Born in Tokyo. Graduated Keio University Faculty of Literature, Department of Philosophy, aesthetics and art history major. Since 1990s, She has been at the forefront of the Japanese art scene as a writer / art journalist / art producer. 2003 spring, launched an art bar TRAUMARIS in Roppongi, was moved to Ebisu NADiff building, as an alternative space TRAUMARIS where art exhibitions, live performances, food and drink can be enjoyed. After closed the space, is currently involved in various art activities beyond the boundaries of the genre as an art producer. A jury for Yokohama Dance Collection’s competition from 2011 to 2016. A producer of Dance and Nursery!! Project since 2016. Established RealJapan project as a co-director. http://www.traumaris.jp Photo by Mari Katayama

Apichatpong Weerasethakul《Motion Pictures Project at Mae Ma School》 photo: Chie Sumiyoshi

A skin-permeating artistic remedy

In December of last year, I visited the Thailand Biennale, Chiang Rai 2023, which is taking place in the country’s northern borderlands. This international art showcase generally takes place every two years and is now marking its third edition, following previous festivals in Krabi and Nakhon Ratchasima (Korat).

Drawn by the charm of Chiang Mai, the ancient capital of northern Thailand, I had visited the city several times before. After being held back by the Covid-19 pandemic, I was finally able to return in the year the Biennale opened. It’s a three-to-four hour drive from Chiang Mai to Chiang Rai and Chiang Saen, where the main venues are located, and you need more than an hour to travel between the two cities. This makes getting around by yourself rather challenging, but together with a couple I’m friends with and who have been running a business in Chiang Mai for many years, we planned a two-day trip, and I was fortunate enough to have them drive me around the major exhibition sites.

Wat Rong Khun (White Temple) photo: Chie Sumiyoshi

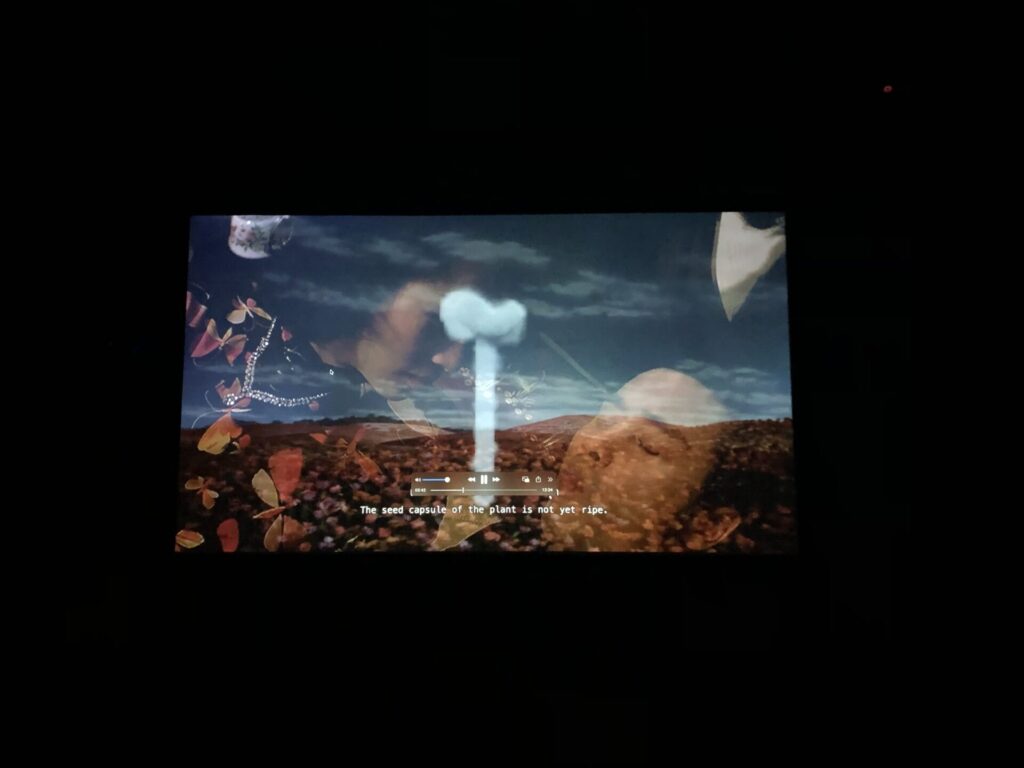

Korakrit Arunanondchai《2012-2555, 2556, 2557》2012 – 15 photo: Chie Sumiyoshi

Our first destination was Wat Rong Khun, better known as the White Temple. This historic place of worship, now a very popular tourist site, was revived by the renowned local artist Chalermchai Kositpipat, who purchased the temple himself and turned it into a theme park painted in white and gold. The kitschy, sparkling temple architecture that suddenly appears along the streets makes for a scene reminiscent of Las Vegas rising up in the midst of the desert. Decorative sculptures take up every nook and cranny, but all around them artisans who look like moonlighting art students are adding to the proliferation. Is this the Thai version of the Sagrada Familia? (Apparently they’re aiming to complete the temple in 2070.) Temples are a familiar part of daily life in Buddhist Thailand, but while remaining places of worship, they’re generous enough to embrace even individuals’ desire for expression. However, donations for the construction of the temple are limited to a maximum of 10,000 baht in order to avoid control by large sponsors—a spirited policy that’s also in line with ours here at RealTokyo, which doesn’t accept ads.

A gallery in the back houses a piece by Korakrit Arunanondchai. An apprentice of Rirkrit Tiravanija, one of the festival’s directors, Arunanondchai has been attracting international attention as a representative of the post-internet generation. With this piece, a kind of culmination of his past video works, he conjures up a mysterious story incorporating animism, ecosystems, rituals, tourism, and the impact of American values on Thai culture through vehicles such as the popular “Thailand’s Got Talent” show.

Chata Maiwong《The 4 Novel Truth》(2023) photo: Chie Sumiyoshi

Sanitas Pradittasnee《Garden of Silence》2023 photo: Chie Sumiyoshi

Sanitas Pradittasnee《Garden of Silence》2023 photo: Chie Sumiyoshi

Our next stop, the Chern Tawan International Meditation Center, was a different story. Led by a cute monk who is beloved by young people and somewhat akin to Ikkyu, the witty and tactful monk who is a famous figure in Japanese Buddhism, the Center seeks to introduce visitors to serious Buddhist practice. It’s all a bit confusing, however, in that the facility looks like an organic art village but boasts features such as a meditation tunnel that leads through a wisteria trellis fitted with brightly colored artificial flowers.

Sanitas Pradittasnee’s installation “Garden of Silence,” set in a lush garden with 108 rubber trees, is impressive. Among its three geometrical structures, one building is covered with mirrors that reflect the surrounding landscape and make its contours disappear. When the wind blows, the 1,000 bells hanging among the trees echo faintly. The ever-changing nature around the piece brings about an introspective stillness that evokes the concept of “emptiness” in Buddhist philosophy, which the artist is exploring.

Ernesto Neto《Chantdance》2023 photo: Chie Sumiyoshi

Ernesto Neto《Chantdance》2023 photo: Chie Sumiyoshi

Tarek Atoui《The Wind Harvestors》2023 photo: Chie Sumiyoshi

The Mae Fah Luang Art and Cultural Park was undoubtedly one of the highlights of my trip. It is maintained by a foundation established as a result of the philanthropic activities of Princess Srinagarindra, the mother of King Rama IX, who loved the culture of Northern Thailand and supported its hill tribes. The park includes a museum housing a collection of old Buddhist statues and artifacts. “Mae Fah Luang” (Princess Mother) was the honorary name given to this commoner who became the wife of a prince and who remains revered by the people of Thailand.

The vast, seemingly endless garden is replete with tropical trees that provide color during Northern Thailand’s warm winters and are full of fleshy flowers and fruits. Eventually we reached an open space with an installation by Ernesto Neto, a leading Brazilian artist, whose work consists of a canopy of crimson netting enveloping an array of fragrant spices and unglazed pots. Neto says he was inspired by an experience lying down in a crimson temple he visited in Chiang Rai. And to “express a peaceful ecosystem,” on the ground Neto has added a terracotta basin to distance a peacock from fish, and a clay pot with holes through which plants are growing from the ground.

Working in sound performance and composition, Tarek Atoui is noted for collaborating with local artisans around the world to create sculptural ensembles that draw on traditional instruments. Here he has built a bamboo air circuit inspired by rice paddy irrigation techniques, which plays automatically using objects modified from the tools and instruments of the ethnic minorities of Northern Thailand. The long, tranquil sounds and movements of wood, bamboo, stone, and clay link to a view of a pond with water lilies in the background, evoking a drowsy noon moment in an ancient palace.

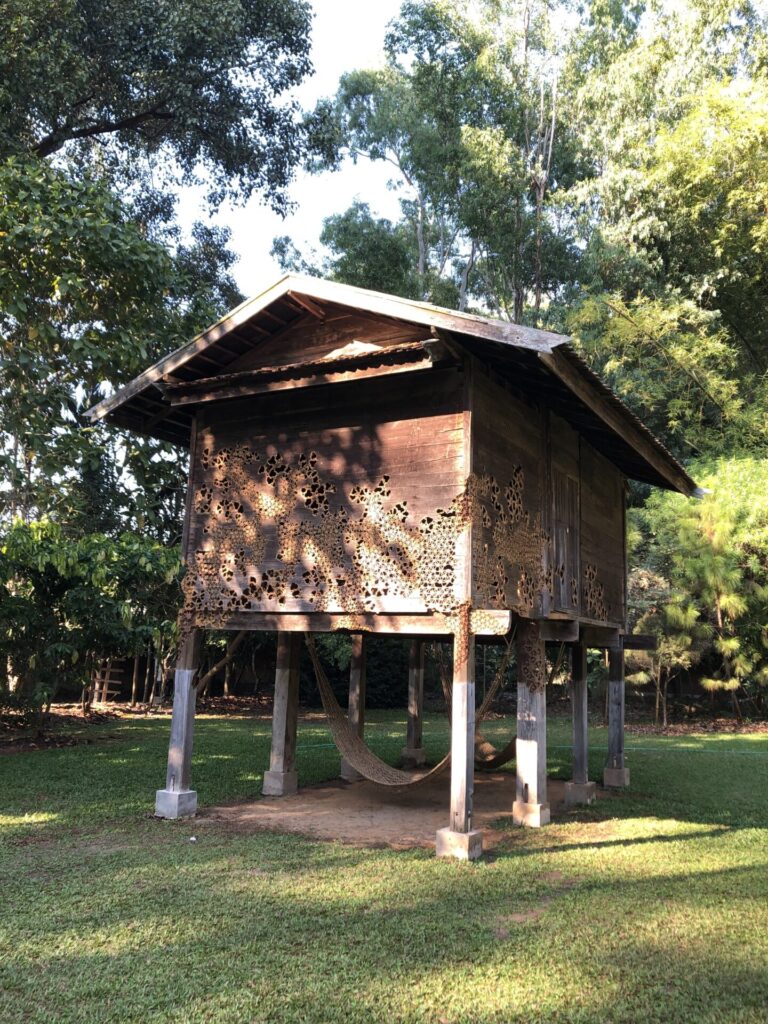

Ryusuke Kido《Inner Light -Chaing Rai Rice Barn-》2023 photo: Chie Sumiyosh

Ryusuke Kido《Inner Light -Chaing Rai Rice Barn-》2023 photo: Chie Sumiyosh

Mae Fah Luang Art and Cultural Park, Kaew Hall photo: Chie Sumiyoshi

Exhibited in the courtyard is a piece by the Japanese sculptor Ryusuke Kido, who has fitted an 80-year-old stilted barn with a sculpture comprising numerous holes of various shapes and sizes that look like they have been carved by insects. The work is exquisite, beautiful, and bizarre, juxtaposing disappearing peasant culture and a virus-infested body.

At the museum, built by master artisans in the old Northern Thai architectural style with carefully selected vintage materials, the rooms for the Biennale exhibition are located next to galleries with collections of Buddhist statues and folk tools from various parts of Northern Thailand. The historic artifacts and contemporary works of art alike are all of high quality and neat, resonating with each other in a graceful and intimate manner. Despite enjoying an insatiable and blissful experience here, going back and forth in time and space in our heads, we still didn’t feel like we managed to spend enough time in this paradise.

crumbling stupa photo: Chie Sumiyoshi

The other main venue of the Biennale encompasses locations in and around Chiang Saen, a small town on the Mekong River bordering Laos and Myanmar. Right next to our chic hotel stood the remains of a crumbling stupa (which had become occupied by cats), and the brick walls that encircle the old town appeared as if held up by sturdy teak trees; this is a city where daily life is seasoned by the kind of beauty possessed only by slowly dying things. According to my friend’s research, people have been living here since the Paleolithic Age.

Ho Tzu Nyen《The Critical Dictionary of Southeast Asia: O for Opium》2022 photo: Chie Sumiyoshi

Nipan Oranniwesna《Then, one morning, they were found dead and hanged》2023 photo: Chie Sumiyoshi

At the Chang Warehouse along the Mekong River, seven artists present works that deal primarily with the area’s geopolitical history. Among these, Singaporean artist Ho Tzu Nyen’s new piece “The Critical Dictionary of Southeast Asia: O for Opium” (2022) quietly makes for a potent remedy. Layered on top of each other like in a muddled consciousness are documentary footage of the history of the Thai–Laos–Myanmar border triangle, once a flourishing opium trade hub known as the Golden Triangle; scenes from opium-related (and likely glorifying) films such as “The Last Emperor” and “Once Upon a Time in America”; and a luscious, demonic animation suggestive of the hallucinogenic effects of narcotics. The “O” for “opium” is also the “O” for “ocean,” suggesting a link to the history of Singapore, the city-state established as a base for maritime trade in Southeast Asia during this infamous “golden” era.

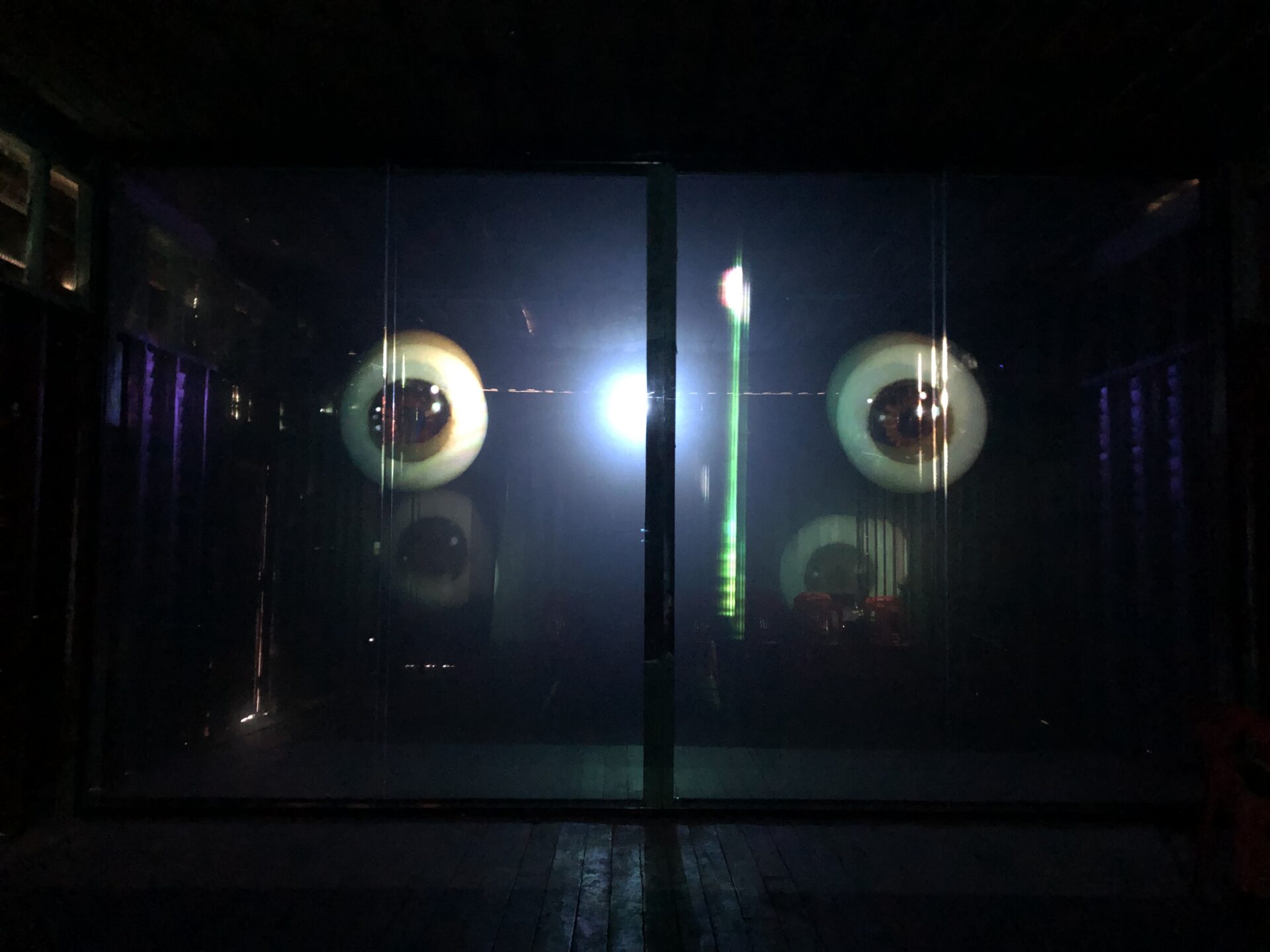

Apichatpong Weerasethakul《Motion Pictures Project at Mae Ma School》 photo: Chie Sumiyoshi

Apichatpong Weerasethakul《Motion Pictures Project at Mae Ma School》 photo: Chie Sumiyoshi

The climax of our journey, and the “eye” that encapsulates the magnetic forces swirling around this place, was Apichatpong Weerasethakul’s installation “Motion Pictures Project at Mae Ma School.” Turning off the national highway onto a side road that appeared to be meant mainly for farmers, we discovered the school in Mae Ma, a village dotted with old houses and rice paddies where black buffalos graze. The artist had initially hoped to place his piece in the ruins of a hospital or something similar, but what his production team found was this abandoned wooden school. (The following draws on excerpts from the exhibition description, translated by Tomo Suzuki.)

In “Blue Encore,” the first motion of the work, the back wall of a bare classroom, unrenovated and uncleaned, is covered with three layers of fabric printed with landscape paintings by a local artist. This threefold curtain eventually begins to move on its own in an analog, landscape-switching animation. The technique is reminiscent of a stage set for traditional Thai performing arts, in which the pictures in the background are rolled up by hand like in a kamishibai storytelling show. Once all the curtains are open, a whiteboard once used in this classroom appears, bearing words written during class: “Let’s create art like we want it to be.”

This is followed by the second motion, “Solarium,” meaning a sunroom with glass walls intended to let light in. A glass screen is set up to divide the space, allowing the audience to view both video footage and a mechanism that lets light pass through from both sides. A part of the footage is from “The Hollow-Eyed Ghost” (“Phi Ta Bo” in the original Thai), a horror movie the artist saw in his childhood. It’s about a doctor who in an effort to help his blind wife kills people, steals their eyeballs, and transplants them to the woman, only for the couple to be haunted by the ghost of the eyeballs’ original owner. Meanwhile, the footage projected onto the same screen from the other direction depicts the movement of light itself. For Apichatpong, elements like the cinema screen, blackout curtains, and the intense light of the projector are themselves key in shaping an image.

The “eyes” and the light footage overlap, darting around the room like devil’s fire. Heavy bass sounds shake the old building, and faint vibrations are felt in the body. The voices of children playing outside and the presence of the forest and its animals feel strangely familiar. The school itself, with its deposited memories of people and nature, is a container that fosters a far more immersive world than any virtual-reality technology. Experiences of mystery and allegory are not something that occur as the result of an artist’s manipulation of technology, but something evoked by having one’s senses stimulated by extremely simple, fundamental conditions.

Michael Lin《Weekend》2023 photo: Chie Sumiyoshi

Tomás Saraceno《Museo Aero Solar》Open source, collaboration project 2007, 2023 photo: Chie Sumiyosh

SHIMABUKU《We are flying》2023 photo: Chie Sumiyosh

Leaving the abandoned school in the village behind us, we headed for the city of Chiang Rai. Having viewed Taiwanese artist Michael Lin’s piece, for which he has decorated a wall of the Old Chiang Rai City Hall building with textile patterns created by the ethnic minorities of Northern Thailand (displayed on panels, unfortunately—Lin wasn’t allowed to paint directly on the wall of this heritage-listed building), we set course for an old warehouse built for the Tobacco Authority of Thailand. Floating in this space is a giant hot-air balloon, made of reused plastic bags and reaching all the way up to the ceiling, by Tomás Saraceno, an Argentine artist and aeronautics researcher. Inside, anyone can use a magic marker to doodle on the balloon. Probably because the venue is next door to a junior high school, some of the scribblings say stuff like “Poop!” and “Idiot!” (in Thai), acting as the finishing touches of the work.

Michihiro Shimabuku, who goes only by Shimabuku, exhibits kites made of super-thin paper decked with nearly life-size drawings of the Biennale’s participating artists and curators. His display includes a video of the kites being flown high in the sky, and I felt like the essence of the Thailand Biennale could be glimpsed in the likenesses of old acquaintances such as Apichatpong, Rirkrit, and Shimabuku himself fluttering together, looking strong and so happy despite their fragile form.

In the parking lot we came across Arto Lindsay’s sound installation, which makes use of a simple system. Despite some underwhelming acoustics in the midst of all the noise, I couldn’t help but sway to the music.

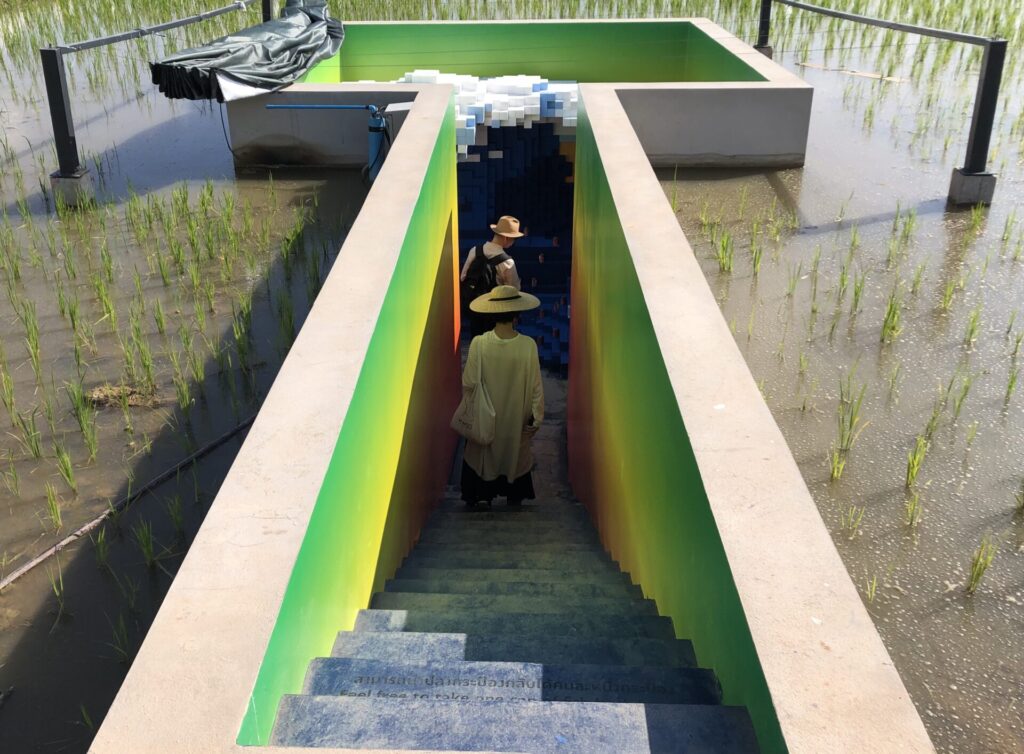

Tobias Rehberger《Nai Nam Mee Pla, Nai Na Mee Khao – In the water there is fish, in the field there is rice.》2023 photo: Chie Sumiyoshi

Haegue Yang《Enveloped Domestic Soul Channels – Mesmerizing Mesh #208》2023 photo: Chie Sumiyoshi

Haegue Yang《Enveloped Domestic Soul Channels – Mesmerizing Mesh #208》2023 photo: Chie Sumiyoshi

Haegue Yang《Incantations–Entwinement, Endurance and Extinction》2022,《The Randing Intermediates- Inception Quartet》2020 photo: Chie Sumiyoshi

Pierre Huyghe《Untitled – Human mask》2014 photo: Chie Sumiyoshi

Our last destination was the CIAM – Chiang Rai International Art Museum, a new facility built in conjunction with the Biennale. Its contemporary structure comes into sight abruptly in a redevelopment zone on the way from the airport to the city center. Several pavilions and installations are set up around the museum: for example, Tobias Rehberger has designed a semi-underground room with stairs descending into a rice paddy. Surrounded by sculptures of waves inspired by Katsushika Hokusai’s ukiyo-e “The Great Wave off Kanagawa,” the space is replete with randomly placed canned fish from around the world, available for visitors to take home with them.

All(Zone), a collective founded in 2009 by architects and designers in Bangkok, has designed a glass-walled outdoor gallery inspired by a greenhouse, which will remain on the site permanently for the people of Chiang Rai to use after the Biennale. The gallery features art by Precious Okoyomon, a Nigerian-American poet based in New York City. Her works have examined the history of immigration and racism as well as the pure joy of everyday life, incorporating elements of performance, poetry, and cooking. Taking up the issue of air pollution caused by fine particulate matter (PM2.5), which has become a serious environmental problem in Thailand, Okyomon has created an installation that addresses this crisis, including smoke pollution from the burning of sugarcane, a plant native to Africa.

Inside the museum, the Korean-born Haegue Yang greets visitors at the entrance with a massive collage mural featuring motifs from traditional Thai crafts and temple gongs. I was again impressed and inspired by her unique sense of beauty and delicate way of engaging with materials of local origin, including the collages exhibited at the Mae Fah Luang museum.

After viewing a series of fascinating works, including Sarah Sze’s dense web of accumulated images and Xin Liu’s near-future sci-fi piece depicting the recovery of rocket wreckage, our final stop, oddly enough, was a hell on earth that made for a scathing conclusion to this journey through the enchanted land of art.

Pierre Huyghe’s “Untitled – Human mask” (2014) is a film shot in Fukushima after the Great East Japan Earthquake. A Japanese macaque in a long wig and a Noh mask is released into an abandoned pub. She wanders around the kitchen and seating area, dangling her legs aimlessly and peering at the decaying food in the cellar. Screened many times in Japan, the film is not a requiem for any particular disaster victim, but a depiction of the role model always forced upon the weak, trapped in the dystopias of disaster, war, and violence that humans bring upon themselves.

Themed “The Open World,” the Thailand Biennale features many works that reflect the serene climate of Chiang Rai and the area’s not always clear-cut history while carefully steering clear of loud and straightforward forms of expression. Although there is a preponderance of works dealing with political and social issues and questions of identity—an overwhelming trend in contemporary art—the specific ways in which these are expressed stand out for their quietness and sensitivity. This is exactly what enables them to slowly permeate the audience’s “skin.” Also relevant here is the fact that the remnants of ancient Northern Thai culture appear to have exercised an exquisite influence on the artists’ creativity. More than any provocative documentary, this edition of the Thailand Biennale is an herbal remedy of an art festival that reveals its full effect over time.

Translated by Ilmari Saarinen

#ThailandBiennale #ThailandBiennaleChiangRai #ThailandBiennaleChiangRai2023

INFORMATION

Thailand Biennale Chiang Rai 2023

Duration: 2023.12.9 - 2024. 4. 30

Venues: Chiang Rai, Chiang Saen and other locations in Thailand