Dance journalist / critic. Has been contributing articles to newspapers and magazines such as DANCEARTand Theatre Arts. Member of AICT, and co-director of the Maiboku no Kai. Co-authored publications include ”Future of Performing Arts from Quebec” (Sangen-sha), ”54 Chapters to Know About Quebec” ( Akashi-Shoten), and ”Modern Dance in the Theatre of War, Takaya Eguchi and Misako Miya’s Modern Dance Group Touring in the Battlefront (canta).

Photo by yurika kono

This new performance by contact Gonzo is a work that zeroes in on the skin, both as a sensory organ that picks up minute information from the outside and as an interface that itself transmits information[1].

The titular binta (“slap in the face”) evokes the act of striking someone, whereas the “contact” in the group’s name can mean touching someone physically. I attended the performance at Hillside Plaza in fashionable Daikanyama eager to see how the group had decided to approach the skin as a bodily organ, what kind of worldview they would present, and how this piece would differ from contact Gonzo’s past works.

Photo by yurika kono

Photo by yurika kono

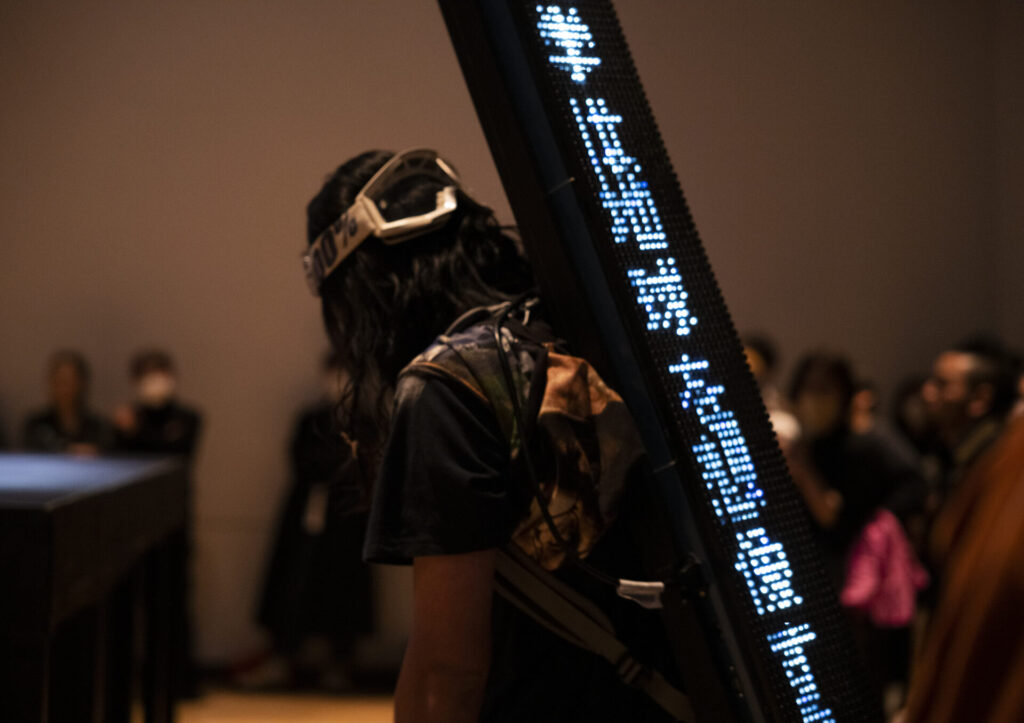

Earplugs were provided at the reception on the first basement floor. Not being fond of loud noise, I chose to wear mine throughout the performance. On display near the reception desk were items such as enlarged photos and calendars depicting skin fragments, and audience members were handed copies of a newspaper in which a novel written for the performance was laid out like a feature article in an English-language newspaper[1]. The performance venue was downstairs on the second basement floor and centered on a stage that looked like a ring for boxing or some other combat sport. Beneath the ring were installed a total of eight giant bass speakers that faced the audience in pairs. The venue was filled to its 100-person capacity (though there were no seats; this was standing-room only) and brimming with anticipation, and people carrying electronic billboards were milling about in the crowd.

Photo by yurika kono

Photo by yurika kono

A fistfight between four performers broke out on stage. All participants had detectors attached to their bodies, and each time one of them punched the other, a heavy bass sound echoed through the space. The performance seemed like one big brawl, with the wild scuffle going on and on and on.

Once this onstage battle that made up the first half of the piece ended, everyone in the audience held hands to form a circle, communicating our movements and feeling “real” contact, bringing about a sense of shared experience. The performance then resumed with another brawl beneath the stage, where the foursome exhibited intense movements and kept punching each other. Some onlookers pulled back to avoid getting hit while others moved in for a better view of the action, adding to the dynamic scene. When the performers returned to the ring, the show took a different turn by pivoting to a theatrical scene. Some of the performers grilled meat on a hotplate and placed it on their skin (to “treat a wound”), and we also saw a body scrub being performed.

Whenever one of the performers landed a punch, the touch switch attached to the recipient reacted to the blow, multiplying the vibrations and producing a heavy bass blast from the giant subwoofers. These low-pitched tremors disturbed the air around us and drove vibrations through our bodies, shaking us to the core. Long-wavelength, heavy bass sounds travel through water and human tissue just as well as through air, shaking the entire body. These sound frequencies thus transmitted the violent fisticuffs on stage to us onlookers’ bodies, making the entire audience shudder. This was a performance that stimulated the senses of sight, sound, and touch so intensely that it was impossible to remain a passive bystander.

Photo by yurika kono

The roots of contact Gonzo’s style of performance are in contact improvisation, a method of improvised dancing developed by Steve Paxton and his colleagues in 1972, more than half a century ago. When I saw them perform previously, I was impressed by their hard, aggressive style—buff, lively guys bumping into each other and rolling around, pushing themselves to the brink of injury. At the same time, I felt that they managed to express the essence of contact improvisation in a rich, vivid way. This time, however, the intensity of the contact was on another level, functioning within the performers not as a tool but as a trigger (for expression). As they push to explore new horizons and develop their very own form of expression, these activities also appear like a new development within the structure (or operating system) of contact improvisation, or an effort to broaden its base.

As we approach the mid-2020s, contact Gonzo’s gaze has turned to the audience in front of them, seeking a more intense way to engage onlookers that doesn’t leave them on the sidelines. By turning their audience from bystanders to participants, they are inviting each and every onlooker to become a member of the community that emerges in the performance space, creating a sense of empathy that coexists and resonates in the same space.

Quietly beating each other’s bodies, wrapped in the bag that is skin, as if they were sandbags, is at once a violent and self-deprecating act. Is it a way to ease anxiety in the face of an uncertain future? A rite of passage of sorts on the way to becoming something else? Or is it an outburst of anger at something inexplicable or unreasonable? With less direct communication between people and ever more flame wars in the virtual world, gaining mutual trust and empathy on a skin-to-skin level is becoming increasingly difficult. Maybe the members of contact Gonzo are punching each other in an effort to feel the real presence of another human. Paradoxically, hitting and being hit, and the resulting sharing of pain, may just solidify the restoration of trust and create a sense of solidarity—a sense of having eaten out of the same pot, if you will.

In his book “Liquid Modernity,” the sociologist Zygmunt Bauman describes contemporary society as a “cloakroom community” (or “carnival community”). When going to see a play, one leaves one’s coat and baggage at the cloakroom before entering the theater, where one laughs or weeps together with the rest of the audience, forming a community of sorts. But when the show is over, everyone gets their belongings from the cloakroom and heads for the exits; once the audience leaves the building, everyone goes their separate ways and the community disappears. In Bauman’s view, this is an apt parable for today’s society.

The communality and sense of bodily resonance that existed between the performers and the entire audience may be gone, but the memory of that skin sensation remains. As virtual reality technology becomes ever more advanced, the way it suppresses and burdens the body is becoming a major issue. A performance with an excess of contact, in which hard hits aren’t spared, may also be meant as a warning against this trend.

Photo by yurika kono

I am reminded of Steve Paxton, who in an interview he gave when visiting Japan said, “Putting everything that underpins contact improvisation into practice, including equality and the idea of non-competitive relationships, has the potential to change society. But despite the fact that tens of thousands of people around the world have practiced contact improvisation, the world hasn’t changed much for the better, and we still have wars…” (May 2009)

Contact improvisation, which seeks to create new forms of interpersonal communication, has evolved from an artistic experiment into a social movement. With that in mind, contact Gonzo’s artistic performances appear to express an unprecedented thirst for communication. Finding the key to a new kind of communality in a new world won’t be easy, but that’s exactly why it’s worth looking for. And I do hope it will be found.

[1] The group has been exploring the theme of skin from a variety of perspectives as part of its activities under the Art Incubation Program’s Fiscal 2023 Artist Fellow framework, organized by Civic Creative Base Tokyo (CCBT), creating works by way of practices including research and workshops.

[2] The sci-fi-esque story revolves around how contact Gonzo and their descendants develop a new form of communication based on skin-to-skin contact. This performance is described as the moment they discovered the technique—a moment attended by someone from the future. Skin is emphasized to a grotesque degree.

Translated by Ilmari Saarinen

INFORMATION

Performance stage by contact Gonzo “my binta, your binta // lol ~ roars from the skinland ~”

Date: March 1 - 3, 2024

Venue: HILLSIDE PLAZA (29-10, Sarugaku-cho, Shibuya ward, Tokyo)

Production: contact Gonzo

Organizer: Civic Creative Base Tokyo [CCBT]

Performers, Concept building: contact Gonzo (Tsukahara Yuya, Mikajiri Keigo, Matsumi Takuya, NAZE)

Concept building support: Tsuda Kazutoshi

Stage director: Kawachi Takashi

Acoustic design: Nishikawa Bunsho

Acoustic operating: Mizoguchi Hiromi (Nancy)

Device design: Inafuku Takanobu

Lighting design: contact Gonzo

Technical support: Ito Takayuki (CCBT)

Visual design, Costume: Aiko Koike

Drawing archive: NAZE

Production: Hayashi Keiichi, Iwanaka Kanako, Shimada Mei (CCBT)

Cooperation: happy freak