Theater director. Artistic director for Theatre Company ARICA since 2001. Directed the Japan premiere of György Ligeti’s opera “Le Grand Macabre” at the New National Theatre in 2009. Is also a part-time lecturer at Tama Art University.

©Rikimaru Hotta

Having had my belongings confiscated at the entrance, I stepped bare-handed into the darkness of an abandoned-looking warehouse, where a strange machine was emitting a sound. Half-naked men used ropes to descend from the ceiling high above us and, accompanied by the thunder of a rock band, got on a large cart, doused each other with water, scattered white powder around themselves, bit into cow entrails and threw them around, all while moving up, down and from one side to the other. The onlookers, having given no chairs to sit on, were left staring at the pandemonium, unable to escape even if they had wanted to. If was one of them, witnessing La Fura dels Baus’s performance of “Suz/O/Suz” in Yokohama in 1989. Àlex Ollé, the director of “Turandot”, was there too – as one of the half-naked men. Although seemingly a product of a very specific moment, this supremely festive performance was not just about chaos. Its theme of “violence and fraternity” was put together cleverly and expressed in a manner that had a physical impact on the onlookers, who were enticed to move together with the performers.

But what about Ollé’s take on “Turandot”? While the somewhat dirty masses of commoners, who also function as a choir, hark back to 30 years ago, the production itself is extremely refined; the “barbaric” touch is gone. Still, I sensed a strong desire to reinterpret the traditional “Turandot” – to once again make “violence and fraternity” its motif.

©Rikimaru Hotta

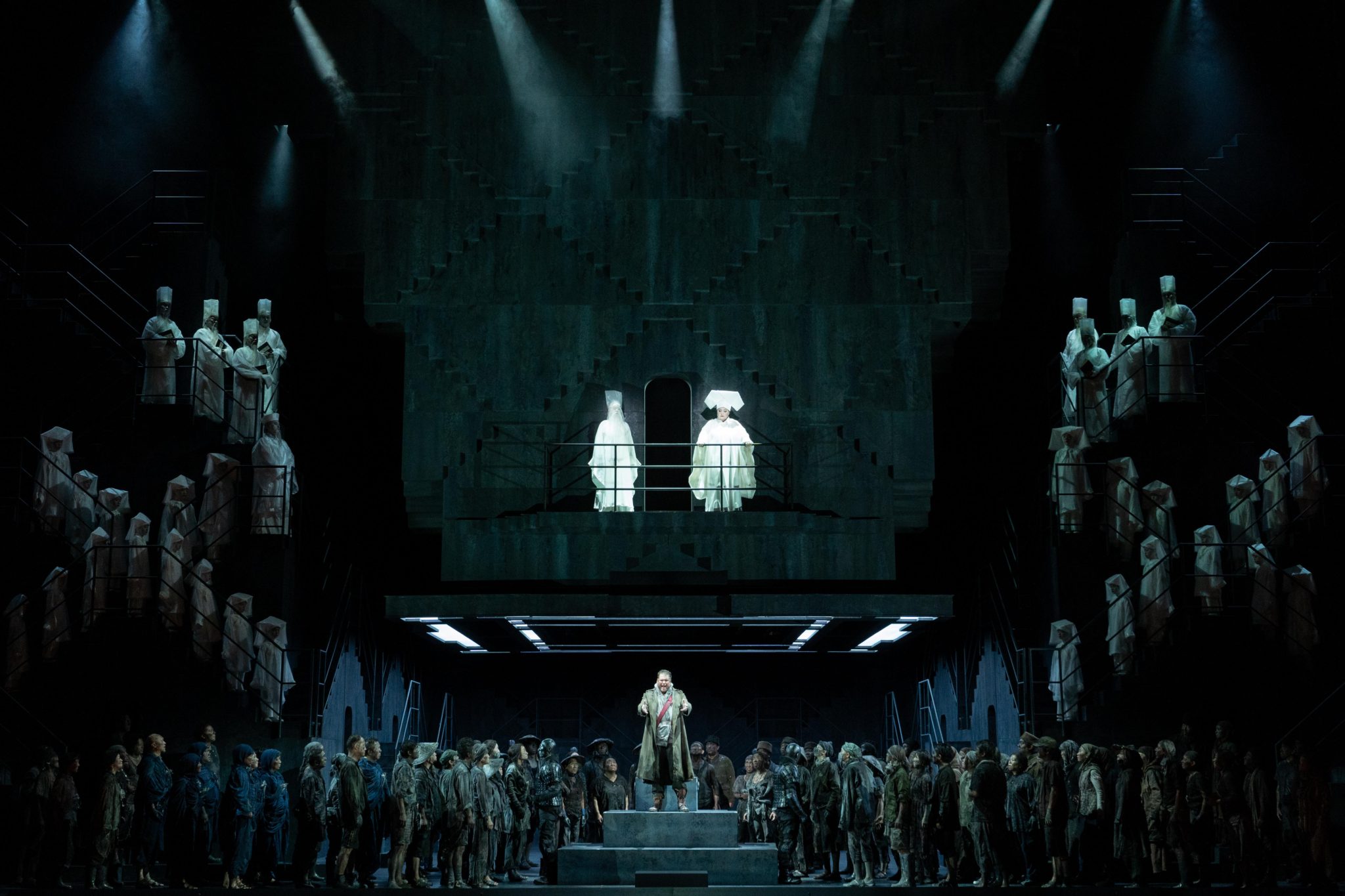

In Ollé’s version, the stage is gray, prison-like – a space far removed from the splendor of the Chinese imperial court as described in the libretto. On the walls, which enclose the stage on three sides, hang staircases and handrails like barbed wire. Down on the floor, surrounded, like prisoners, stand the gray-clad commoners. From the center of the ceiling hangs a massive rectangular structure, which casts a blinding light onto the ground beneath it. This futuristic, sci-fi-like object moves up and down solemnly, as if it was a spaceship about to land or take off. It is the heavenly place where Turandot and the Emperor live, and expresses both the Empire’s strength and, through its unrealistic symbolism, the sublimity of Heaven.

Alfons Flores’s set design uses this giant apparatus, which descends as if seeking to crush the people underneath it, to strictly separate heaven and earth from each other, thereby highlighting the oppressive power of the Empire over its subjects in brilliant fashion. The costumes produce an equally vivid contrast, with the commoners’ dirty, gray clothing set against the pure white garb worn by Turandot and the rest of the court. Ollé has worked with the same team for years now, and its shows – the equipment, lighting, costumes and other elements all come together to form an exquisite whole.

©Rikimaru Hotta

The cold Princess Turandot is courted by many suitors, but will only marry the one who can answer three riddles – failure to solve any of them will see the unworthy suitor beheaded. While all other prospective grooms lose their heads, Prince Calaf – exiled from his home country – is up to the task, and his love eventually wins over Turandot’s heart. This is the story of “Turandot” as we all know it; Calaf never doubts it was his kiss that lit the flame of love within Turandot.

But Calaf is after more than just love. At the end of the last act, with the people praising Turandot’s father, Ollé departs from the libretto by choosing not to have the Emperor appear. The people’s adoration is thus directed toward Calaf, the future ruler – indicating that Calaf is aware of the immense power he is to be granted through marriage. As large number of flower petals fall from heaven and the crowds chant their congratulations, the beaming Calaf holds Turandot’s hand; in this one blessed moment, the prodigal prince has made both beauty and power his own. However, his arrogant joy is crushed immediately after this, only seconds before the curtain falls. Ollé’s finale is poignant, eye-opening, and brilliant.

©Rikimaru Hotta

The traumatic experience of her ancestor – a princess who was taken away, raped and killed by a man – is purified and carried within Turandot, whose thirst for revenge drives her to kill the men who hope to marry her. Ollé takes this aspect beyond the realm of fantasy in the ending, in which Liù’s suicide opens Turandot’s eyes to love. Departing from the classic interpretation, he uses the princess to express a fierce anger toward machismo, thereby presenting his take on a modern-day issue.

People around the world struggling under oppression, children killed in conflicts between great powers, the #MeToo movement, indignities faced by women – hearing about these things on a daily basis makes you want to stop listening. Men can be so utterly unaware of the sad results of their selfish desires. Turandot puts up fierce resistance against Calaf’s machismo. Ollé’s superb direction mixes the sweet and beautiful tunes of Puccini – a genial melody-maker – with the bitterness of reality. Make no mistake: from now on, all renditions of “Turandot” will have to ponder how to approach the ending conjured up by Àlex Ollé.

Translated by Ilmari Saarinen

INFORMATION

Summer Festival Opera 2019-20 Japan↔Tokyo↔World

Puccini Opera "Turandot"

General Producer / Conductor: Kazushi Ono

Production: Àlex Ollé

Set design: Alfons Flores

Tokyo Bunka Kaikan Main Hall

2019.7.12 - 14

New National Theatre, Tokyo

2019.7.18, 20 -22