Born in Tokyo. Graduated Keio University Faculty of Literature, Department of Philosophy, aesthetics and art history major. Since 1990s, She has been at the forefront of the Japanese art scene as a writer / art journalist / art producer. 2003 spring, launched an art bar TRAUMARIS in Roppongi, was moved to Ebisu NADiff building, as an alternative space TRAUMARIS where art exhibitions, live performances, food and drink can be enjoyed. After closed the space, is currently involved in various art activities beyond the boundaries of the genre as an art producer. A jury for Yokohama Dance Collection’s competition from 2011 to 2016. A producer of Dance and Nursery!! Project since 2016. Established RealJapan project as a co-director. http://www.traumaris.jp Photo by Mari Katayama

Photo by Rikimaru Hotta Courtesy of New National Theatre

Claude Debussy’s only opera, “Pelléas et Mélisande,” is based almost directly on the script of a play by the Belgian Symbolist poet and playwright Maurice Maeterlinck, best known for his fairy tale play “The Blue Bird.” The New National Theatre’s production of the opera was directed by Briton Katie Mitchell, whose bold interpretation with its distinctive radical realism and gender perspective made waves when it premiered at the Aix-en-Provence Festival in 2016.

Photo by Rikimaru Hotta Courtesy of New National Theatre

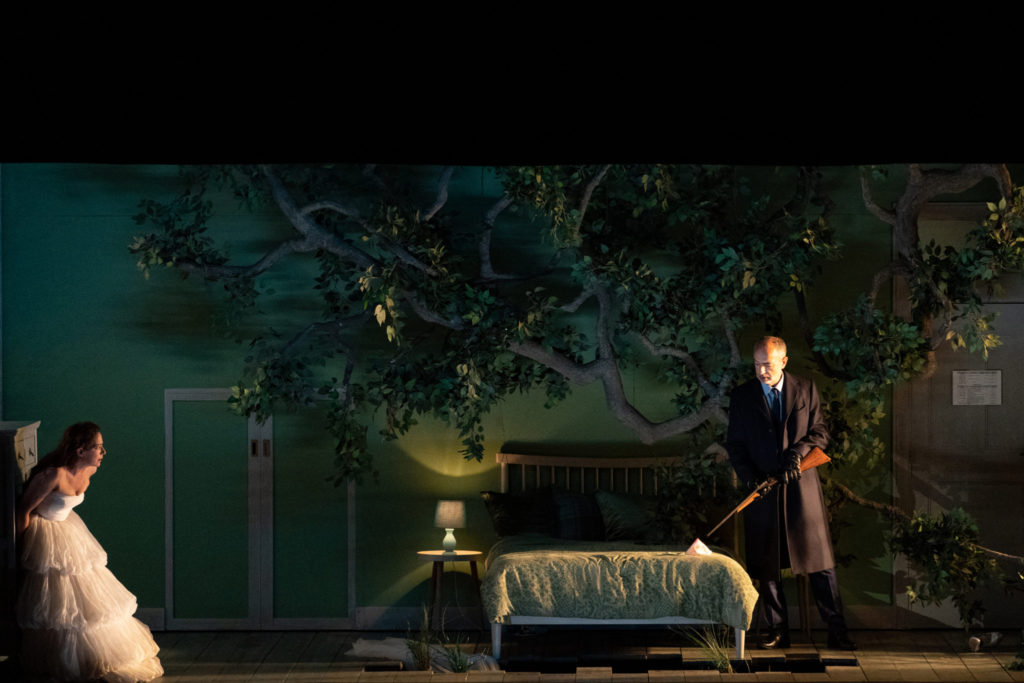

In silence, a woman in a wedding dress enters a hotel bedroom. Her nose suddenly starts to bleed. She wipes away the blood with a white handkerchief and, seemingly exhausted, falls asleep. Music is heard for the first time, and the story unfolds in the woman’s dreamscape. The “it was all a dream” dramatic device has received mixed reviews, but I took it as a choice that leaves space for interpretation and allows for a deep reading from multiple perspectives. In the next scene, the hotel walls and bed are half-transformed into a dense forest grove. The setting is the fictional country of Allemonde. Golaud, a somewhat aged prince, is out hunting when he encounters a weeping maiden, Mélisande, by a spring and takes her home. The two marry and Golaud brings Mélisande back to his father’s castle, but she and Golaud’s young half-brother Pelleas develop a mutual attraction. Upon discovering their relationship, Golaud becomes jealous and even forces his young son to peek into Mélisande’s bedroom. When Golaud finally catches the couple engaged in adultery by the fountain, he beats Mélisande and kills Pelléas. Mélisande eventually dies after giving birth to a baby girl.

Photo by Rikimaru Hotta Courtesy of New National Theatre

The original story is a fable set in a medieval-like period, but this production reimagines it in the form of a modern drama. The abrupt actions of a desperate woman wandering alone in the depths of the forest, giving in to the advances to a strange man—no matter how princely—and getting married without notifying her family are enigmatic to be sure. Still, the story may not be as farfetched as it appears, even when transported to modern society. Lonely and traumatized young women disappear into the forests of the internet and are abducted in the throng of our cities on a daily basis.

The distortions of time and space and the complexities of the human psyche are brought to the fore with symbolistic music, which subtly expresses the sounds of wind and water to suggest a disturbing atmosphere, and meticulously crafted and intricate scenography. The stage is divided into box-like sections reminiscent of a dollhouse, which open and close as if manipulated by a child playing with dolls. Scenes such as the hotel room at the beginning, the royal dining room, the married couple’s bedroom, a drained pool in an abandoned structure, and a spiral staircase leading to a basement are all imbued with finely honed beauty in their textures and details, and are brilliantly and elegantly shaded.

Photo by Rikimaru Hotta Courtesy of New National Theatre

The mirage-like, spacetime-bending staging of the tale around a fateful woman’s memories is reminiscent of Alain Resnais’ film “Last Year at Marienbad” and Luis Buñuel’s surrealist works. For example, from the scene in which Mélisande marries into the royal family, there are always two Mélisande on stage. This could be read as the character watching over another version of herself in her dreams, and simultaneously as an expression of the self-consciousness of a woman torn in two in a male-centered society.

Throughout the story, Mélisande appears to be a woman at the mercy of men’s sexual desires and repression, someone who has resigned her agency within patriarchal society. (This can be said with regard to her husband, brother-in-law, and father-in-law, and imagined to apply equally to the events before her escape into the forest.) In the climactic scene, however, she finally affirms her desires and embraces Pelleas. The porno-esque direction in this scene depicts the explosion of Mélisande’s ego with somewhat malicious humor. The life of a woman who is beaten by her husband, sees her lover killed, and ends up dying herself because she suddenly and fully seizes the agency she has been suppressing is simply too tragic. But in this production, that’s all a life in a dream. When awake, Mélisande is an independent woman who can act according to her own desires and free will, despite the nosebleed caused by the stress of her wedding. If this is the case, the final scene is more of a nightmare than a descent into a dream. It appears to depict her waking up from her nightmare, horrified to realize that in this world, by being born in the wrong place at the wrong time, she may have faced such a horrifying situation. Taking that view, this unfunny melodrama—in the vein of the Japanese comedy group Drifters’ “What If?” skits—comes alive as a frightening fable that remains relevant today.

Discussing the production, Katie Mitchell says she set out to portray “the prison-like world in which women are held captive” through a feminist lens. Debussy’s fantastical and unsettling music and the opera’s enigmatic romantic thriller of a plot are turned into a stylish highlighting of universal themes punctured by the contemporary feminist gaze, resulting in drama of the highest order.

Photo by Rikimaru Hotta Courtesy of New National Theatre

Looking back on the history of art and culture, one notices how many of the masterpieces based on the social norms of a certain time assume a male-centric perspective. When we view them with eyes from which the membrane of convention has been stripped by twenty-first century practical feminism, we sometimes feel uncomfortable, physically sickened, or ridiculous. It’s important for artists and creatives not to dismiss these emotions by thinking they can be rationalized and made compatible with social conventions, especially at a time when those very conventions are in need of change. The scalpel cuts of a radical director propel this work to reveal a woman’s struggle to achieve mental and physical independence. It reminded me of the vivid ending of Àlex Ollé’s 2019 version of “Turandot,” which was also performed with Kazushi Ono as conductor. Reaching beyond the convenient “dreamfall” ending, the story’s allegory of a woman shivering after waking from a nightmare remains ripe for discussion and reform.

Translated by Ilmari Saarinen

INFORMATION

Pelléas et Mélisande

Date: 2022.7.2 - 7.17

Venue: New National Theatre

Composer: Claude Achille Debussy

Conductor: Kazushi Ono

Production: Katie Mitchell