Specializes in studying the relationship between technology and society through the lens of media art, a comparatively new form of artistic expression. She has applied her research to planning and producing exhibitions, and conducting workshops for understanding and experiencing media technology as part of exhibitions and education, as well as in medical settings. She is also involved in developing technology-based support mechanisms for appreciating art. A graduate of the International Academy of Media Arts and Sciences (IAMAS),she has worked as a researcher at IAMAS, a director of the Digital Pocket nonprofit organization, an associate researcher at the Agency for Cultural Affairs, and as a program officer at the Japan Arts Council’ . She is currently an associate professor in the Nippon Institute of Technology’s Faculty of Advanced Engineering Department of Information Technology and Media Design.

Photo: Yurika Takano

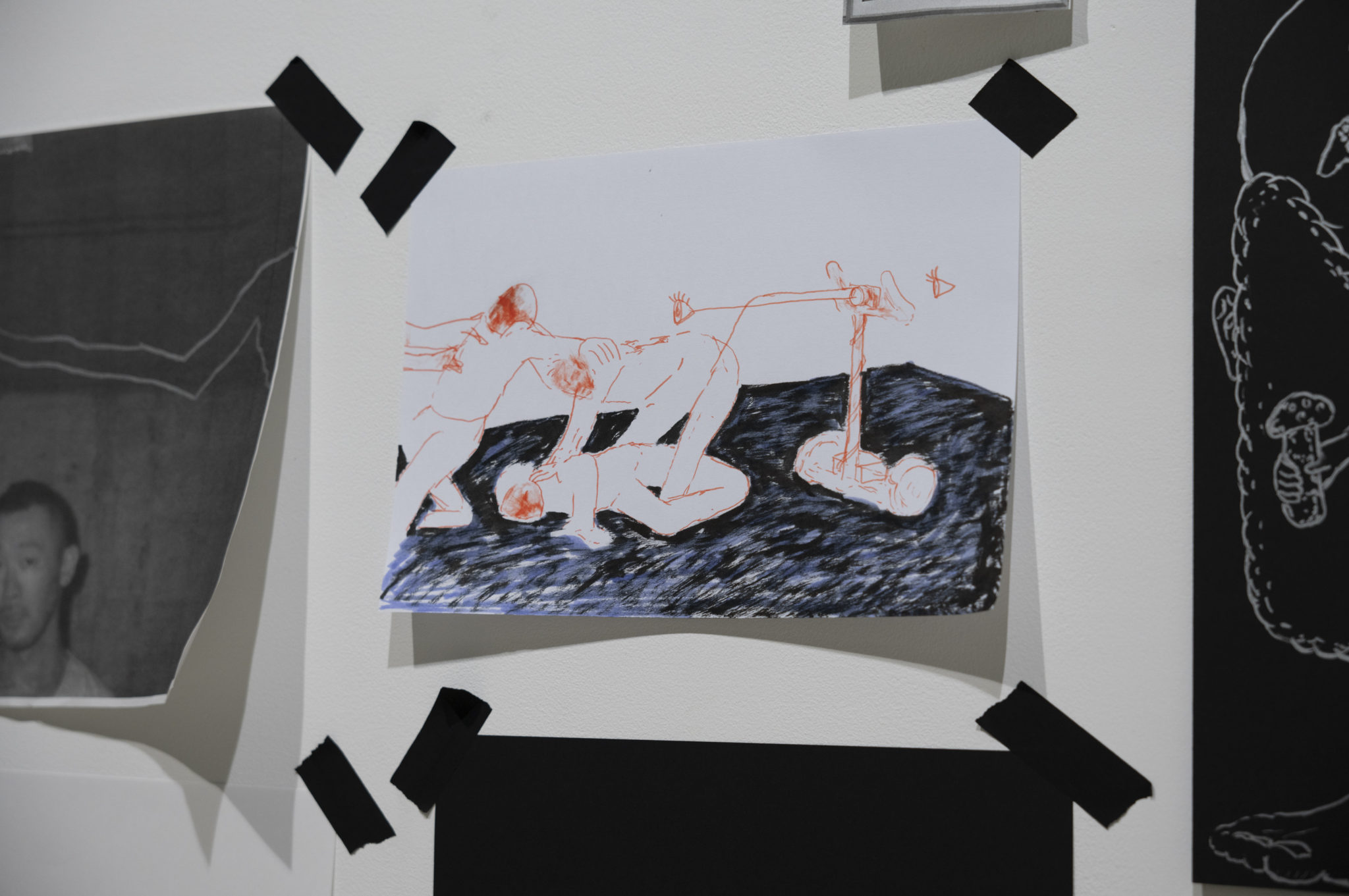

This work by contact Gonzo and yang02 was the continuation of an “untitled session” presented at Tokyo Arts and Space Hongo in 2019. In the performance, members of contact Gonzo are seemingly attacking each other as if they were fighting, all while an automatic guided vehicle (AGV) and a Segway modified to move on its own seek to “observe” and “explain” the scene. The performance was preceded by a work-in-progress version presented in Osaka in March and documented in a published report.*1

*1 https://theatreforall.net/feature/feature-8568/

On the official website, two main points are raised pertaining to the work. One is cooperation with artificial intelligence (AI), and the other that the performance is being conducted as part of a festival called “TRANSLATION for ALL.”*2

*2 https://theatreforall.net/join/jactynogg-zontaanaco/

Let’s begin by addressing the first point, collaboration with AI.

The work makes use of a technology called image captioning, which automatically generates captions (or descriptive text) for images. The AI analyzes an image, detecting shapes and features in it, and interprets its content by recognizing objects in the image and their relationships. It then generates a caption using natural language processing methods such as deconstructing sentences to understand grammar and structure, understanding meaning from context, extracting specific information, and determining emotions and opinions contained in a sentence.

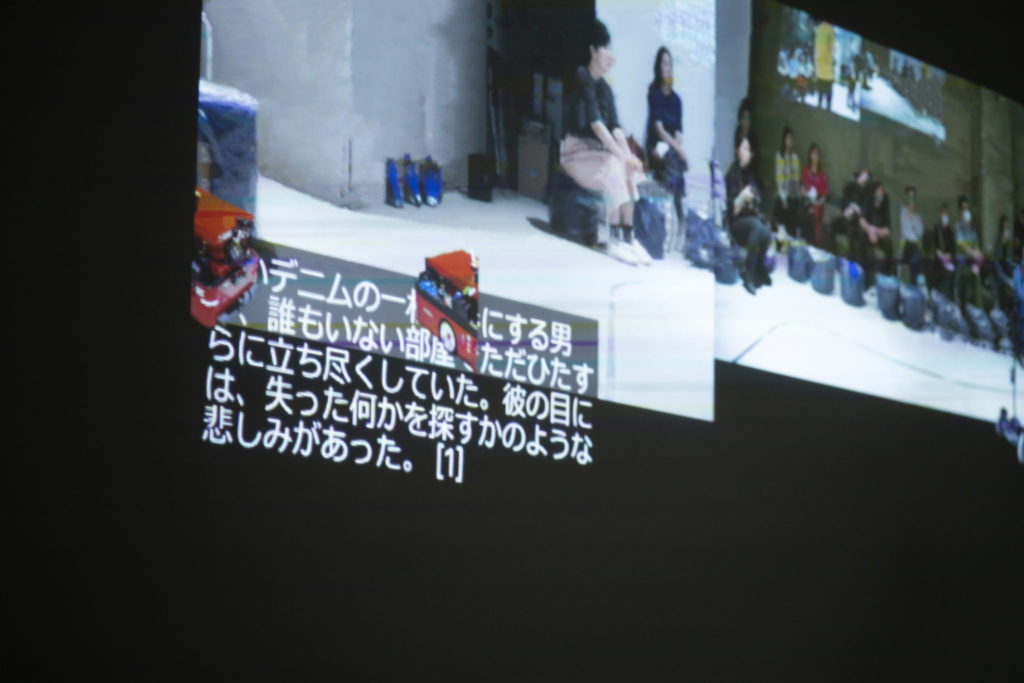

Silver lines on the floor of the venue served as tracks for the AGV, which can carry a load of up to 100 kilograms and sometimes moved with a performer on board, while the Segway had been modified to move autonomously without a human driver. Cameras mounted on each of the devices took still images every ten seconds or so, and AI-generated captions for those images were projected onto the venue’s walls. The AGV’s captions were read out in a male computer voice, the Segway’s in a female. Since audience members could be exposed to the machines’ cameras, contact Gonzo provided masks to those who wished to hide their faces.

Photo: Yurika Takano

contact Gonzo’s performances resemble a martial art, with the participants’ bodies colliding repeatedly with each other, and it isn’t clear whether any rules govern their movement. The heavy sound of body slams and the performers’ disordered breathing make one feel uneasy. Explaining the scene in words would seem very difficult. For the purposes of this work, the AI was described as playing the role of a translator that converts the performance into language. How did that turn out?

As in the image below, the AI-generated captions described something different from that happening in front of my eyes. But was it really “different”?

The performers made adjustments such as changing costumes and picking up instruments, as if fighting to see how the AI would interpret them while their performance. I guess they were trying to see if they could get it to produce an appropriate caption. But looking at the captions actually generated, one could vaguely make out the content of, and trends in, the data the AI had been trained on, and I felt like I was watching the show while chatting with a non-human intelligence—an interpretation more interesting than evaluating the AI’s abilities for translation or explanation. The AI appeared to pick up a certain sadness in the performers’ eyes, one I didn’t see.

Photo: Yurika Takano

Let’s move on to the second point, “TRANSLATION for ALL.”

As stated on the project’s website, “There are all sorts of barriers on the road to delivering physical expression to audiences. The various works [presented] are taking up the challenge of overcoming [those barriers] through diverse techniques and opening up accessibility to ALL, meaning all kinds of people.”*3

*3 TRANSLATION for ALL: https://theatreforall.net/translation-for-all/

The organizers added live commentary by a human after the work-in-progress performance, and at the dress rehearsal of this showing they consulted a monitoring group composed of visually impaired individuals. The commentary was provided by the dancer Akiyoshi Nita, who whispered into a microphone, as if bringing an explanation intended only for someone right next to or in front of him to the entire audience. Conveying the progress of the performance and the participants’ movements, Nita’s commentary accurately described the way these bodies were moving—such as how arms were bent—and their intricate interplay, all while infusing his words with the atmosphere of the scene and the rhythm of the performers. His rap-like delivery made for pleasant listening.

Photo: Yurika Takano

The AI “chatter” and Nita’s commentary were enjoyable as elements of the performance, but how did they further the goal of “opening up accessibility to all”? In the project handout, this was addressed as follows: “In an attempt to promote accessibility in the appreciation of artworks, we will attempt to ‘translate’ physical expression by incorporating, as elements of the artwork, verbal explanations of the performance by an AI and a human, as well as textual support through UD TALK [a communication support app developed in Japan] and subtitles.”

By including elements such as commentary, linguistic explanations, and UD TALK compatibility, the organizers had undoubtedly gone to great lengths to help the audience enjoy the work. However, I felt that including these “as elements of the artwork,” and making the work/performance accessible in itself, are matters that differ in kind.

Artistic expression focuses on issues related to the method and intent of an artwork, while accessibility emphasizes making that artwork approachable to anyone. Precisely because this performance was experimental, I felt that it could have involved people with a stake in accessibility from the outset, thereby enabling the organizers to separate and coordinate these aspects—and open up even greater artistic possibilities.

Let me end on a different note. During the intermission, the owners of Leggy_ (plant sales) and Ken-chan Curry, who had stalls at the venue, talked about how they are attracted to plants that have grown into unwanted shapes and collect them by going from one gardening store to the other. Similarly to these overgrown succulents, “jactynogg zontaanaco” appeared to reveal the appeal of AI that materializes in situations beyond the optimal. I look forward to seeing new attempts in this vein in the future.

Translated by Ilmari Saarinen

INFORMATION

contact Gonzo X yang02 “jactynogg zontaanaco ジャkuティー乃愚・存taアkoコ”

Dates: May 19 – May 21, 2023

Venue: ANOMALY

Direction / Composition: contact Gonzo, yang02

Cast: contact Gonzo (Yuya Tsukahara, Keigo Mikajiri, Takuya Matsumi, NAZE)

Technical Design: yang02, Takanobu Inafuku (HAUS)

Stage Manager: Takashi Kawachi

Commentary: Akiyoshi Nita

Organizer: precog Inc.

Supported by: Arts Council Tokyo, Japan Arts Council

Cooperation: ANOMALY, Chishima Foundation for Creative Osaka