Born in Aichi. Associate professor at the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences, Tsukuba University, specializing in media and cultural theory. Publications include Culture and Violence: The Unravelling Union Jack(Getsuyosha), Community-Engaged Art Project(joint authorship, Horinouchi Publishing), Art and Labour(joint authorship, Suiseisha), and Towards the 21st Century Philosophy(joint authorship, Minerva Shobo). Translations include Judith Butler, Notes Toward a Performative Theory of Assembly(co-translation, Seidosha) and Antonio Negri & Michael Hardt, Declaration(co-translation, NHK Publishing).

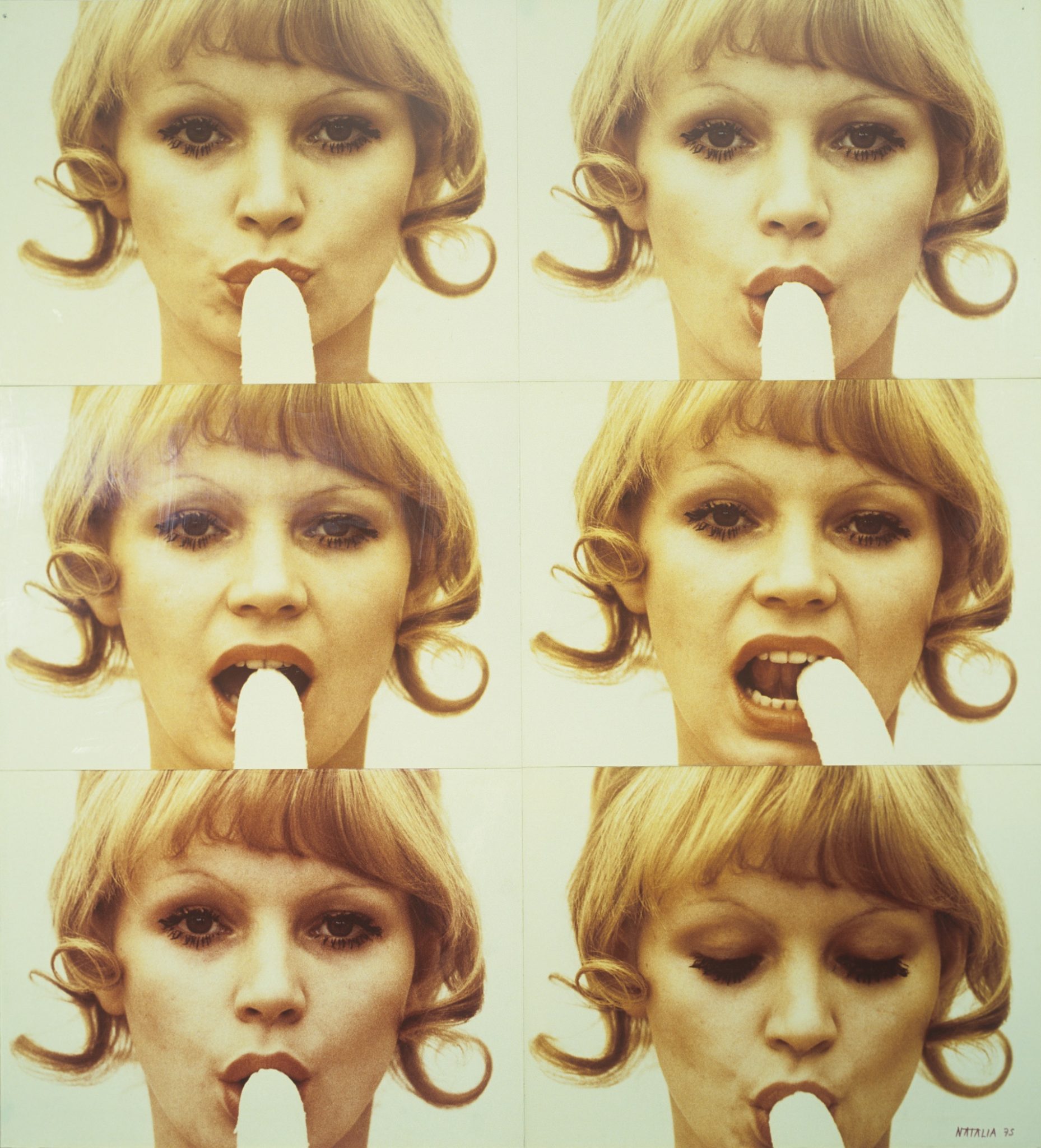

Natalia LL, Consumer Art, 1972 ©Natalia LL / Courtesy of lokal_30 Gallery, Warsaw

On April 29, 2019, a big demonstration of people eating or holding bananas took place in front of the National Museum in Warsaw. The demonstrators protested against the museum’s plans to remove Natalia LL’s work “Consumer Art” (1972) because it “might provoke sensitive young people.”

Photographs of naked women eating or licking bananas may in fact be seen as metaphorical expressions with a sexual notion, but in the case of this work, it was more about “consuming” bananas that were a luxury article at the time, and at the same time, it was a pioneering work of feminist art opposing the conservative society by linking consumer activities to sexual motifs. I ask myself what kind of age this 21st century is, with artworks that have been exhibited under the communist system getting censored.

The “Her Own Way – Female Artists and the Moving Image in Art in Poland: From 1970s to the Present” exhibition that is currently showing at the Tokyo Photographic Art Museum illustrates the changing currents of female art in Poland against the backdrop of drastic changes in their country over the past fifty years.

In the Cold War era in the 1970s and ’80s, Poland was right in the middle of censorship in the form of prohibition of public assembly and strictly limited access to videos and cameras among others. After the revolution and subsequent democratization in Eastern Europe, Poland is currently entangled in various currents including a debate on the ban of abortion and related censorship of depictions of nudity, as well as radical rightist and anti-gender movements. Now how have female artists been using art as a weapon in their “fight” against these circumstances?

According to curator Keiko Okamura, there have been very few exhibitions focusing on female artists in Poland up to now. In the pre-democratic times in particular, the works and achievements of female artists have been documented only fragmentarily, and their situation is devastating. As a matter of fact, there are activities underway also within Poland with the aim to shed light on the buried history of female art in the country, and rescue the endeavors of female artists. While zooming in on Polish art history as a current subject of reconsideration, this ambitious show aims to highlight the new and diverse artistic styles explored by a new generation of artists in post-democratic Poland, especially after 2000.

Now there may be people who feel somewhat irritated by the use of the “female artist” label in the 21st century. But it was in fact in 1971 that Linda Nochlin asked, “Why have there been no great women artists?”

In 1978, Natalia LL organized the exhibition “Woman’s Art: Suzy Lake, Noemi Maidan, Natalia LL, Carolee Schneemann” (Galeria PSP Jatki, Wrocław) the first exhibition of feminist artists in Poland, with the aim to spread feminist thinking in the country. In Japan, the first exhibition at an art museum that was based on viewpoints related to feminism and gender was the “Exploring the Unknown Self: Self-portraits of Contemporary Women” show in 1991. With the global #Me Too movement, Roxane Gay’s Bad Feminist, and a Korean novel, Kim Ji Young born 1982 that has become a best-seller also here in Japan, there are some new developments in feminism right now. Looking at the situation against this backdrop, it seems that are still in the middle of a transformation toward a world in which we no longer need to carry the “woman” banner in the first place.

In this respect, the medium of “moving image” that is at once the second keyword of this exhibition takes on particular significance. In the 1970s, there was a general supply shortage in Poland, and the state kept implementing measures of political censorship. Not only were cameras hardly available to anyone – man or woman – but as this exhibition’s co-curator Marika Kuźmicz points out, the realms of avant-garde art and experimental film were firmly in male hands since the interwar years, and even in the 1960s-70s, women were “systematically excluded” from the world of art. The women who managed to get hold of a camera belonged to a generation of female artists that were the first to be able to work with the same media and operate on the same ground as men, and through film – not video – they engaged in political activities that were in no way inferior to those in the West.

However, to lump it all together under the category of “film” would mean to miss quite a lot of points, as styles and strategies are truly multifarious. Rather than language, artists have been employing in their critical statements metaphors rich in humor and irony that are open to varied interpretation, in order to escape the state censors. Akiko Kasuya, a researcher in the field of Polish art, calls it “applied fantasy.”

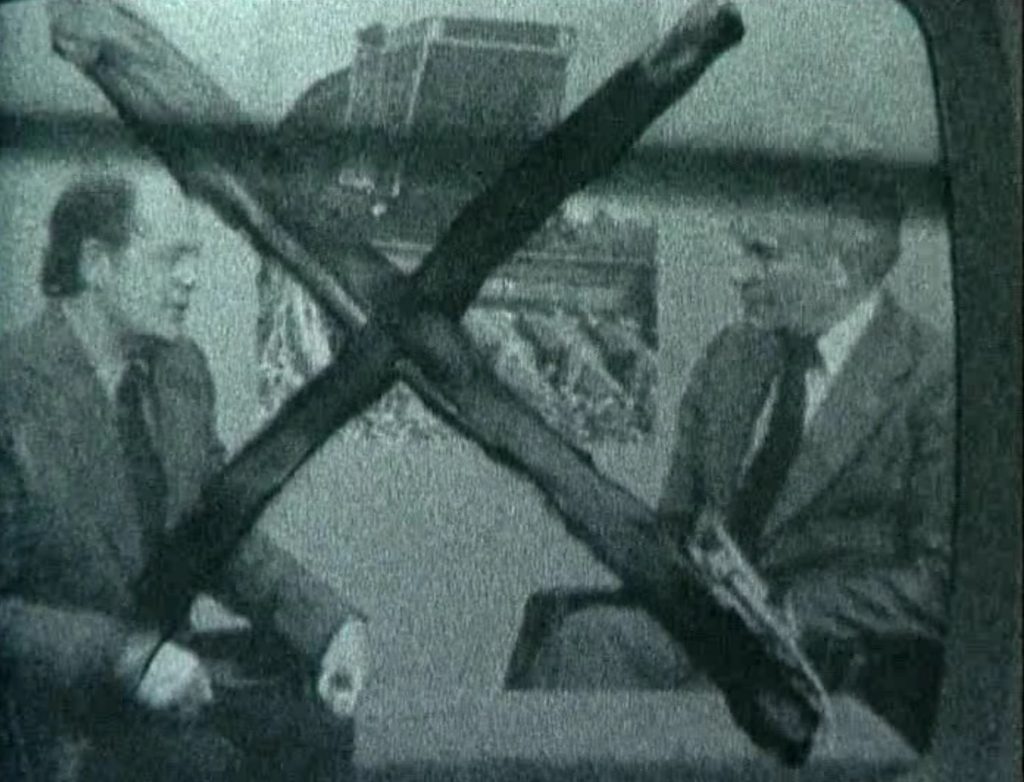

Ewa Partum, Drawing TV, 1976 Courtesy of the artist and Arton Foundation, Warsaw

Anna Kutera, Dialog, 1973, Courtesy of the artist

In the 1970s, Ewa Partum, a pioneer of feminist art, presented “Drawing TV” (1976). A TV in the artist’s room showed propaganda films of Polish communist party leaders, with a large “X” written across the screen as an expression of severe criticism against messages from the powers that be from within a private space – a style reminiscent of Asger Jorn’s détournement of paintings. Elsewhere, Anna Kutera goes for her work “Dialog” (1973) out into urban spaces and asks passersby for a street named after herself: “Where is Anna Kutera street?” Her question is at once a questioning of the real-life situation of public spaces being increasingly privileged and masculinized. The streets of Wrocław, which also served as a movie set, are in fact full of famous male artists’ names, but not a single one of them is named after a woman.

Julita Wójcik, Peeling Potatoes, 2001, Collection of Zachęta – National Gallery of Art, Warsaw

In response to this pioneering generation of the 1970s, Poland after the 1990s saw the rise of the “critical art” generation of artists who investigated the era of communism while at once exploring possible ways into the future. Wearing an apron on top of her old-fashioned everyday clothes, Julita Wójcik takes the entire operation of a woman doing what she “has always been supposed to do” – peeling potatoes in the kitchen – to the museum as a piece of art. The video capturing that performance, “Peeling Potatoes” (2001) challenges the conventional meaning of “art” and its arena by crossing private and public spaces in the sense of Hannah Arendt’s politics of “appearance.”

Joanna Rajkowska, Basia, 2009 Courtesy of the artist and l’étrangère Gallery, London photo: Marek Szczepański

Joanna Rajkowska’s video “Basia” (2009) captures a guerilla style performance in which the artist relives her own mother’s experience escaping from a hospital as a dementia patient roaming about before dying one year earlier, along with people’s reactions. Wearing make-up to look like an old woman, and dressed in the hospital’s pajamas, Rajkowska wanders around like a ghost, but with some people’s help she eventually “returns” to the closed institution of the hospital. In the looped video in which she roams about and is taken to the hospital again and again, the artist becomes her mother as she got isolated from society, marginalized, and eventually died. At the same time, however, the looped playback also hints at the daily routine of women in socialist era Poland, who went out to work at factories from where they had to return home again immediately.

Zuzanna Janin, Fight, 2001 Courtesy of the artist and Lokal_30, Warsaw

Karolina Bregula, Ah Professor!, 2018, Courtesy of the artist

In “Fight” (2001), Zuzanna Janin faces a heavy-weight male professional boxer and thoroughly withstands the masculine power, while Karolina Breguła keeps shouting “Oh, Professor!” in her 2018 video with just that title, demanding liberation from the system of art education that is completely devoted to male instructors, including the artist’s own charismatic professor back when she was an art student. As an essential characteristic that all of these works share, the respective artists make themselves the subjects of their works, while at once performing in front of the camera as objects.

But these videos in which female artists present themselves differ greatly from the “self-portraits” in which male artists used to depict themselves, and can rather be understood as proposing various antitheses to those.

Katarzyna Kozyra, Punishment and Crime, 2002, Courtesy of the artist

Now let’s take a look at Katarzyna Kozyra’s “Punishment and Crime” (2002), a “video version of a combat game” in which weapons are used to blow up heavy machines and vehicles on a vacant piece of land. The faces of the participating men were replaced with masks of female pin-up models, reversing the formulaic traditional image of “men” as defined through aspects of militancy, violence, and an urge to destroy, and the image of porn actresses, on an expanded stage of representation and interpretation.

Karol Radziszewski, Karol and Natalia LL, 2011, Courtesy of the artist and BWA Warszawa, Warsaw

As curator Okamura emphasizes, the exhibition was not at all put together “for women only” or as a show that “excluded out of mischief works by male artists.”

Karol Radziszewski, the first artist in Poland who openly acknowledged his homosexuality, discovered Natalia LL’s work when he was looking for a role model for himself as a queer artist. In his documentary film “America Is Not Ready For This” (2012), however, Radziszewski not only discusses gender politics, but provides also highly suggestive clues regarding the underlying art and culture of the Cold War era at large.

Based in New York in the late 1970s, Natalia LL worked at once as a bridge between the east and the west. In order to find out how she was accepted in New York at the time, interviews were conducted with Natalia herself, as well as people who were familiar with her work, such as Vito Acconci, Carolee Schneemann, Douglas Crimp and Marina Abramovic. Regarding the “eastern banana” in the form of Natalia LL’s “Consumer Art” in relation to the western banana in the form of Andy Warhol’s “Mario Banana” (1964), the mic is passed also to performer Mario Montez.

The core element of the film, however, is a comment from art dealer Leo Castelli. No matter how hard Natalia tried to socialize, her works would not get exhibited in the USA, which Castelli blames on the fact that “America was not ready for this.” In regard to this comment, the discrepancies in the interpretations of such matters as feminism and queers in the realms of eastern and western art become obvious. The most ironic thing here is that the closed nature of New York, which was at the time synonymous with the cutting edge of art, gets perfectly revealed. “America wasn’t ready” means that, not limited to Natalia’s work alone, the American art world itself wasn’t prepared at all for feminism and feminist art, even though the likes of Bonnie Ora Sherk, Mierle Laderman Ukelesor and Suzanne Lacy had already been creating all kinds of political art in the States.

Agnieszka Polska, Ask the Siren, 2017年 Courtesy of the artist and ŻAK | BRANICKA, Berlin

Now all this doesn’t necessarily mean that everything is wonderful in Poland in the 21st century. It’s the new generation of artists who remind us of the deadlock situation.

Agnieszka Polska’s “Ask the Siren” (2017) reexamines the nature of Poland as an assailant. Here the ancient Eastern European legend of sirens, which also inspired the well-known symbol of Warsaw, overlaps with the history of the country that was established at a time when non-Christians were expelled as heathens. Through dialogues between two female figures somewhere between human and mermaid, memories of past bloodshed are revived and hover through the streets like ghosts swimming in the water. Created by way of computer graphics, the “mermaids” turn into grotesquely cute monsters that represent the stifling situation in contemporary Poland with increasing calls for the expulsion of immigrants.

Jana Shostak, 2017, Courtesy of the artist (Photo: Nowak)

Jana Shostak, who immigrated to Poland from Belarus, and thus lives in Poland as a foreign resident, has been using social media and selfies in her numerous previous challenges at hacking the established system. She made clear that the Polish word for “refugee” is in fact an expression that is distressing for actual refugees, and proposed to replace the term with the new word “nowak” (literally “a newly arrived person”). She also participates in “Miss” contests around Poland, and actively appears in the mass media, and is currently working on the documentary “Miss Polonii” (to be completed in 2020), in which she takes the viewer on a backstage tour around the world of beauty pageants, from an insider’s point of view.

This new generation of artists challenge the closed nature of Poland as a nation, and different from both the generation of pioneering artists in the ’70s, and from the “critical art” generation from the ’90s onward, they radiate a unique kind of lightness and power. As Agnieszka Rayzacher writes in her essay in the exhibition catalogue, however, manifested here is a succession beyond ages and techniques of the thorough artistic mindset of consistently asking, “If not me, who? If not now, when?” (Emma Watson).

The variety and density of strategies introduced through the works featured in this exhibition, along with the artists’ constant struggles, will surely provide us with valuable hints as to how to relieve the distressful situation of the “crisis” we face right now in our so-called “democratic nations” without an exit in sight.

INFORMATION

Her Own Way - Female Artists and the Moving Image in Art in Poland: From 1970s to the Present

August 14 - October 14, 2019

Organized by Tokyo Metropolitan Government, Tokyo Photographic Art Museum and Nikkei Inc.

Specially supported by Adam Mickiewicz Institute / Culture. pl

With assistance from Polish Institute in Tokyo

Sponsored by Toppan Printing Co., Ltd.