Toshiro Inaba, M.D., Ph.D. Born in Kumamoto in 1979. Cardiologist and Assistant Professor at the Department of Cardiovascular Medicine of the University of Tokyo Hospital from 2014 to 2020. Since April 2020, holds the roles of Head of the Department of General Medicine at Karuizawa Municipal Hospital, Associate Professor at the Shinshu University Research Center for Social Systems, Visiting Researcher at the University of Tokyo Research Center for Advanced Science and Technology, and Visiting Professor at the Tohoku University of Art and Design. Inaba was also appointed Artistic Director of the 2020 Yamagata Biennale, and is involved in home medical care and mountain medicine. He engages in active discussion with professionals in a wide range of fields in order to bring about new medical and social solutions. His publications include “Inochi o Yobisamasu Mono” (Anonima Studio), “Korokoro Suru Karada” (Shunjusha), and “Karada to Kokoro no Kenkogaku” (NHK Publishing). Website: https://www.toshiroinaba.com/

“Okina” (Kazufusa Hosho) Photo(c) Seiichiro Tsujii

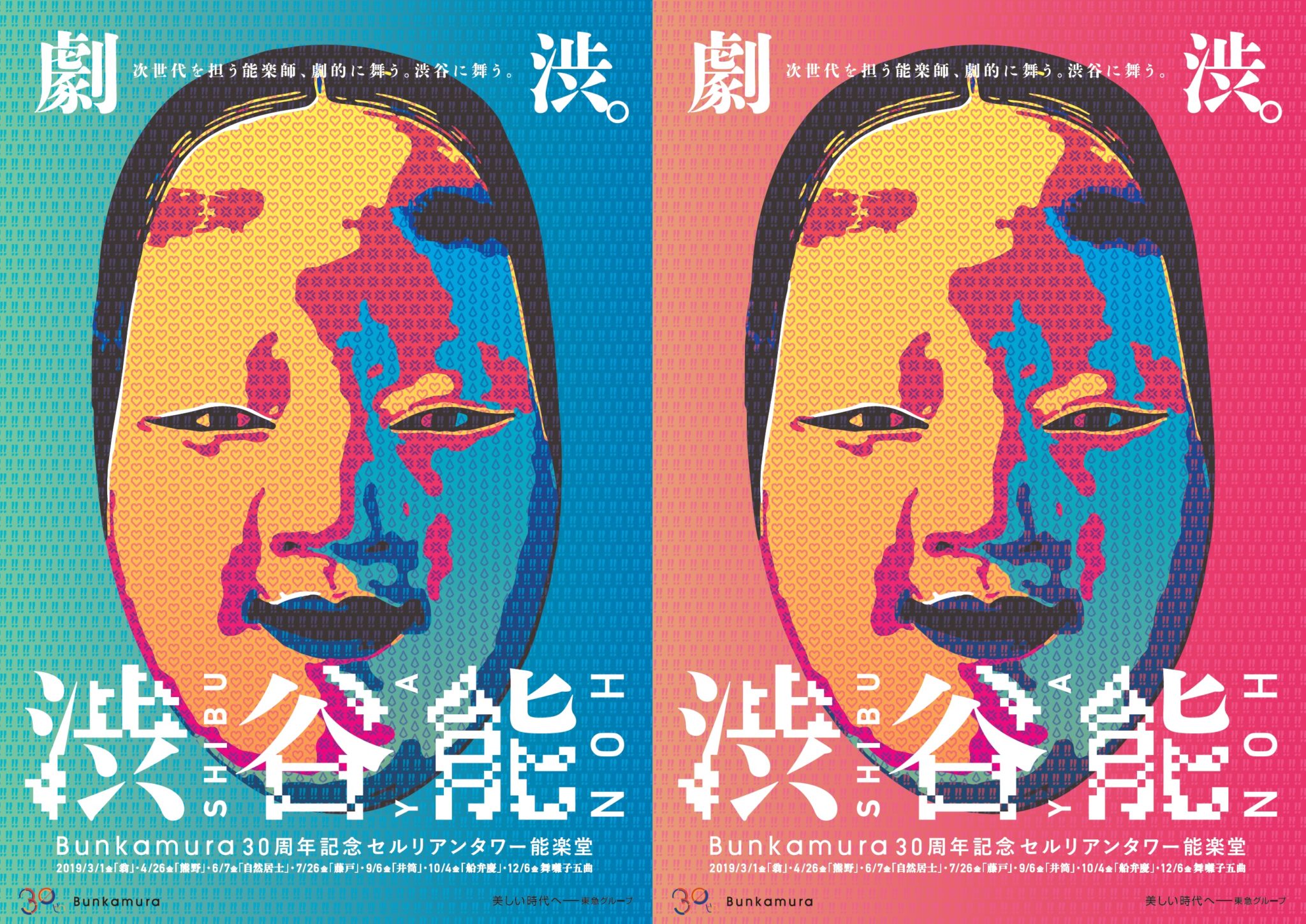

“Shibuya Noh” is a new project taking place at the Cerulean Tower Noh Theatre. It features elements that differ from those of regular Noh performances, so I would like to start by discussing these. First, Shibuya Noh is a series of noh plays put on by a group of young performers who hail from several different schools. The world of Noh is separated into schools (for example, the five shitekata, or main performer, schools are Kanze, Hosho, Komparu, Kongo and Kita), which are usually kept apart — members of different schools rarely appear on the same stage. The fact that Shibuya Noh is centered on young performers is equally noteworthy. Dancers and the like are perhaps considered to be in their prime in their 40s, but in the world of Noh, their artistic abilities are scrutinized beyond the age of 60, even 70. In other words, fledgling artists have a seemingly endless road in front of them. For that reason, it is extremely rare to see a play like Shibuya Noh, which is built entirely around young performers. But these artists are also exceptionally skilled, and watching them in action is a surprising testament to the depth present in the ranks of Noh, which truly is an art form maintained by practitioners both young and old. Second, the Shibuya Noh program is designed to be as approachable for first-timers as possible — a style that is reflected in the themes of the plays — and structured with the entire year’s performances in mind. Each set of shows has a specific theme, such as “celebration”, “affection for one’s parents”, “justice”, “absurdity”, “love” or “battle”, testifying to the great variety present in Noh. The third distinguishing feature of Shibuya Noh is that it is entirely crowd-funded. To protect and disseminate the essence of Noh, these young performers have placed particular emphasis on sharing the process of creating shows with the audience. The result of that process is Shibuya Noh and all its distinguishing features.

Most people don’t know much about Noh. To me, that is hardly surprising; after all, this art form is more ritual than regular entertainment. In our age, with rituals falling by the wayside, understanding their significance is of course difficult. That is exactly why us members of the audience should participate in Shibuya Noh as co-creators, asking ourselves what rituals are to us.

“Jinen-koji” (Tamon Sasaki) Photo(c) Seiichiro Tsujii

The first evening of shows (March 1) featured “Okina” (by the Hosho school), a truly ritualistic play. In it, a performer appears with his face visible (hitamen), and ascends onto the stage to hold up a Noh mask with both hands. He then puts it on to become an okina (elderly man), and starts mai, dancing to pray for peace throughout the land and an ample harvest. Noh was originally an art form performed for the gods, so all participating co-creators are required to join in prayer to these deities.

The second evening (April 26) centered on “Yuya” (Komparu school), a play based on a reinterpretation of the “Tale of the Heike”, when dark clouds have already begun to gather over the fortunes of this illustrious family. When all the story’s characters gather for hanami, one that may well be the last blossom-viewing they attend in this life, the life and death expressed by the blooming trees and their falling petals resonate with the fate of the individual characters and their clan. Even flowers in full bloom are easily swept away by rain, and people familiar with such a scene feel in it the impermanence of things and fate. The beauty of spring is contrasted with the dark depths of the soul. This comparison of external light and internal shadows drives viewers to recall their own experiences, thereby capturing their hearts.

The third part (June 7) of Shibuya Noh featured “Jinen-koji” (Kita school), the story of the eponymous hero helping a child who has sold herself to a slave dealer. The convictions of Jinen-koji clash with those of the human traffickers, but this discord is settled not through force, but in an aesthetic manner by way of overwhelmingly beautiful dancing. The use of beauty instead of strength to solve a conflict hints at the future Noh can help bring about. With Shibuya having been in the headlines for “compensated dating” a while back, seeing “Jinen-koji” performed in the neighborhood reminds us how its themes continue to resonate in the present.

In Part 4 (July 26), the featured play was “Fujito” (Hosho school). Sasaki Moritsuna, a general of the Genji samurai clan, meets an old woman at Fujito (present-day Kurashiki in Okayama Prefecture). She laments how her son was killed by a certain warrior. In fact, Moritsuna had convinced a young fisherman to teach him how to pass to a distant island on horseback by riding over hidden shallows, and killed the lad to keep this passage secret. The samurai is visited by the fisherman’s ghost, but manages to appease him by hastily hosting a memorial service so that his spirit can cross over into the afterlife. In the “Tale of the Heike”, this story is recounted as one of Moritsuna’s legendary exploits, but “Fujito” reminds us that such heroism is premised on the killing of nameless innocents, thereby shining a light on the death and sorrow ignored by history.

left) “Yuya” (Masahiro Nakamura) Photo(c) Seiichiro Tsujii

right) “Fujito” (NorimasaTakahashi) Photo(c) Seiichiro Tsujii

The rest of the program consists of Part 5 (September 6) featuring “Izutsu” (Kanze school) and Part 6 (October 4) with “Funabenkei” (Kongo school), before Shibuya Noh comes to a close on the seventh and final evening (December 6), when each of the five schools will perform a maibayashi (an about 20-minute performance of “highlights” from a specific Noh play, featuring a shite as the dancer, in addition to chorus singers and performers playing instruments).

Noh plays often include dead characters who converse with their living counterparts. The meaning of this appears to be that listening closely to what the dead have to say, and making use of their messages in the present, are the only things that those who have left us hope for. Above, I mentioned that Noh is closer to a ritual than it is to entertainment, and rituals value the experience above all else. That is because rituals also work as “waterways” of the soul. They saturate the dry parts of our hearts and minds and help circulate any excess “water”, reaching deep into our souls. Rituals also connect the living and the dead.

We wake up and go to bed every day, and our bodies and souls are updated in the fleeting moments between sleep and wakefulness. The world of Noh has always paid great attention to these states of unclear consciousness, because along such dreamlike paths, the living and the dead can interact freely, unbound by the constraints of time and space.

Shibuya Noh aims to connect the past, present and future with new threads, and is on track to present to us the significance of the place-bound experiences Noh can provide.

INFORMATION

Shibuya Noh

2019.3.1 / 4.26 / 6.7 / 7.26 / 9.6 / 10.4 / 12.6

Bunkamura 30th Anniversary at Cerulean Tower Noh Theatre