Architectural historian and critic, was born in 1967 in Paris. Professor at Tohoku University. Commissioner for Japan pavilion at the Venice Biennale of architecture 2008. Artistic director of Aichi Triennale 2013 Publications include “Contemporary Japanese architects : Profiles in design”, “Architecture and Music” etc.

SHIGA Lieko, “Waiting for the Wind: Tokyo Contemporary Art Award 2021-2023 Exhibition” installation view, Museum of Contemporary Art Tokyo, 2023 Photo: TAKAHASHI Kenji Photo courtesy of Tokyo Arts and Space

Wind/The Invisible/Marking

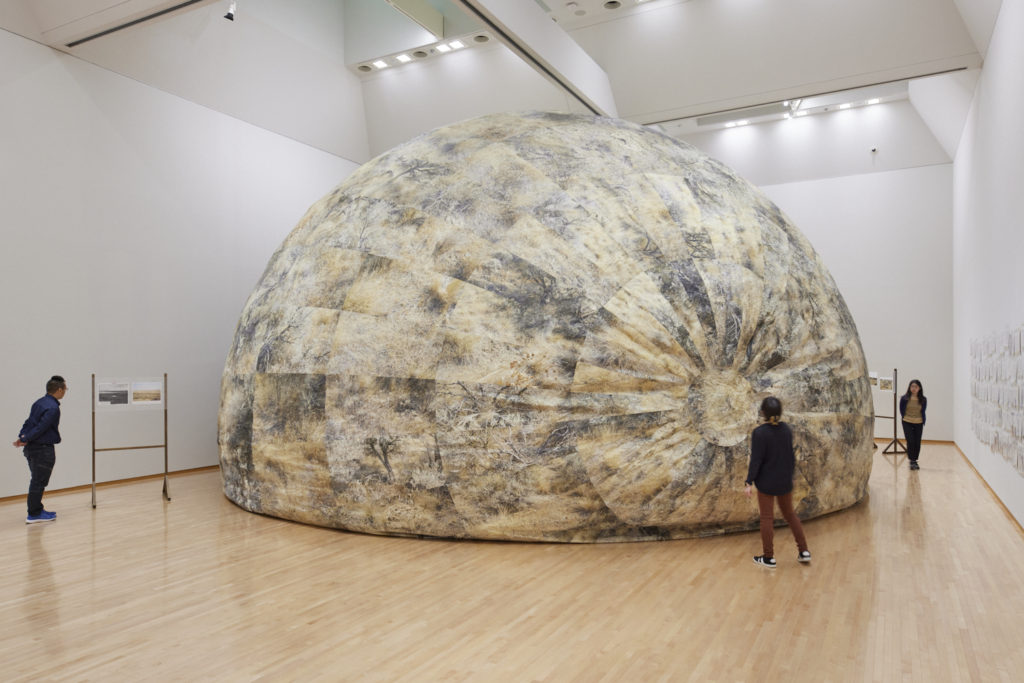

After taking the escalator upstairs with the bustle of the Dior exhibition to my side, I pass the organizers’ greeting inscribed on the wall and enter a room filled with a video installation. This is Lieko Shiga’s When the Wind Blows (2022–23), in which a person walks on a seawall with their eyes closed, while a narrator speaks. “We are now walking on a long road, built on the border between sea and land, and there is a strong wind passing through our body.” Following the numbers of the works listed on the exhibition handout, I enter the next room through a narrow corridor and come into view of Kota Takeuchi’s expandable installation Sigh of A Ground (2022). This area focuses on the balloon bombs from the Pacific War that Takeuchi has researched, with the large volume of these weapons being recreated here. Other related works are also on display, but some of the captions are set up in the back of the room, which makes the viewer wonder. As it happens, the title of the exhibition, “Waiting for the Wind,” and the names of the artists, Lieko Shiga and Kota Takeuchi, are displayed prominently on the wall in the next room. Come to think of it, I had come here through an untitled exhibition space, so perhaps the reverse route that immediately leads to this room is the correct one? I was worried for a moment.

Apparently there’s no fixed route to follow, and you do see movies where the title appears in the middle or at the end of the film. The Tokyo Contemporary Art Award (TCAA) winners’ exhibition always features two artists, but in the past, this has been accomplished in the form of two solo exhibitions on the same floor. This time, however, things are different. The two artists have agreed on a common title, and depending on the direction in which viewers turn, the winners’ works appear alternately, with Shiga coming first, followed by Takeuchi. Of course, the two artists’ works do not overlap, but neither are they unrelated, as both are based in the Tohoku region—one in Miyagi, the other in Fukushima—and have created art inspired by the tsunami and nuclear accident that were brought on by the Great East Japan Earthquake. More than a decade has passed since then, and with the recovery process considered complete to an extent in Japan, the disaster is being forgotten, shuffled out of sight by the worldwide pandemic becoming the primary cause of concern. However, the TCAA, held since 2018, and its system of selecting two award winners has, perhaps inadvertently, provided us with an opportunity to think once again about Tohoku and 3.11, as well as explore their relationship with Tokyo, the venue of the exhibition.

SHIGA Lieko, When the Wind Blows, 2022-2023, video installation, endless Photo: TAKAHASHI Kenji Photo courtesy of Tokyo Arts and Space

TAKEUCHI Kota, “Waiting for the Wind: Tokyo Contemporary Art Award 2021-2023 Exhibition” installation view, Museum of Contemporary Art Tokyo, 2023 Photo: TAKAHASHI Kenji Photo courtesy of Tokyo Arts and Space

As the English title of the exhibition, “Waiting for the Wind,” suggests, both artists take the wind as their motif. The matter of being invisible is also central. Shiga’s narration in When the Wind Blows looks back on the winds that have blown in Tohoku, from the easterly winds that once caused famine to the rush of post-earthquake “reconstruction” plans, and concludes by saying, “When I look at the waves…I think I can now see what I could not see before.” On the other hand, the balloon bombs developed by the Japanese military had no power source and literally blew to the U.S. with the wind, making it impossible to aim them. Hence, they were blind weapons that could fall anywhere. Takeuchi has tried to imagine, after the fact, what the balloons saw on their journeys. Yes, Japan and the U.S. are connected by the Pacific Ocean. At the venue, I suddenly recalled a story from the time after the Great East Japan Earthquake. In 2012, a technician working at a radar facility on an island in Alaska found a soccer ball washed ashore on a beach. The writing on it eventually made it possible to return the ball to its owner, a high school student in Iwate Prefecture.

In wartime, things otherwise thought unthinkable are given serious consideration. In the field of architecture, bamboo-reinforced concrete was used due to a shortage of steel, and the air defense plans of the time even included a proposal for surrounding cities with balloons that would serve as aerial barriers. The balloon bomb operation was carried out, with some 9,300 of these devices being released. In one particularly striking incident in 1945, balloons reached the Hanford Site in the state of Washington and blacked out a plant producing plutonium to be used in nuclear weapons. Later, the plutonium produced at Hanford was used in the atomic bomb that destroyed Nagasaki, and a mock A-bomb of the same type was dropped on the city of Taira in Fukushima Prefecture, where the balloons had been released. After the war, some of the remaining balloons were dumped in a coal mine in Fukushima, and the Daiichi nuclear power plant was built on the site of a former suicide attack training airfield in the Hamadori region. In the wake of the 2011 accident, local government leaders and academics visited the Hanford Site. They saw the site as a model for Fukushima’s future recovery, as it had come to host an advanced scientific research facility despite the land being contaminated by radioactive waste. In fact, Fukushima is in the process of attracting such companies and development is proceeding. This suggests that balloon bombs and Fukushima have a strange connection. Incidentally, radiation is also invisible. It can only be visualized by the numbers displayed on Geiger counters and other measuring instruments.

In any case, one can only marvel at the contents of the declassified documents from U.S. archives. In a similar undertaking, the artist Yusuke Kamata obtained, and used in an exhibition of his, drawings and other documents related to the U.S. Army’s construction of Japanese-style houses in the desert in cooperation with the architect Antonin Raymond—who had temporarily returned to America from Japan—for the purpose of developing incendiary bombs. Takeuchi used a variety of documents related to balloon bombs for this exhibition, and by imbuing them with his imagination, elevated the topic into a work of art. The Japanese military appears to have burned the materials related to this matter, and even in the 21st century, the destruction of important court documents is an ongoing process in this country, where official records are being disposed of at the behest of politicians. After all, Japan doesn’t even have a public museum summarizing the Pacific War. “National September 11 Memorial & Museum” (9/11 Memorial & Museum) in New York provides a painstakingly collected and meticulously displayed record of that disaster, while Japan’s Tsunami Memorial Museum is devoid of any such passion. The Great East Japan Earthquake and the Nuclear Disaster Memorial Museum in Minamisoma, despite dealing with an accident of world-historic proportions, is a rather bland affair that leaves the responsibility for the disaster ambiguous. The weak will to document in Japan is a fatal flaw. Therefore, when I served as the artistic director of Aichi Triennale 2013, I thought it would be important for art to take on the role of carrying memories along, so I established the theme of “Awakening — Where Are We Standing? — Earth, Memory and Resurrection”*1 for the festival.

Shiga’s videos and installations have the daydream-like feel of her previous photographs, but this time they are extremely eloquent. In the video, a woman with a microphone speaks directly toward the screen, and as one approaches the huge photographic mural Where that Night Leads, one notices how countless small photographs, words, quoted text, and an oddly powerful map with a thick red line marked “The Human Highway” are superimposed on it. The work condenses what Shiga must have experienced and thought about in the aftermath of the disaster, and despite the event’s proximity to the present, feels like it revisits the myths that have been told from the time of Japan’s modernization. In the exhibition, Shiga touches on the plan to build a casino resort in coastal Miyagi Prefecture, an idea that was scrapped almost as suddenly as it was proposed. I remember Shiga angrily referring to this when I asked her to participate in Aichi Triennale 2013, but the matter did not immediately turn into a work of art. Other references include the massive seawalls built in the name of reconstruction and the so-called Fukushima Innovation Coast Framework, examples of how the powers of state and capital were allowed to rage in the aftermath of the natural disaster. These are not problems exclusive to Tohoku. In fact, the capillary-like map drawn with red lines covers the area from Tokyo to Tohoku, implying that these are connected, or rather, that the “veins” have been feeding the “heart” that is Tokyo.

TAKEUCHI Kota, “Waiting for the Wind: Tokyo Contemporary Art Award 2021-2023 Exhibition” installation view, Museum of Contemporary Art Tokyo, 2023 Photo: TAKAHASHI Kenji Photo courtesy of Tokyo Arts and Space

SHIGA Lieko, Where that Night Leads, 2022, installation Photo: TAKAHASHI Kenji Photo courtesy of Tokyo Arts and Space

Finally, marking is yet another motif shared by the two artists. Takeuchi, who also styles himself an agent of the worker famous for pointing a finger at the Fukushima Daiichi live camera, in Site Marking (Prosser) and Shooting (Cold Creek) (2022) draws a cross with his foot where a balloon bomb once existed, and imitates with his finger the one-time act of shooting a gun at such a balloon. In the absence of any monuments, his acts function as reminders of past events that occurred in these places. Similarly, Shiga’s Where that Night Leads is marked with a large red cross on the wall and a blue cross on the floor. The man who appears in one of the photos marked a piece of heavy machinery that had been swept away by the tsunami with a cross to indicate that it was his possession, and brought the equipment onto his property deep in the mountains of Fukushima before it could be removed as “debris.” Perhaps this place exercises strong resistance against the fading memory of the Great East Japan Earthquake. Marking is a process of self-identification, of indicating where one stands in the face of a situation that has disappeared from view.

*1 https://aichitriennale2010-2019.jp/2013/about/about_01.html

Translated by Ilmari Saarinen

INFORMATION

Waiting for the Wind

Tokyo Contemporary Art Award 2021-2023 Exhibition

Period: March 18 – June 18, 2023

Venue: Museum of Contemporary Art Tokyo

Organizers: Tokyo Metropolitan Government and Tokyo Arts and Space / Museum of Contemporary Art Tokyo of the Tokyo Metropolitan Foundation for History and Culture

Open Hours: 10:00-18:00 *Open until 20:00 on Sat. and Sun. from May 13(Sat.) to 28(Sun.).

Admission: Free