Toshiro Inaba, M.D., Ph.D. Born in Kumamoto in 1979. Cardiologist and Assistant Professor at the Department of Cardiovascular Medicine of the University of Tokyo Hospital from 2014 to 2020. Since April 2020, holds the roles of Head of the Department of General Medicine at Karuizawa Municipal Hospital, Associate Professor at the Shinshu University Research Center for Social Systems, Visiting Researcher at the University of Tokyo Research Center for Advanced Science and Technology, and Visiting Professor at the Tohoku University of Art and Design. Inaba was also appointed Artistic Director of the 2020 Yamagata Biennale, and is involved in home medical care and mountain medicine. He engages in active discussion with professionals in a wide range of fields in order to bring about new medical and social solutions. His publications include “Inochi o Yobisamasu Mono” (Anonima Studio), “Korokoro Suru Karada” (Shunjusha), and “Karada to Kokoro no Kenkogaku” (NHK Publishing). Website: https://www.toshiroinaba.com/

Photo credit: Hidemi Seto

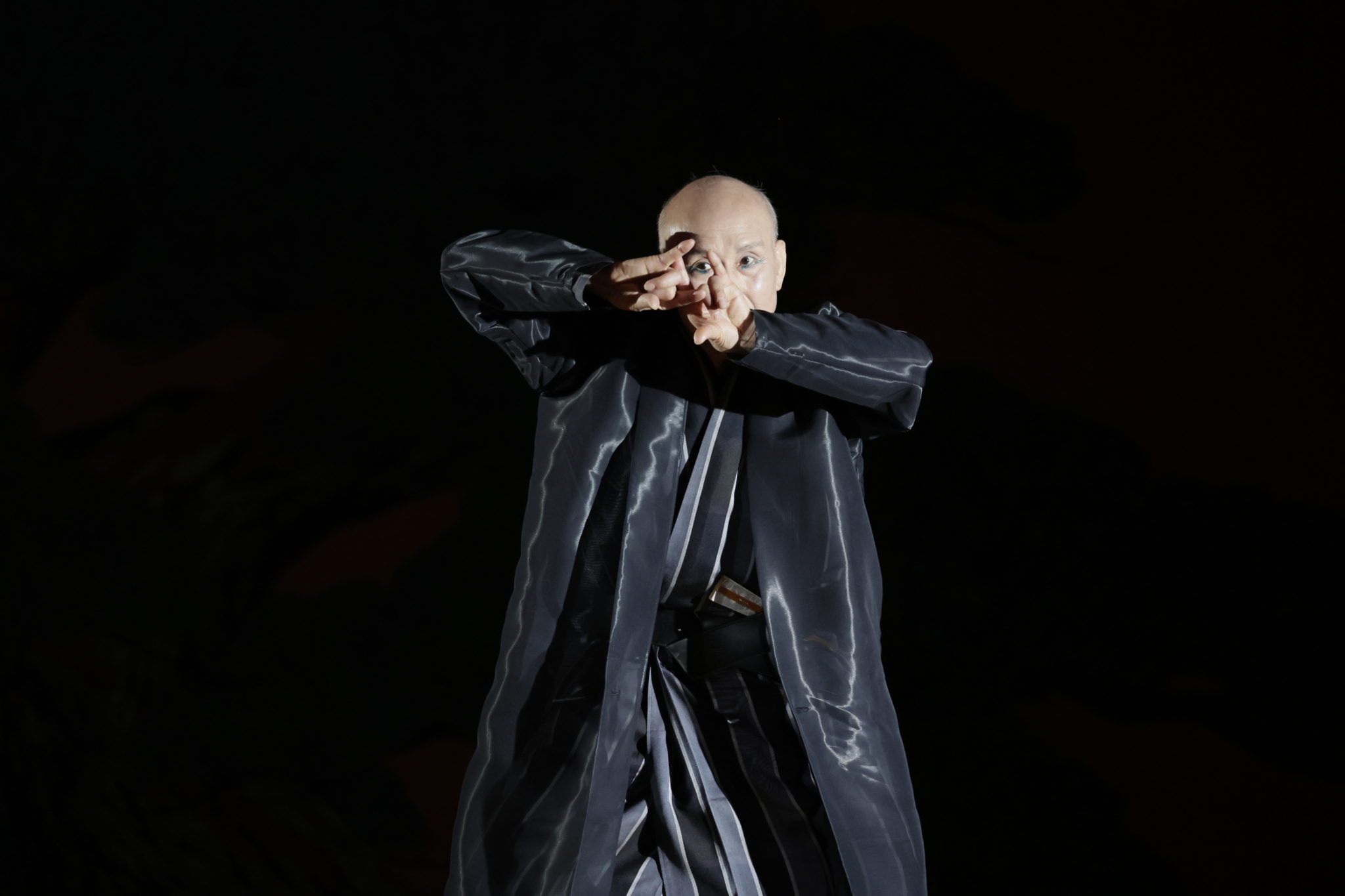

Tradition and Creation * vol. 12: “Yabu no Naka,” organized by the Cerulean Tower Noh Theatre and inspired by Ryunosuke Akutagawa’s short story of the same name, was an ambitious performance. “Yabu no Naka” (translated as “In a Grove” or “In a Bamboo Grove”), is a story about how the truth about a death disappears, “into the grove,” as it were. By placing darkness and mystery at the center of the story, the performance indirectly appeared to raise questions about the courage and determination of each one of us to face life’s hard truths.

Photo credit: Hidemi Seto

Presented by five dancers, the performance made for a strange and wonderful experience that was both mythical and interspersed with periods of mourning. In “Yabu no Naka,” the truth about the death the story revolves around disappears “into the grove” because each of the five characters’ claims and viewpoints are different. However, it can also be said to raise doubts about the very way in which we casually assign cause and effect to various events. There are no supporting roles in the performance; all the characters are protagonists. The same could even be said for the fluorescent lamp on the stage (akin to the hanging bell from the ceiling in the Noh play “Dojoji”), which through its repeated and strange flickering appeared to represent the wavering sense of reason in the characters involved in the drama, as well as a contemporary version of the sun or moon, which have watched over humanity since time immemorial.

The particular space of the Noh theater itself is akin to the inside of a bell in the afterlife that one temporarily enters. The audience in such a theater, like the waki (supporting actor) in a Noh play, as it were, becomes a participant in the performance, a link between the utsushiyo (the actual world) and the tokoyo (the eternal world). In this performance, not only the dancers but also the music and costumes were deeply integrated into the work. As the particles that made up that space, like vibrations, these elements greatly enhanced the performance’s depth.

The five dancers seemed to be engaged in dancing as well as in acting all while appearing to be figures When humans are placed in the ultimate situation of standing face to face with death, they at times form connections, express sympathy for each other, and bring about harmony, while at other times they divide, obstruct, and destroy each other. The dancers expressed such psychological coalescence and division as if by drawing figures of sacred geometry.

Photo credit: Hidemi Seto

What is the meaning of life? Humans have been given brains and feelings so that we may live better lives. Kindness and sorrow, joy and anger—they share the same purpose. All of them stem from the body, heart, soul, and life we are born with. However, us humans do not necessarily truly know ourselves. We can’t handle ourselves very well. That’s why basic human instincts, our true nature, which in a state of crisis come out like a photo negative, burst into the open through our bodies. Dance is the expression of such extreme psychological states through bodily movement alone. The movement of the soul becomes the movement of the body, body and soul become one, the bodies and souls of onlookers fuse even with the stage, joining together. The emotional movement of and connections between the dancers and the audience lead to a requiem for the dead.

A part of the performance evoked a ritual of mourning for someone who has died, and this made a particularly deep impression on me. That is because I think the experience of death is what first compelled humans to create art. Life is the process of accepting the unacceptable, and that in itself is the stimulant that drives the expansion and growth of human consciousness. The most symbolic phenomenon here is the reality of living things dying, and confronting death is what gives birth to rituals and rites, as well as culture and civilization, which extend into dance. Dance as the movement of the human soul and body, clothing that enhances its attraction, sound that subconsciously lends the scene direction, a light in the sky like the master of time that watches over humanity, and an audience sincerely keeping its eyes on the stage—that entirety itself is a ritual for the repose of the dead, as well as a continuation of life. From start to finish, the performance made for a mythical experience that unfolded through people and things colliding and merging, all while maintaining an appropriate distance from each other. Concentrating their spirit, the dancers moved unrelentingly, as if praying. Us onlookers took it all in like an encounter with the sacred, before returning to the endless loop of daily life.

Photo credit: Hidemi Seto

I’d like to end by quoting the preamble of the Basic Act on Culture and the Arts (enacted in 2001 and revised in 2017).

“It is the people’s unchanging desire to create and enjoy culture and the arts, and to find joy in living in a cultured environment. Culture and the arts nourish people’s creativity and enhance their ability to express themselves, provide an environment for people to connect with each other and to understand and respect each other, aid the formation of a generous society that accepts diversity, and contribute to world peace.”

I believe in the power of these words from the bottom of my heart. No matter how harsh their circumstances, our ancestors never forgot the joy of being alive. That is why culture and the arts have been passed down amid the forces of tradition and creation. That flame is distributed through the stage into all of our souls, which it illuminates. I am deeply grateful to the performers of “Yabu no Naka,” which made me feel such fundamental, raw joy, and to all those working behind the scenes of culture and the arts. In our age of turmoil, the time spent experiencing such wonderful performances together is precious above all else.

Photo credit: Hidemi Seto

*“Tradition and Creation” is a performance series providing answers to the question of how contemporary dance choreographers interpret and utilize the traditional Japanese space that is the Noh theater.

INFORMATION

Tradition and Creation vol. 12: “Yabu no Naka”

January 13-16, 2022

Original text: Ryunosuke Akutagawa

Director and choreographer: Yasutake Shimaji

Performers: Reijiro Tsumura, Hana Sakai, Kenta Kojiri, Yasushi Shoji, Yasutake Shimaji

Costume design: matohu

Music: Yuta Kumachi

Lighting: Azusa Seto (balance,inc. DESIGN)

Acoustics: Naoto Oka

Stage director: Daijiro Kawakami

Organization and production: Cerulean Tower Noh Theatre

https://www.ceruleantower-noh.com/

Planning and production: Studio Architanz

http://a-tanz.com/