Hiroki Yamamoto, born in Chiba in 1986, is Lecturer at Kanazawa College of Art in Japan. Yamamoto graduated in Social Science at Hitotsubashi University, Tokyo in 2010 and completed his MA in Fine Art at Chelsea College of Arts (UAL), London in 2013. In 2018, he received a PhD from the University of the Arts London. From 2013 until 2018, he worked at Research Centre for Transnational Art, Identity and Nation (TrAIN) as a postgraduate research fellow. After working at Asia Culture Center (ACC) in Gwangju, South Korea as a research fellow and The Hong Kong Polytechnic University, the School of Design as a postdoctoral fellow, he was Assistant Professor at Tokyo University of the Arts until 2020. His publications include The History of Contemporary Art: Euro-America, Japan, and Transnational (Chuo Koron Sha, 2019), Media and Culture in Transnational Asia: Convergences and Divergences (Rutgers University Press, 2020), and Thinking about Racism (Kyowakoku, 2021).

Ho Tzu Nyen, Character Design: Kitsune, “Night March of Hundred Monsters” 2021

Engaging with Japanese imperialism through art

An online lecture by Ho Tzu Nyen, titled “Monsters and Aporias: Engaging with Japanese Imperialism through Art” and organized by Tokyo University of the Arts, was held on December 10, 2021. Ho is an internationally active, Singapore-based artist and filmmaker. Curator Natsumi Araki, an associate professor at the university, moderated the event, which was open not only to students and faculty but also to people outside the university. The lecture attracted a large number of attendees from both inside and outside the university, indicating the high level of interest there is in Japan in Ho Tzu Nyen as an artist. At the same time, the turnout for the lecture highlights how interest in the subject of the complicity between culture and imperialism is growing in this country. This is exactly the kind of dynamic that Ho has sought to address in his recent works.

There’s no doubt that the growing interest in this topic in the field of contemporary art is a phenomenon occurring in the matrix of relations between wartime Japan and other Asian countries (including Ho’s birthplace, Singapore). This phenomenon can be seen to include Hong Kong media artist Royce Ng’s solo exhibition “The Death of Manchuria…Is the Prerequisite for the Birth of Post-War Asia,” held in the summer of 2021 at Asakusa, an alternative venue in Tokyo. That exhibition featured two of Ng’s video works themed on “the legacy of Manchukuo (the puppet state of imperial Japan established in northeastern China in 1932) in East Asia”: “Kishi the Vampire” (2016) and “State Alchemist I: Body without Organs” (2021). One would guess that Araki’s intention in organizing Ho’s lecture this time was to create an opportunity to think deeply, “through art,” about historical issues related to other Asian countries rooted in Japan’s imperial past by discussing them, including with students, in a university/academic setting.

As mentioned earlier, there are notable similarities between Ho’s and Ng’s artistic practices (e.g., being from a place once occupied by Japan, and having an interest in the intersectional space between wartime imperial Japan and culture and thought). For this reason, I believe it is essential to analyze the two comprehensively as a subset of a single phenomenon. However, it is also clear that there’s risk involved in a simple juxtaposition of the works of these artists, which differ in style and approach. *1 In this sense, this event, where Ho himself was present to discuss his work in depth, can be considered highly significant.

Ho presented the installation “Hotel Aporia” (2019) at Aichi Triennale 2019. It attracted attention by being displayed in the building that once housed the Kirakutei, a restaurant and inn where, during World War II, members of the Tokkotai (“Special Attack Unit” aka Kamikaze, the military aviators who flew suicide attacks in the Pacific War) spent their final nights. In 2021, he created “Voice of Void” (2021), a video installation that combines virtual reality (VR) and animation elements, and in the same year he held a solo exhibition with the same name at the Yamaguchi Center for Arts and Media (YCAM). Ho’s latest video installation, “Night March of Hundred Monsters,” is composed mainly of animation and was prepared for his solo exhibition at the Toyota Municipal Museum of Art, held from the end of 2021 through to early 2022. That exhibition proved a resounding success, transcending the borders of the narrowly defined “art world,” including through a conversation between Ho and the thinker Hiroki Azuma (“Genron Cafe,” October 25, 2021) that was held to celebrate the exhibition’s opening. The works all shed light on the effect (and reverberations) of wartime Japanese imperialism on other Asian countries, and on its complicity with culture and ideology. The Tokyo University of the Arts lecture featured Ho’s own commentary on these works.

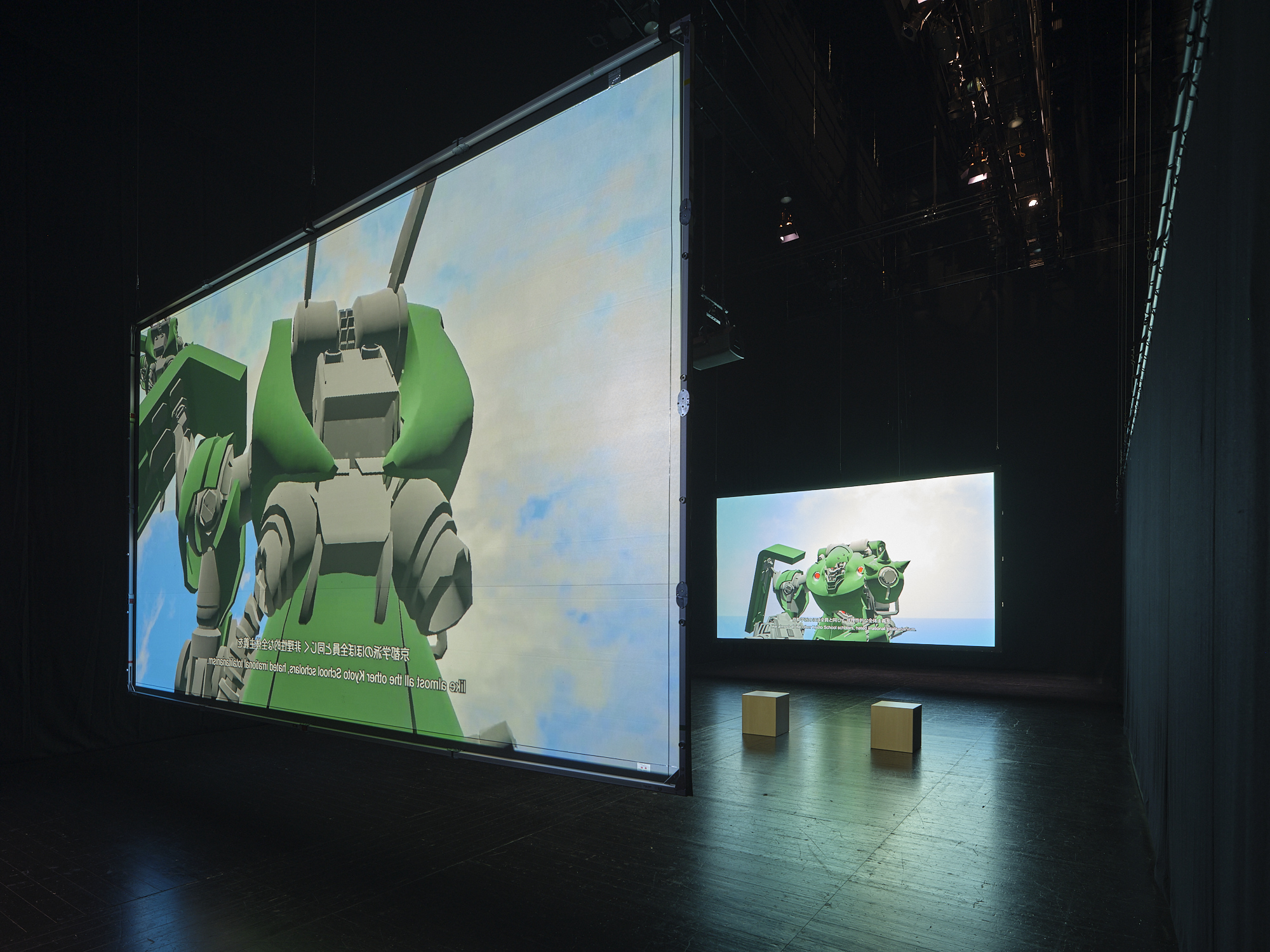

Installation view of “100 Monsters,” from Night March of Hundred Monsters, 2021

Photograph by Hiroshi Tanigawa, courtesy of Toyota Municipal Museum of Art

Ho Tzu Nyen, Character Design: Tiger of Malaya,“Night March of Hundred Monsters” 2021

Asia as method

Ho opened with a commentary on “Hotel Aporia,” which marked the beginning of his series of works on imperial Japan. He pointed out the constraints he had to deal with in exhibiting in the historical building that once housed the Kirakutei, such as not being able to make holes in any part of the structure, and then, referring to an anecdote in Junichiro Tanizaki’s “In Praise of Shadows,” laid out a practical method of constructing the exhibition that rather made the most of said constraints. Understanding this creative process is meaningful not only for curators and researchers who are interested in Ho’s activities, but also for actual artists, including students learning practical skills.

Using the viewer’s perspective created by the exhibition’s composition as a point of departure, Ho focused on Yasujiro Ozu, who was sent to Singapore during the war to shoot a propaganda film. From there, his vivid imagination organically linked such figures as Yukiko Nagasaka (a former proprietress of the Kirakutei restaurant), Sakae Miyauchi (a lieutenant in the 3rd Kusanagi Corps of the Navy Special Attack Unit), Ryuichi Yokoyama (a cartoonist sent to Indonesia as part of a propaganda unit), and philosophers of the Kyoto School who advocated Asianism. These people were all invited as “guests” to the Hotel Aporia. The various voices of these guests, who were not necessarily connected to each other in any explicit sense but who all lived through Japan’s difficult wartime period, were spun together to produce polyphony, harmony, resonance, and dissonance. Ho said that the space created by Hotel Aporia was conceived as a place filled with all these elements.

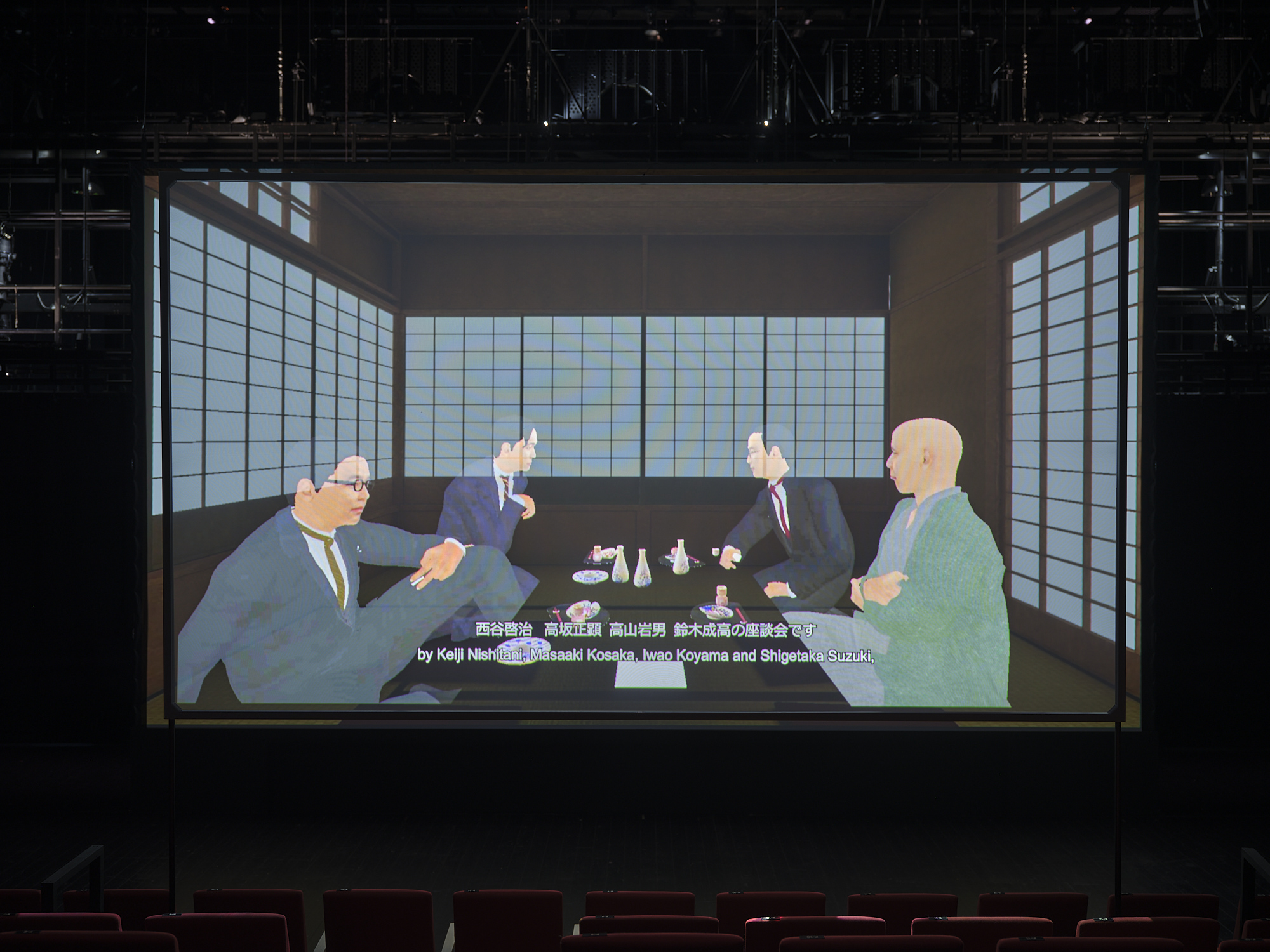

Ho then moved on to discuss his second artwork, “Voice of Void.” This work focuses on the philosophers who formed the “Kyoto School” in the broadest sense of the term, such as Kitaro Nishida, Hajime Tanabe, Keiji Nishitani, and Kiyoshi Miki, and engages with their ideas—which are often said to have provided the rhetoric that justified Japan’s imperialism during the war—through art.

The standout feature of this work is the use of VR technology. Aesthetics researcher Futoshi Hoshino takes up “Voice of Void” in his latest paper, “VR and the State” (2022), focusing on the technology’s powerful identification effect. He points out that a “call to action” in the unique space it provides is parallel to the very “foremost technology of the state” that encourages uncritical unification of the self and the state (i.e., the disappearance of the individual and subjectivity under totalitarianism), as observed throughout many of the statements of Kyoto School thinkers at the time, including Hajime Tanabe’s “Life and Death” lecture, which is said to have greatly contributed to the mobilization of students for war. *2 This point is also related to the overwhelming power of VR and animation in Ho’s works and the strange “comfort” it brings, as Araki pointed out in the latter half of the lecture. Of course, Ho himself is conscious of such structures and deliberately creates spaces with such intensity. In the lecture, he explained in detail the methodology of integrating VR technology into his video installations.

Finally, the artist himself explained his latest artwork, “Night March of Hundred Monsters.” As Ho emphasizes, the multifaceted composition of the work, which consists of four exhibition rooms—“One Hundred Monsters,” “Thirty-six Monsters,” “One or Two Spies,” and “One or Two Tigers”—shares similarities with “Hotel Aporia” and “Voice of Void.” Ho says that its main theme, foregrounded by the humorous characters based on yokai motifs, is the “strange entanglement between religion, violence, and nationalism” surrounding imperial Japan.

The concept of “Asia as method” kept coming back to my mind throughout the event. That idea emerged from an eponymous lecture given by Yoshimi Takeuchi, a scholar of Chinese literature, at International Christian University in the early 1960s. In the lecture, Takeuchi suggested that a de-Westernized perspective was essential to dispel the residue of imperialism supported by colonial aggression, and that the concept of Asia as a “process of subject formation,” i.e. a “method,” rather than an entity, might be effective for this purpose. *3 In recent years, cultural scholars from East Asia, such as Sun Ge *4, Chen Kuan-hsing *5, and Koichi Iwabuchi *6, have built on Takeuchi’s proposal, each developing their own methodologies for overcoming the legacy left by Japanese imperialism.

The perspective that “the history of Japan during the imperialist era is no longer just the history of Japan alone, but is already part of the history of Asia as a whole,” stated by Ho during the Q&A session, truly expresses the ethos of “Asia as method.” In this sense, Ho can be described as an artist who is literally practicing “Asia as method” through his artistic work. The Q&A session with the participants, including the moderator Araki, was a stimulating one, with different angles and approaches on the legacy of Japanese imperialism presented from various standpoints, resulting in a dynamic process of collision, negotiation, and compromise between them. In this respect, “Monsters and Aporias: Engaging with Japanese Imperialism through Art” itself embodied the “Asia as method” approach.

Installation view of “Voice of Void,” 2021

Photograph by Ichiro Mishima, courtesy of Yamaguchi Center for Arts and Media [YCAM] and the artist

Questioning clear-cut concepts and unraveling the historical processes of their construction

On December 17, one week after the lecture, an online critique session was held with Ho invited as a guest. Current Tokyo University of the Arts students—Koken Arakawa, Shinobu Soejima, Ayae Kamiya, Rintaro Fuse, and Tomomi Oka—gave presentations on their artworks, and Ho responded with questions and comments. Natsumi Araki served as moderator, reprising her role from the lecture. The five presenting students are all already up-and-coming artists active outside of the university and with distinctive artistic approaches that have won each of them attention. I cannot here describe in detail the content of the hour and a half of dense presentations and critiques, but I was impressed by Ho’s sincere attitude of respecting all presenters equally as fellow artists, and responding with his own perspective and frank critical questions.

As Araki mentioned at the end of the session, Ho’s stance of thoroughly questioning concepts that are considered self-evident led to a mutually productive dialogue with the presenters. He asked what the notions we use in our daily lives actually mean; for example, “nature” for Arakawa, “light” *7 for Soejima, “society” for Kamiya, “face” and “rhythm” for Fuse, and “time” for Oka. The questions, which asked the presenters to redefine “self-evident” concepts one by one in their own way, encouraged deeper reflection in the presenters and seemed to give new insights into Ho’s own artistic practice as well (For example, when discussing the relationship between light and shadows, he overlapped Soejima’s animation with his own “Hotel Aporia”). Questioning the self-evidentness of all concepts appears to be at the core of Ho’s own artistic practice. *8 In addition, I was amazed by the richness of Ho’s insights, as his arguments incorporated a wide variety of references, including Akira Mizuta Lippit, Junichiro Tanizaki, Robert Rauschenberg, Deleuze and Guattari, and Michael Fried.

Kamiya, who is also a member of the artist collective Hito to Hito, introduced a video and installation work that uses her own traumatic experiences as a starting point to explore issues related to sexuality and gender. In response, Ho praised her method of re-presenting issues concerning sexuality as social rather than personal, while posing the question of “how these issues have been constructed historically.” The careful analysis of how a certain issue or phenomenon is constructed historically is also a distinctive characteristic of Ho’s own artistic practice. In a recent interview, he questioned the utility of the “reality/fiction” dichotomy in history, arguing that “fiction can also be productive in leading us to a better world.” *9 It appears that for now, “Night March of Hundred Monsters” will be Ho’s last work concerning wartime Japan, but I’m sure that he will continue to both engage with various issues brought about by history and, through art, to question concepts and dichotomies that we often take for granted. I am also very much looking forward to seeing how the presenters’ artistic practices will develop in the future after their encounter with Ho.

Installation view of “Hotel Aporia,” 2019

Photograph by Hiroshi Tanigawa, courtesy of Aichi Triennale 2019

1) This thought was inspired by a personal conversation with Jung-Yeon Ma, who specializes in film and media studies and contemporary art, and I would like to express my gratitude to her here.

2) Futoshi Hoshino “VR to kokka (VR and the State),” Bijutsu techo, February 2022, page 214.

3) Yoshimi Takeuchi “Nihon to Ajia (Japan and Asia).” Chikuma Gakugei Bunko, 1993. Page 469.

4) Sun Ge “Asia wo kataru koto no jirenma chi no kyodokukan wo motomete (The Dilemma with Discussing Asia: Pursuing a Shared Intellectual Space).” Iwanami Shoten, 2002.

5) Chen Kuan-hsing “Asia as Method: Toward Deimperialization.” Duke University Press, 2010.

6) Koichi Iwabuchi “Toransunashonaru Japan: Popyura bunka ga ajia wo hiraku (Transnational Japan: Popular culture opens up cross-border dialogue in Asia).” Iwanami Gendai Bunko, 2016. See especially “Trans-Asia as method: Media culture opens up Asia.”

7) Referring to the violence of the modern “enlightenment,” Ho raised the question of why “shadows” are often subordinated to “light.”

8) For example, the historian Jun Yonaha posits that Ho’s “Night March of Hundred Monsters” presents, in contrast to the existing understanding of “history,” i.e. “collective memory of society,” something like “a dream some person had at night and ‘recalls in solitude.” Jun Yonaha “The Interchangeable and the Unified Collective” from “Ho Tzu Nyen: Night March of Hundred Monsters” ed. Toyota Municipal Museum of Art. Torch Press, 2021. Page 275.

9) “Artist Interview: Ho Tzu Nyen (interviewer: Yoko Nose),” Bijutsu techo, February 2022, page 194.

INFORMATION

Lecture by Ho Tzu Nyen: “Monsters and Aporias: Engaging with Japanese Imperialism through Art”

Held online December 10, 2021