Architectural historian and critic, was born in 1967 in Paris. Professor at Tohoku University. Commissioner for Japan pavilion at the Venice Biennale of architecture 2008. Artistic director of Aichi Triennale 2013 Publications include “Contemporary Japanese architects : Profiles in design”, “Architecture and Music” etc.

photo by Saito Akihide

In this work, the audience watches a 90-minute film comprising dream-like imagery. Or perhaps one could say, the audience is invited to experience entering a dream. The venue for the work is the Tokyo Metropolitan Theater, which of course is a place where performances are held everyday, enabling people to enjoy the worlds of various stories and narratives that are separated from the context of everyday life. “FEVER ROOM” however, presents us with an experience that transcends the standard framework of cinema. Apichatpong states “I see this work as a film” and considers that “it is possible to see other people’s dreams through watching the film” (excerpted from an interview by Atsushi Sasaki featured in the film’s pamphlet). While the work comprises light and footage projected onto screens, it indeed differs from the format of a standard film. In the same way as he attempts to do so in museum exhibition rooms, Apichatpong prepares an installation employing film within the theater.

photo by Saito Akihide

My elaborating any further may result in revealing important plot points of this work. That being said, is there a danger of spoilers in the first place? Needless to say, the film is not a mystery that entails finding a certain culprit. On the contrary, as the artist himself mentions, “There is very little of what you could call a story. What you simply see are youths, someone sleeping on the bed, scenes from inside a cave and so on. These elements are not connected, and there is no story there” (Ibid). In other words, while motifs such as sleeping people, as well as the same actors who also appear in Apichatpong’s other works can be observed, it is not a type of work that invites the audience to solve something or reach a conclusion based on what is shown. Furthermore, rather than allowing the audience to enter 30 minutes before the start, they are left to wait in the foyer until the last minute, after which they are guided to a given position via a narrow passage. This spatial scheme is what serves as an important key, however it does not constitute the entire work. No matter how much I try to articulate in words, the actual experience of the work is far richer.

photo by Saito Akihide

From here on, allow me to discuss the way in which the space of the theater was used. We are guided onto the stage, and sit facing where the audience would usually be seated. All the while, the curtain remains closed. I have experienced theater performances in the past that invite the audience to sit on the stage, yet this work seemed to be in a different dimension to such productions. First of all, a screen is lowered from above, onto which a scene of a person sleeping in a hospital in projected. Screens also appear on the left and right of the stage in addition to the front, with each split into two levels of top and bottom. Surrounded by footage and sound, the film gradually shifts to a scene of wandering inside a cave. However, the large curtain that separates the audience area and the stage remains closed, leaving us to imagine what lies beyond it. As I had participated without much background knowledge of the work, I assumed that the actors were perhaps on stand-by. When the curtain was finally raised during the latter half of the work, I was taken by surprise. What lay before my eyes, were row after row of empty audience seats.

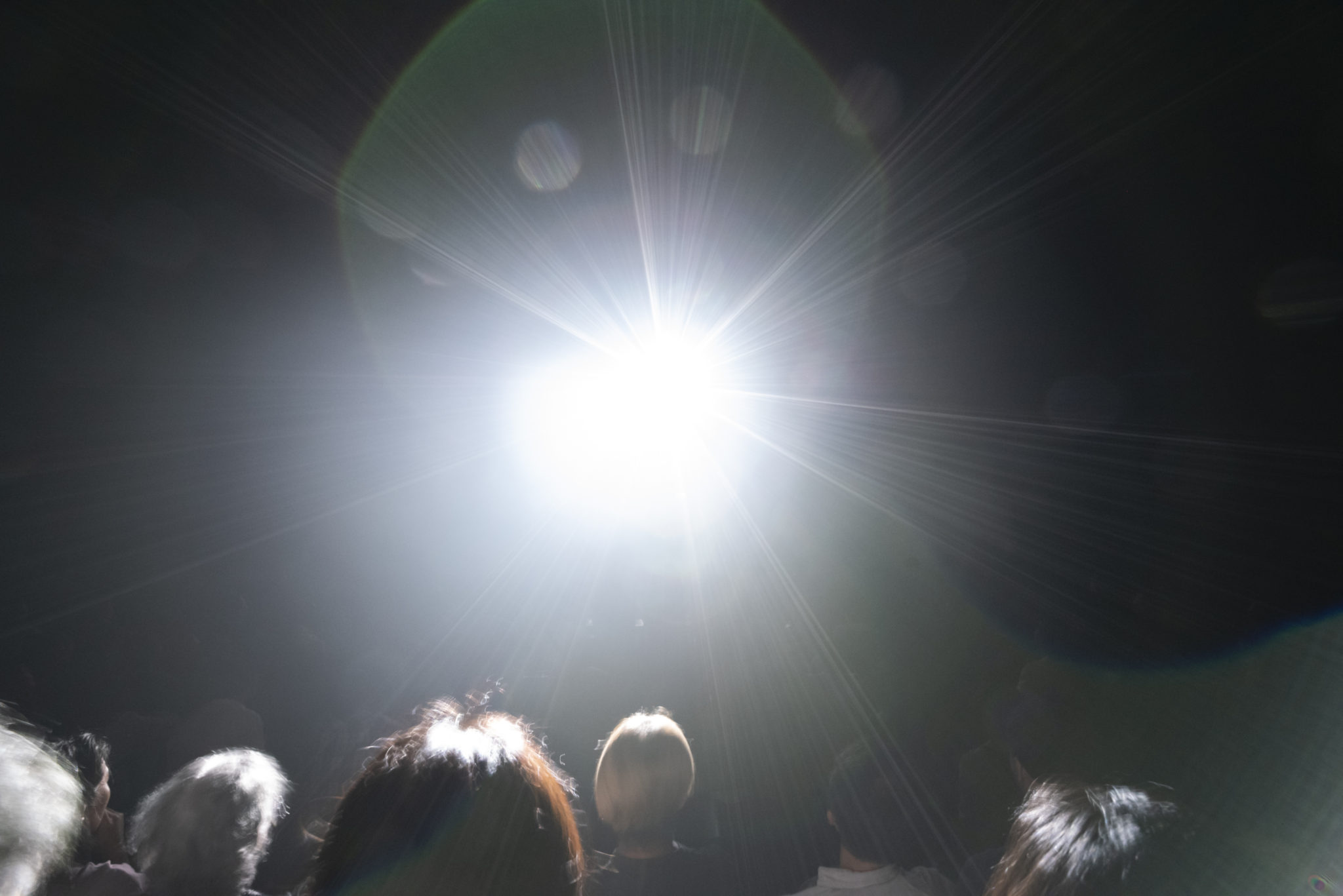

photo by Saito Akihide

Although the work is presented in a theater instead of a cinema, there are no live actors that appear and perform in front of the audience. Streetlights stand amidst sounds of torrential rain and thundering lightening. Eventually clouds of smoke rise, and we find ourselves immersed in the ever-changing and overwhelming light that is emitted from the projector. Usually in a cinema, what the audience sees is the reflected light of the image projected onto the screen. In “FEVER ROOM” however, Apichatpong completely reverses this visual structure that has permeated the long history of film (including its prehistory such as magic lanterns). We are not looking at a concrete image through reflected light. We are in fact both looking at and enveloped in the light that directly shines towards us. Indeed, we ourselves are on the other side of the screen. From the empty audience seats to the stage full of people, and from the series of scenes observed just before, it also felt as if one was in a dream. While the light does not reproduce a specific scene, the combination of smoke and the geometry of sharp laser-like light instill in us the sensation of floating, as if we were drifting amongst the clouds. That being said, associations may differ completely according to each person.

photo by Saito Akihide

It is a work in which a group of individuals are respectively immersed in different dreams at the same time. In the context of our era, it is comparable to current circumstances whereby Hollywood films produced on massive budgets work to strengthen the reception of the same story through offering 3D and 4D visual experiences that transcend two-dimensional realism. What “FEVER ROOM” does is undermine the spatial structure of the building type=theater which is the predecessor of the cinema (I suspect it is not possible to present this work in a cinema as the space behind the screen is too narrow), essentially giving rise to a miraculous film experience. If I were to borrow the artist’s own words, “it is a live cinema that requires a special space.” Having the audience sit still throughout the work could indeed be considered a traditional format. According to his interview, Apichatpong seems to be more interested in virtual reality that continues to evolve with the times, than with 3D. Should he attempt to create a work using VR technology in the future, it may manifest in the form of a post-theatrical film space that enables the audience is to move around freely.

Translated by Kei Benger

INFORMATION

"Asia in Resonance 2019"

Apichatpong Weerasethakul "FEVER ROOM"

Date: 2019.6.30 - 7.3

Venue: Tokyo Metropolitan Theatre, Play House

Director & Editor: Apichatpong Weerasethakul

Cast: Jenjira Pongpas Widner, Banlop Lomnoi, Teenagers of Nabua