Christine Greiner is Full Professor at the Pontifical Catholic University of São Paulo, Brazil. She is the author of the books Readings of the Body in Japan (2015) and Fabulations of the Japanese Body and its Microactivisms (2017), among other articles and books published in Brazil and abroad.

Re-Butoooh DANCE Videology: Reenactment of Gestures, Images and Thoughts

In Japan, artistic communities have always been active during major disasters–whether they are due to natural accidents or political instability. The decades after World War II, for example, became one of the most fruitful periods for radical arts in Japan. From the 1950s to the 1970s, Tokyo became the perfect environment for risky, audience-challenging performances such as: the butoh dance of its pioneers Tatsumi Hijikata and Kazuo Ohno, the angura movement(andaaguraundo engeki or underground theatre) of Shūji Terayama, Jūrō Kara, Makoto Satō and Tadashi Suzuki, as well as performative experiences like those innovated by Zero Jigen, among many others. Most recently, the nuclear accident in Fukushima (March 2011) has also inspired very powerful reactions on stage, in art galleries, and on social media, like the self-portrait of Kota Takeuchi (Finger Pointer Worker) and his project Body is not Antibody; the soup prepared by the brothers Ei & Tomoo Arakawa with Fukushima vegetables and served during the Frieze Art Fair in London; and Chim↑Pom urban performances Level 7 at Shibuya Station. *1

However, it is important to observe that most of these artists and collectives did not manifest themselves only at the very moment when these great tragedies occurred, but also in the years that followed. In this sense, some experiences were not properly determined by specific disasters, but began to formulate fundamental questions from them, byestablishing new ways of thinking about the body, different conceptions of art, forms of life, and the ambiguous relationship between catastrophe and creation.

Butoh Dance is, of course, one of these experimental movements that actually changed the way we think about art in a global sense. Takashi Morishita, the archivist responsible for organizing Tatsumi Hijikata’s (1928-1986) digital archive at Keio University, always has made a point of stating that it is not appropriate to consider butoh “a post-war dance” as it is described in several bibliographies. Of course, butoh dance is an artistic movement that began to be conceived in this period when the precarious context of Tokyo had an enormous impact on the way artistic communities discussed body and art. However, it is essential to note other fundamental aspects such as Hijikata’s own biography and personal questions proposed by Hijikata concerning the social changes wrought by high economic growth and modernization in the post-war period. Central as well was Hijikata’s strong empathy for the work of other artists and philosophers: the painters Francis Bacon, Francisco de Goya, Wolz, Pablo Picasso and Gustav Klimt; the writer and theater director Antonin Artaud; the dancer Vaslav Nijinsky; the philosopher George Bataille; the novelist Jean Genet, among many others. All these artists were fundamental sources for Hijikata’s inspirations. Thus, artistic performances cannot be considered a simple result or effect of states of crisis. Artists have singular ways to propose debates, political gestures and strategies to deal with contemporary issues, and these differ from the approach of art critics, curators or scholars. Even when inspired by philosophers and cultural movements, artists deal with different ways of perceiving life, multiple representations of the bodies, and a generation of performative actions.

From the interview with Rina Atsumi Photo: naoto iina

Rethinking Documentation

During the Covid-19 pandemic, many artists and cultural centers (theaters, galleries, etc.) around the world, including Japan, have been thinking about new strategies of creation. One of the most interesting experiences has emerged from the possibilities of recreating archives or rethinking the concept of artistic documentation. According to new trends in performing arts in recent years, archiving is also possible through a kind of performative documentation based on past experiences to activate new creations.

In Japan, DAN or Dance Archive Network–created in 2016–has just launched Re-Butoooh DANCE Videology, bringing together short documentary films, interviews and historical performances of butoh. By creating a very original strategy, Re-Butoooh proposes a different way of dealing with artistic research and creation. It also brings into light precious research that can easily get lost or become inaccessible, especially to artists and researchers living outside Japan. According to the website, DAN is gradually making available its collections of Kazuo and Yoshito Ohno materials, of which about 25,000 items have been digitized. There include films, interviews, performances and photographs, among other materials that help us access the different contexts of butoh and its related subjects.

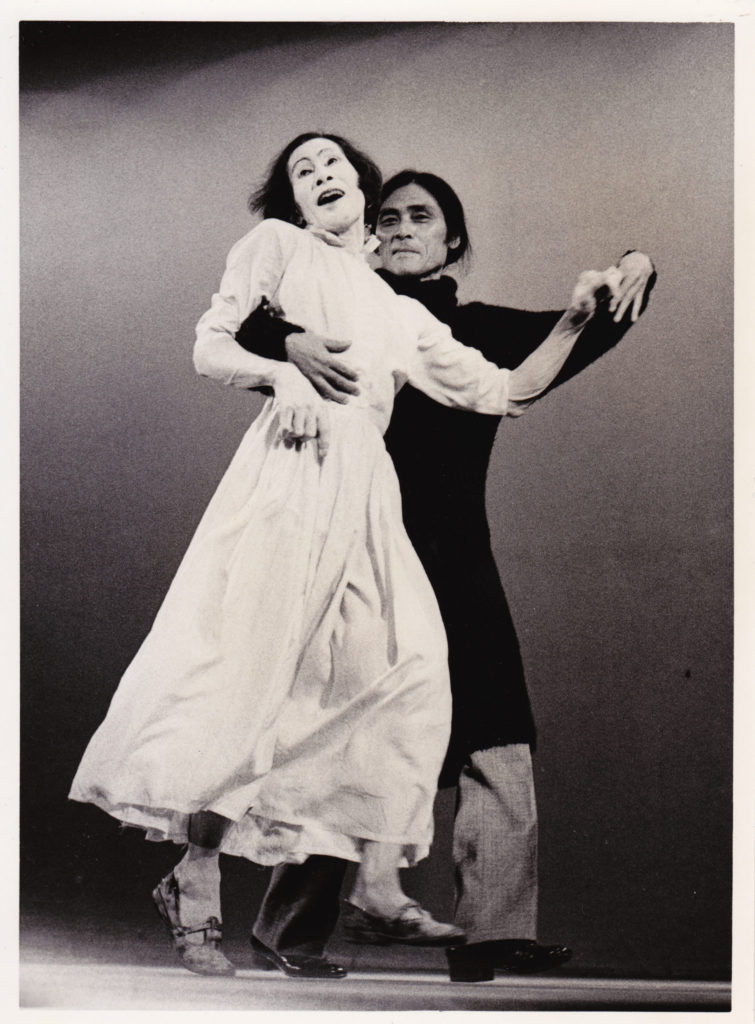

Kazuo Ohno and Tatsumi Hijikata at a curtain call Admiring La Argentina

Many of these butoh files were already previously organized and made available for some time now to those who can access them in Japan. Rich material on these great artists has been cataloged and digitized over the years by the Kazuo Ohno Dance Studio in Yokohama (and since 2016 by DAN), including flyers, films, posters, photographs, programs, books, essays, monographs, and much more. And, since 1989, Toshio Mizohata, DAN’s founder, has been planning and implementing a broad systematization of Ohno documentation. At first, the proposal was to produce digital materials related to his long career. From 1994 to 2001, several retrospectives of his work were organized, and these were complemented by film documentation and book publications.

In 1998, led by Takashi Morishita, the Hijikata Tatsumi Archive was created at the Keio University Art Center. Hijikata’s materials there include the artist’s notebooks (known as the notational butoh or butoh-fu), films, photographs, posters, programs, and numerous books on Hijikata and related fields. Previously, some of these materials had been stored at the Asbestos-kan (the former studio of Hijikata, located in the Meguro neighborhood of Tokyo). At Keio University, Morishita has added a wide range of other materials from dancers who attended courses with Hijikata and who participated in Hijikata’s shows, such as Yukio Waguri (1952-2017) and Moe Yamamoto (b.1935), among others. *2

With the rich mine of historical materials already mentioned, plus newly acquired reference materials and new works being produced by DAN itself, Re-Butoooh DANCE Videology has the potential to become an epochmaking, highly inspiring source of inspiration for butoh artists.

Over the last months, the notion of presence is changing in radical ways all over the world. The presence of screens and new platforms like ZOOM make us rethink the presence of the body. But in this situation, it’s vital to also reconsider the idea of “reenactment” because the act of reenacting is intertwined precisely with the possibilities of putting archives and bodies in motion—both together and in different contexts.

Takao Kawaguchi About Kazuo Ohno – Reliving the Butoh Diva’s Masterpieces Photo by Takuya Matsumi

A good example of this is the opening of Re-Butoooh: Takao Kawaguchi’s About Kazuo Ohno — Reliving the Butoh Diva’s Masterpieces (2013–). the first version of Re-Butoooh mixes historical examples from different periods and cultural perspectives. I consider this piece an amazing experience of butoh reenactment. Kawaguchi didn’t have any education about butoh dance, nor did he ever see Ohno perform. His process of creation started in 2013, when Kawaguchi decided to explore the possibilities of copying Ohno’s movements. This exploration was intended as a way to access the qualities of Ohno’s figure, which had become an important reference not only for Japanese dancers, but also within the history of performing arts in the twentieth century.

In his piece, Kawaguchi recovers some of the master’s dances through a very unique methodology. When he presented this work in Brazil, I had the opportunity to talk with him, and he explained during our talk, that he decided to literally copy Ohno’s movements—recorded on film and in photographic documents. Therefore, About Kazuo Ohno is Kawaguchi’s reenactment of Ohno images. These embodied images have activated multiple gestures that imitate Ohno’s movements, but also create new possibilities as Kawaguchi’s body has its own singularities.

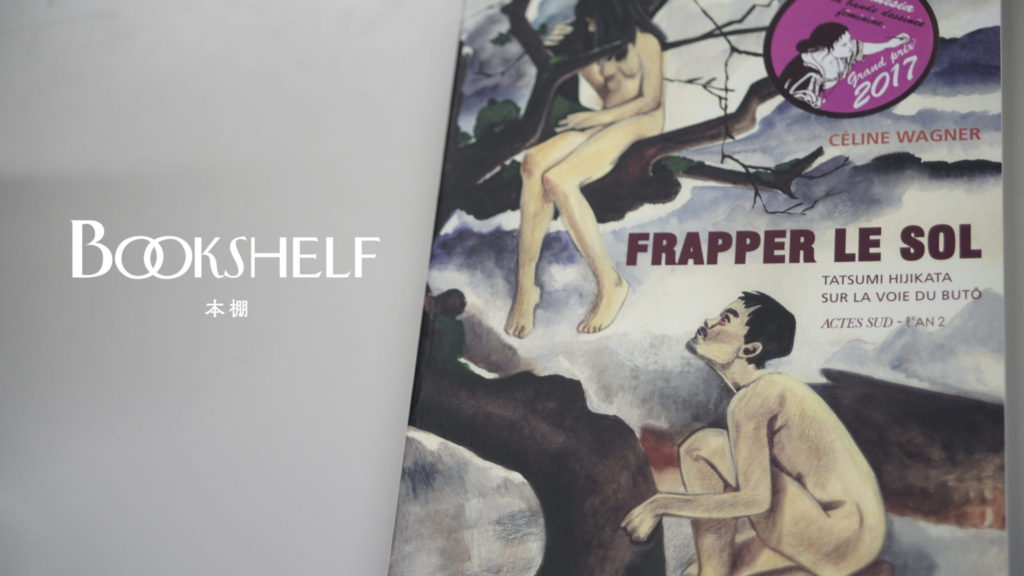

At first, we can see the encore scene from Kazuo Ohno’s Admiring La Argentina, which is one of the most legendary performances of the great master. In the clip we can see Hijikata putting a flower bouquet on top of Ohno’s head after a deep bow; and then Ohno stands at attention in the center stage and gives a military salute to the audience. Following this presentation, Re-Butooh offers us a graphic novel on Hijikata’s work created by the artist Céline Wagner and published in 2016 by Actes Sud. This can be considered a kind of fabulation of Hijikata’s research–clearly inspired by original photographs in Eikoh Hosoe’s photo book Kamaitachi. In both cases, we can identify a reenactment of important butoh subjects related, for example, to gender personification.

Céline Wagner FRAPPER LE SOL.: TATSUMI HIJIKATA SUR LA VOIE DU BUTO photo: naoto iina

The succeeding short clip introduces William Klein’s photo book TOKYO. Klein’s photographs portray three butoh artists–Tatsumi Hijikata, Yoshito Ohno, and Kazuo Ohno–who go out onto the streets of Ginza to perform in front of a crowd surrounding them. The photographs show the curiosity of a somewhat chaotic metropolis on a pre-Olympic afternoon in 1961.

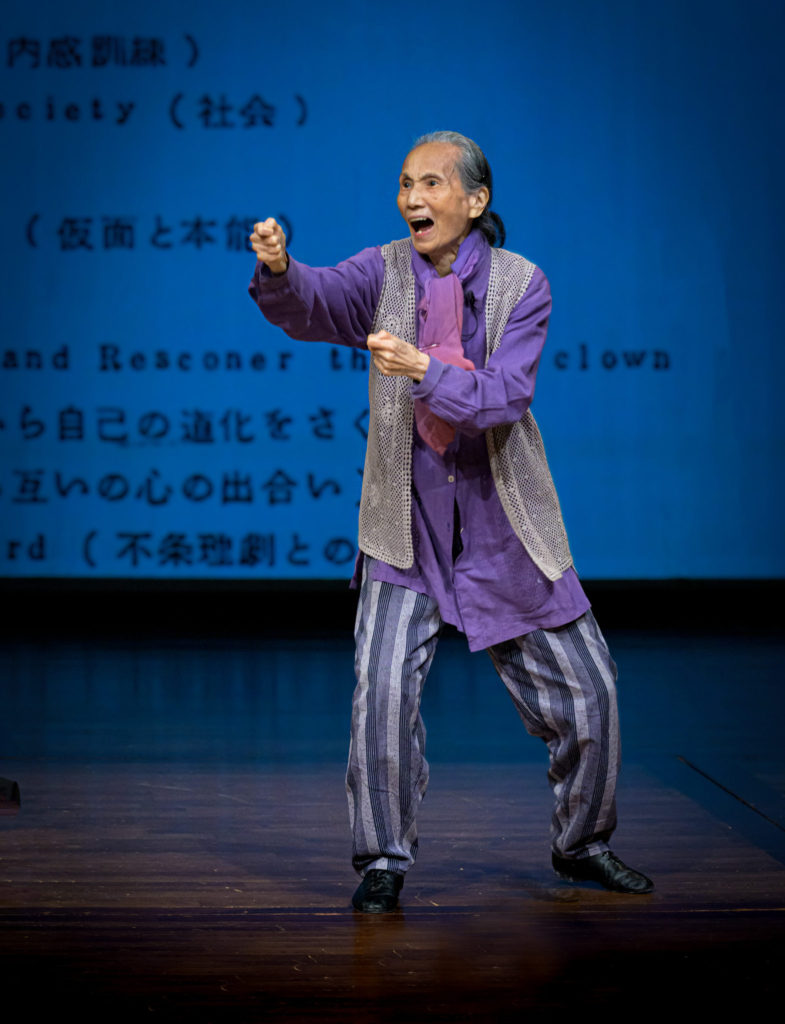

Re-Butoooh also presents with the pioneers of modern Japanese dance, Takaya Eguchi and Misako Miya, with their perfomances from the late 1930s; a performance from 2016 in Paris by contemporary dancer Mikiko Kawamura; the costume creation for Yoshito and Kazuo Ohno for the piece Water Lilies (1987), and a conversation with Yoshito’s wife, Etsuko, who organizes costumes at the Ohno studio; and finally, the world of mime performer Mamako Yoneyama. Considered one of Japan’s mime pioneers, Mamako Yoneyama studied with Eguchi and Miya in order to learn modern dance, and also with Kazuo Ohno. She spent some time in the US to master the art of pantomime. Later she went home and established the genre in Japan. Eventually, butoh dancers became interested in mime as a technique to create representations of “other bodies”. So, it was interesting to include Mamako Yoneyama as part of this historical overview.

Mamako Yoneyama in All About Zero Photo by Koichi Tamauchi

Mikiko Kawamura LA FLEUR ÉCLÔT EN ENFER Photo by Cédric Duron

This cartography of different experiences of butoh dance or, in a broader sense, this cartography of complex movements of thought, urban performance, visual culture and dance experiences that composes this videology offers a way of mapping both artists from different fields (not only dance) and researchers interested in knowing more about the butoh experience and its digital reverberations. The plurality of images, films and narratives organized by Re-Butoooh DANCE Videology can also be understood as a curatorial proposal to trigger new possibilities of movement and thought.

In several ways, the contemporary dance experiences appear far from butoh. At first sight, some issues that inspired the works of Kazuo and Yoshito Ohno as well as those proposed by Hijikata have changed in a radical way. However, there are many questions that continue to be relevant and powerful to several artists working both in and beyond Japan. For example: the fragile borderline between life and death still represents an essential topic of research, as well as political subjects related to the diversity of sexualities, the denial of eugenics and power relations. These are but some among the many other important traces of butoh history.

The first issue of Re-Butooh DANCE Videology is still available for viewing on the Internet for free. As a foreign researcher and professor, I’m curious to see the next issue of Re-butoooh, where I’ll be looking for the reenactment of fundamental ingredients to feed our historical curiosity, and that can scramble habitual categories of custom and thought as well as refocus our perception of life and movement.

Note:

1) In 2018, the Mori Museum in Tokyo proposed the exhibition Catastrophe and the Power of Art. More than forty artists and groups were part of this important overview of the possible connections between art, disaster, aesthetics and politics. See https://www.mori.art.museum/en/exhibitions/catastrophe/

2) Waguri created the Butoh-Kaden, his own notational butoh based on Hijikata’s methodology, and Moe Yamamoto transcribed Hijikata’s notational butoh in the book Costume en face, a primer of darkness for young boys and girls, translated by Sawako Nakayasu, and published in 2005.

References:

Baird Bruce and Rosemary Candelario, (eds.) The Routledge Companion of Butoh. New York: Routledge, 2018.

Lozano, Jonathan Caudillo. Cuerpo, Crueldad y Diferencia en la danza butoh. Ciudadel Mexico: Plaza y Valdez, 2016.

Morishita, Takashi. Hijikata Tatsumi’s Notational Butoh, an Innovational Method for Butoh Creation. Tokyo: Keio University Art Center, 2015.

Pagès, Sylviane Le Butô en France: malentendue et fascination. Paris: CND, 2017.

INFORMATION

Re-Butooh DANCE Videology

Sponsor: NPO Dance Archive Network

Composition / Direction / Video Editing: Naoto Iina

Public relations /Marketing /Text: Toshio Mizohata, Yurika Kuremiya

Translation: Mai Honda