She graduated from Tama Art University (Craft Department, Glass Course) with a bachelor’s degree in Fine Art. After graduating, she joined metaPhorest (biological / bio-media art platform)in the Laboratory for Molecular Cell Network & Biomedia Art, at Waseda University as an artist and visiting researcher. Since 2021, she enrolled in the Doctoral Program in the Graduate School of Interdisciplinary Information Studies, The University of Tokyo (Yasuaki Kakehi Lab.) She’s creating artworks using scientific glass production techniques, organisms, organic matter, image analysis, etc.. She’s main themes are to reconsider the borders of nature/society, human/non-human, and the indivisibility of the expresser and the object of the expression at the interdisciplinary viewpoint.

When writing, I sometimes wonder how to express my own experiences and feelings. The normative awareness that persuasive expression requires using third-person descriptions is strong, as is the worry that even writing about experiences in the first person will not accurately convey the reality and vividness of what was going on inside me at that point in time.

Such concerns, however, are readily dispelled by “Ecosophic Art.” The main thrust of the book consists of introductions to specific exhibitions and art projects which the author, Yukiko Shikata, has been directly involved with or has viewed, and discussion of their ideological positioning. In terms of its own ideological standpoint, the book draws on Félix Guattari’s concept of three ecologies, which proposes the necessity of an ecology not only of the environment, but also of society and of the mind. Various events and ideas are spun together based on the concept of an information flow, which makes it possible to capture and express each ecology on the same level, despite them being considered dissimilar on a material level. The title concept of “ecosophic art” is derived from ecosophy, a term coined by Guattari in “The Three Ecologies” that joins together ecology and philosophy.

At first, I was confused by the exclamation marks that appear here and there in the text. The experience made me aware of the norms of written expression and communication that bind me, and this feeling of strangeness appeared to invite my mind to a place of greater freedom.

The author’s descriptions of her own experiences, which seem to be bursting with raw joy, are the very language of the ecology of the mind, and the way her critical discussion of social and environmental ecology, woven together across the humanities and natural sciences, is connected to this language invites the reader into the midst of an information flow of the three ecologies. This dynamic yet smooth back-and-forth is backed by the author’s vast experience and knowledge. Shikata has been working energetically as a curator since the early 1990s, focusing on media art both in Japan and abroad, and the narrative of her real-life experiences reads as living history. When I entered Tama Art University in 2012, she was already a well-known curator who also taught at the university. The artists and art projects the author discusses from the 2010s onward are familiar to me, and vividly evoke my own experience of starting out as a clueless art student and gradually becoming able to see the world, learning to walk on my own two feet as an artist while being influenced by senior artists and their works. For example, Hideo Iwasaki, who is introduced in the book as a bio-artist and life scientist, is the organizer of metaPhorest, a bio-art platform that I was involved with after graduating from Tama Art University and that has greatly influenced my thought and work. Shiori Watanabe, who curated the exhibition “Toto-tarari-tararira-tarari-Agarira-raritou,” is an artist friend with whom I have exhibited together in group shows, and with whom I sometimes discuss ideas for collaborative projects, although these haven’t yet been realized. I occasionally heard about the baby she was carrying at the time of the exhibition mentioned in the book. “Ecosophic Art” boldly describes the inseparable connection between activities generally classified as either public or private; the process of birth, as well as those of art- and exhibition-making.

Maki Ohkojima “Perforated Spiral” 2021

The book consists of three main chapters: “Chapter 1: Signposts—Tracing the Origins of Ideas,” “Chapter 2: Into the Field—Ecosophic Art Theory,” and “Chapter 3: Emergence—The Outlook for Art Commons.” The second chapter, “Into the Field—Ecosophic Art Theory,” is divided into sections on the forest, life, vortexes, water, earth, power, and electrons, each with introductions of specific art projects related to the theme at hand.

The most impressive work in the “Life” section is Maki Ohkojima’s “Perforated Spiral” (2021). Born in 1987, Ohkojima is a Tokyo-based artist whose theme of expression is “life in a tortuous cycle of entanglement, entanglement and fraying.” The installation “Perforated Spiral,” exhibited at the Kadokawa Musashino Museum, is shaped like a rhizome and features a meta-structure that connects as nodes the paintings and objects that make up Ohkojima‘s exhibition space. While Ohkojima’s works are primarily expressive in terms of production technique, with images of life and nature drawn from her own imagination, she describes the shape of “Perforated Spiral” as a transcription of pathways created by water poured into a fill and eroding the soil. This reminds us that the realm of Ohkojima’s own imagination, which can be considered part of the ecology of the mind, as well as her neural networks, are patterned by the ecology of the environment—just like water eroding soil.

Keiko Kimoto “Imaginary Numbers” 2003

In contrast, the “Vortexes” section highlights the work of Keiko Kimoto, an artist who uses Apple’s Macintosh, one of the first personal computers from the 1980s, to generate two-dimensional works with programs that use nonlinear dynamical equations. Kimoto taught herself programming in an attempt to erase her own form of artistic expression, a pursuit that in a sense contrasts starkly with Ohkojima’s approach. I remember encountering her signature work “Imaginary Numbers” when I was a university student, and being impressed by the tension in the work—clearly distinctive even in today’s world, full of mathematically generated forms of expression—as if I had glimpsed the secrets of the laws of nature. Reading “Ecosophic Art,” I learned that Kimoto has recently been printing out lines generated by equations on washi paper and tracing them with iwa-enogu mineral pigments used in Nihonga painting. This seemed to me an interesting counterpart to Ohkojima’s “Perforated Spiral,” created by drawing on the natural laws of earth and water to contrast with her own technique of expression. In the words of Hideo Iwasaki, quoted in the book, the ecologies of the mind and the environment are inextricably linked like in a Möbius loop, the structure of which is like looking at the two sides of its knot both from the front and back.

Goro Murayama “Generative Rectangle- Golden Ratio V” 2021 photo by Goro Murayama

Also in the “Vortexes” section, Goro Murayama is introduced as an artist who has taken up and developed further through his art the concept of autopoiesis, a term coined by Chilean biologists Humberto Maturana and Francisco Varela to describe the first-person perceptions of a living organism and objective, scientific descriptions of the world as two sides of the same coin. In his art, Murayama combines brush strokes that reflect his own physical sensations with mathematical algorithms. “Support Dynamics” (2021), the project featured in this book, is a painting in which similar patterns are drawn on a canvas that has been divided using the Fibonacci sequence to form a golden spiral. The similarity of each drawing makes the composition look like a cutout of a fractal structure. I was struck by the author’s comment that in our world that unfolds from the micro to the macro, only the part at the scale of the human body is visualized and materialized. Here again, we see the intertwining of multiple ecologies.

from “Ecosophic Art”

The artists and art projects introduced in this book are intertwined with the author’s personal experiences, an approach that vividly dispels the notion of “purified” artists and artworks that exist independently of society or nature. The works depicted in the book are not ones entrusted with a cause to save the world, nor are they ones that are isolated from society to ask big questions about the nature of art. Instead, they are instances of life itself, existing firmly as nodes in an ecosystem of the mind, society, and the environment.

The author’s worldview is rooted in the rhizome concept proposed by Deleuze and Guattari. It’s a metaphor for a network-like system in which peripheral branches can be connected to each other, being the antithesis of a hierarchical system in which the trunk and branches are differentiated like on a tree. Rhizome became a buzzword in contemporary thought and art circles in the ’80s and ’90s, and is sometimes discussed as a worn-out concept. In reality, however, hierarchical systems still possess an overwhelming advantage when it comes to the efficient management of a complex modern society and the mass production of things that are reproducible from an engineering standpoint. In “Ecosophic Art,” the rhizome and information flow concepts are carefully connected to actual art projects, letting the reader see how ideas, as opposed to being consumed as catchphrases, link to living phenomena, experiences, and materials. There, new meanings continue to be generated, and one can feel the energy that re-weaves and gradually heals the network, which occasionally grows at non-lifelike speed.

The experience of reading this book can be a moment of renewed joie de vivre for anyone who despairs of all the divisions that slice and dice our world and feels personally compelled to exist as one of these severed “things.” I hope that many readers, together with the artists in this book, will have the opportunity to experience the dynamism of the information flow that exists beneath these divides, and accept the invitation into its vortex of energy that evokes latent ties even among seemingly disconnected things.

Translated by Ilmari Saarinen

INFORMATION

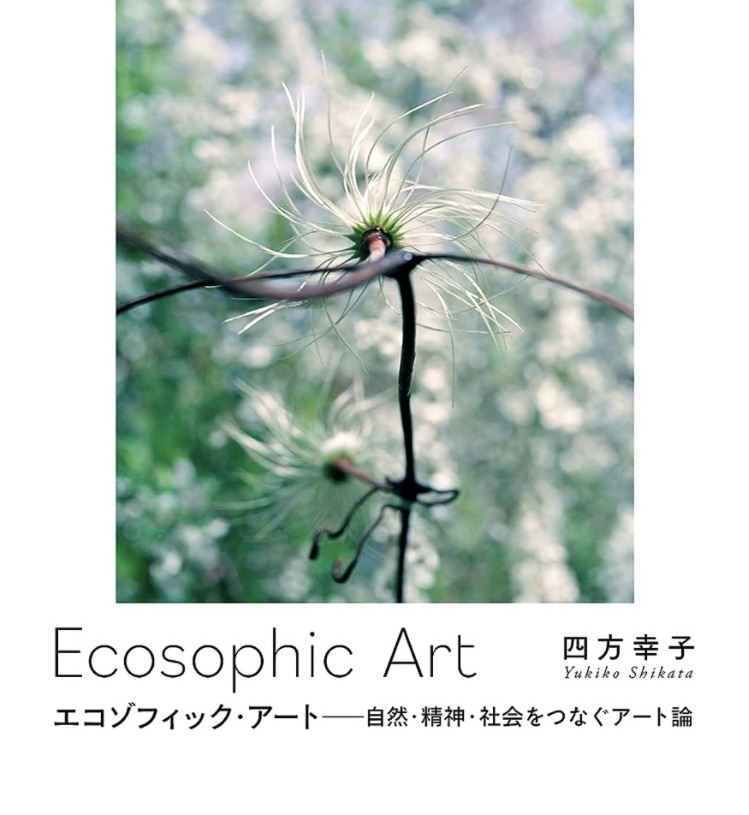

“Ecosophic Art”

Author: Yukiko Shikata

Published by: Film Art Publication

Date of publication: 2023.4.26