cases FA uses an interview method known as situated testimony, in which they build a space and research sound to recreate the situation as it happened.

This is how “truths” constructed with video, sound, maps, and the physical properties of the scene are turned into vivid evidence that is admissible in a court of law. This method, which Taro Igarashi calls “the architecture of information,” can prove that violence was committed by relying not only on human testimony but also on “truths” told by things that have been reduced to rubble [1]. It puts human rights into practice by taking the methodology of forensic inquiry from those in power and returning it to the people.

Interestingly, FA discloses this process not only in courts but on multiple platforms that include art museums and their website. The group thereby makes its evidence political, connecting it with “reality” as part of a struggle or an act of resistance.

According to Weizman, “art is not only a license to fictionalize. That the aesthetic practices could be very useful, but that there is things that we can do with the very basic tools and techniques that we have as architects, as filmmakers, as artists. The software that we all have on our laptops could be very powerful tools in confronting state and government lies.” [2]

Eyal Weizman (Forensic Architecture) photo by Shimpei Shimokawa

The big data collected by states and corporations in our modern-day “metadata society” becomes a resource, and meta-analysis of the data is employed to map our behavioral patterns and trends and to make predictions. Fragments of information become sources for algorithm administration.

FA, on the other hand, combines the mixed iconography of mass media, social media, satellite photographs, and more with on-site information such as wind direction, sounds, and shadows in a bricolage to get to the truth. This practice is made possible by information as a common good and a bricolage of knowledge based on that information. In that sense, what FA is doing is an example of “the architecture of information” in the form of a truth-seeking process, and therefore art.

Democracy and information as a common good

The questions of how open data is used and by whom are engaged on a more everyday level by g0v, a community that was established in Taiwan in 2012 and has already brought about an array of changes in society.

Founded on the openness of information and a spirit of freedom, g0v is a civic tech community that consists of free and decentralized grassroots networks of programmers, designers, activists, educators, writers, and engaged citizens. Their motto is “Be a ‘Nobody’,” meaning that instead of asking “why is nobody doing this,” one should be that “nobody.” Many of their methods are said to have been adopted by the Umbrella Movement in Hong Kong [3].

Bess Lee (g0v) photo by Shimpei Shimokawa

The activities of g0v were thrust into the spotlight in 2014, when the Sunflower Student Movement emerged in Taiwan. The group broadcast a live online stream from the occupied Legislative Yuan building, attracting widespread attention. Their g0v Summit, which has been held every two years since 2014, is now attended by civic tech communities from more than a dozen countries and attracts almost 1,000 participants, providing for a lively exchange of opinions.

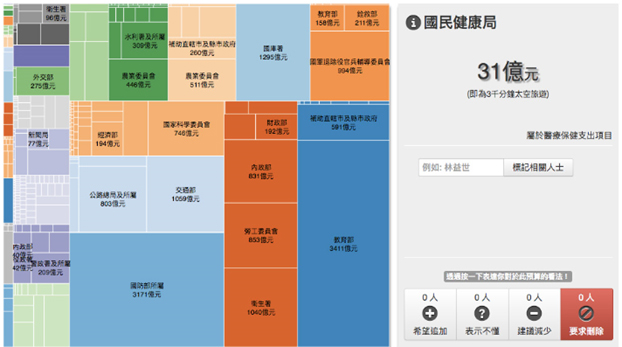

g0v is distinguished by its thorough dedication to transparency and the freedom of information. Bess Lee, one of the community’s chief staff members, mentions the “Government Budget Visualization” website as a major impetus for the establishment of g0v. This site was set up as a response to the gap between government policy and public sentiment perceived after the release of an advertisement promoting the Taiwanese government’s “Power-Up Plan for the Economy” in 2012.

No matter what country one looks at, the government budget tends to be an overwhelmingly thick document from which it is difficult to make out how public money actually gets spent. These challenges were overcome by presenting the budget in visual form, indicating tax revenue and expenditure as well as budget data with easy-to-understand design elements and practical comparisons, such as how many servings of pearl milk tea a certain sum equaled. By making government data transparent and shareable—“translating” it into a more approachable form, so to say—the project sought to provide a platform for democracy [4].

Comparing this to today’s politics in Japan, one begins to wonder who responds to criticism of the government and doubts about its policy and how, and whether citizen responses leading to storms on social media aggravate social division and cause a retreat into cynicism.

“Government Budget Visualization” CC BY g0v.tw

In any case, g0v enjoys a very high rate of participation. This fact is evidenced by the “Digitalization of Political Donations” project, for which civic hackers went through 30,000 documents in only 24 hours. And in 2016, g0v established g0v Civic Tech Prototype Grant as part of its pursuit of infrastructure systems that would allow the community to sustain itself into the future.

g0v projects (known as “shafts” or “forks”), which aim for thorough government disclosure and transparency and are debated at regular meetings, take the form of so-called hackathons (so named because participant numbers rival those of marathons) that are sustained by an open community. The group is above all an open, grassroots civic tech community, and not all of its projects are successful. Its hackathon approach, however, allows previously discontinued projects to be taken up again by new participants, as often happens.

In August 2016, g0v’s Audrey Tang was invited to join the cabinet of Premier Lin Chuan as Digital Minister in the Executive Yuan. Tang employed g0v’s approach when setting up vTaiwan, a consultation process intended to encourage online participation. The platform sees debate on a wide range of issues, including the use of Uber and self-driving cars. Audrey Tang seeks to promote digital democracy and patch up the weaknesses of representative democracy by having citizens serve as a check on government, while g0v functions as a community open to anyone that facilitates debate and upholds the political decision-making process.

photo by Shimpei Shimokawa

Art that ponders the future and questions the present

If FA and g0v’s use of highly diverse networks to produce new critical insights and bring about social change is considered an artistic practice, then “speculative art” should be seen as the pursuit of an alternative society from a different point of departure.

Ai Hasegawa is an artist who embodies this approach. Her richly suggestive works include “I Wanna Deliver a Dolphin” (2011-2013), in which she took on the role of mother to an endangered dolphin species, and “(Im)possible Baby, Case 01: Asako & Moriga” (2015), an exploration of whether a child can be born to two people of the same sex. Hasegawa’s projects also start with doubts directed toward the decision-making processes of state and society.

She engages with questions such as why the guidelines concerning single motherhood vary from country to country, and how and by whom the ethical barriers that prevent same-sex couples from having children are constructed.

Ai Hasegawaphoto by Shimpei Shimokawa

Hasegawa focuses on the biases hidden in seemingly obvious value judgments. Based on questions of bias, her artworks paint a picture of a virtual future rich in speculation. These works appear to be platforms for future-oriented debates.

“Alt-Bias Gun” is one example. Created as a response to the racial discrimination Hasegawa felt while living in the United States, it incorporates facial-recognition technology that has been conditioned to distinguish the kinds of people most likely to be shot by mistake. When a person with such a face stands in front of the gun’s barrel, its trigger is locked for three seconds. Turning an existing bias on its head, the piece was created to prevent innocent black people from being shot to death; an alternative option, so to speak. Standing up against the dystopia we imagine when artificial intelligence, guns, and the government come together, it is an effort to rethink the reproduction of human prejudice and its latent propagation in the form of AI bias.

Ai Hasegawa《Alt-Bias Gun-Black Lives Matter Version-》(work in progress)

Another approach is taken by fashion designer Kazuya Kawasaki, who focuses on the unequal relationships between the human and the non-human. His work ponders the natural environment from the perspectives of biotechnology and artificial intelligence, while architect Taichi Sunayama engages with algorithms and design computing.

Their book “Speculations: Beyond Human-Centered Design” highlights a diverse range of ideas and practices for social change from a post-human-centered point of view [5]. Among the most interesting of these are projects such as “Biological Tailor-Made,” in which garments are fashioned from material created by bacteria, and “Algorithmic Couture,” which uses an algorithm to eliminate fabric waste. Both of these are based on a reordering of the relationships between organisms in the natural world and non-human elements in the world of information, such as data and algorithms. Thought up by Kawasaki, these initiatives are inquiries into new possibilities in fashion and environmental design.

All of these efforts are opportunities to readjust the social inequalities hidden in the current media ecosystem itself. They seek to engage our senses, and to shake our “emotional ordering” of public matters.

Kazuya Kawasaki photo by Shimpei Shimokawa

Taichi Sunayama photo by Shimpei Shimokawa

The forum, which went on for about five and a half hours, brought to light once again political questions concerning freedom and equality in the age of digital media.

Technology, while useful, sometimes robs us of the opportunities to think. The efforts of the artists described here go beyond simple proclamations of technical determinism that predict developments in media leading to a new politics, a new society, a new culture. Instead, they address urgent questions such as how capitalism extends its grip in the age of social media, and how developments in digital media transform the relationships between politics, the economy, and the media. They also provide society with an ecology of the commons as a strategy for escape, and present alternative options for the future.

photo by Shimpei Shimokawa

Equality for everyone is considered a precondition in our understanding of democracy, but the reality is different. If disagreement is understood in the terms of Jacques Rancière (“a situation when one of the interlocutors understands and does not understand the other at the same time”), politics begins only when the reality of unequal distribution is revealed and existing systems, previously seen as stable, begin to show cracks—when true equality is achieved. In this sense, the practice of media art is truly an act of politics itself [6].

When one considers modern-day Japanese politics, where “truth” can be presented as anything one wants it to be and lies are accepted one after the other, all in pursuit of private interests and pleasure or in a calculated charade that plays to the audience’s expectations, the things that can be learned from these artistic practices appear unlimited. The act of bringing back the commons to today’s closed, divided society, and art, which springs forth from the things and people left behind by dominant forces in society—these efforts open up horizons with such social significance that they fully deserve both public support and a rethinking of the very value of such support.

In the early 1990s, the French philosopher Félix Guattari spoke of his hope for a “post-media” era, in which mass-media power that crushes individual subjectivity would be interactively reappropriated [7]. Even then, this hope seemed somewhat optimistic. However, 30 years later, when the echoes of the phrase “There Is No Alternative” ring with urgency, the vision, updated and passed on, feels both old and new—it feels like something to pursue for the sake of the future.

Notes

[1] Taro Igarashi, “Forensic Architecture—jiken no kenchiku wo saigen suru (Recreating the architecture of a crime),” Gendai Shiso, March 2018 Special Issue. General Feature. Gendai wo ikiru tame no eizo gaido 51. Seidosha, 2018.

[2] Forensic Architecture, Turner Prize Nominee 2018, Tate Shots, https://www.youtube.com/watch?time_continue=3&v=_-yQ__UK€sl161€slmult0 €sl161€slmult0

[3] g0v website: https://g0v.tw/en-US/

[4] Lung, Pei-ning & Liu Yingfeng, In Pursuit of Open Government: Civic Hackers of the g0v. Taiwan Panorama, August 2017. Translated by Yukina Yamaguchi. https://www.taiwan-panorama.com/ja/Articles/Details?Guid=71c2e863-595c-4b39-849c-c260c0f3e5a0&CatId=7

[5] Kazuya Kawasaki (ed.), Speculations: Beyond Human-Centered Design. BNN, Inc., 2019.

[6] Jacques Rancière, Disagreement: Politics and Philosophy. Inscript, 2005. Translated by Shoichi Matsuba, Hidetomi Omori, and Shigeo Fujie.

[7] Felix Guattari, “Towards a Post-Media Era,” Provocative Alloys: A Post-Media Anthology, PML Books: Leuphana, 1990=2013.

INFORMATION

Forum for Social Practice in Art/Media ‘Cultural Resistance in the Post-Open Data Age’

Date: 2019.12.15

Venue: 1F Hall, Tokyo Photographic Art Museum

Organized by Arts Council Tokyo (Tokyo Metropolitan Foundation for History and Culture)