Art writer and editor. She also works as an art coordinator in many exhibitions and projects. The editorial staff of RealTokyo.

Bunka-cho Art Platform Japan was launched in 2018 as a five-year program, with an aim to raise the international profile and promote a greater understanding of contemporary Japanese art. This symposium, organized by the Bunka-cho (Agency of Cultural Affairs, Government of Japan) sought to spark discussion on the role of the tentatively named the Art Communication Center, which the Independent Administrative Institution National Museum of Art aims to open in fiscal 2022. Participants presented examples of how art support is organized in the UK, Austria, and Singapore, with a variety of players from the world of contemporary art then discussing the future of promoting art in Japan.

Opening Talk

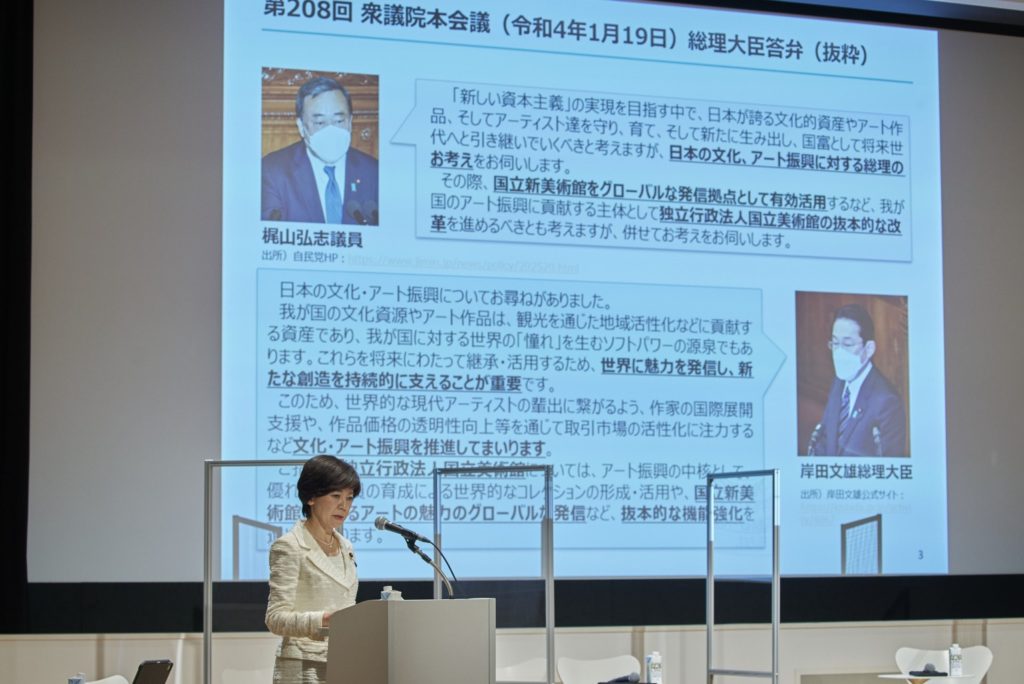

Wanibuchi Yoko (Parliamentary Vice-Minister of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology)

In her opening talk, Wanibuchi Yoko, Parliamentary Vice-Minister of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, referred to an occurrence on January 19 of this year. During a plenary meeting of the House of Representatives at the beginning of the regular Diet session, Representative Kajiyama Hiroshi asked Prime Minister Kishida a question about the promotion of art and the reform of the Independent Administrative Institution National Art Museum.

In his answer, PM Kishida expressed a positive stance on art promotion, responding that “cultural resources and artworks are a source of soft power,” that his government “will push for a sustained form of culture and art promotion in order to convey the appeal of cultural resources and artworks to the world and inspire new creativity” and “will seek a fundamental strengthening of the functions of the Independent Administrative Institution National Art Museum, the core actor in [Japan’s] global art messaging.” Wanibuchi described this as a symbolic event that saw the promotion of art added to the mainstream of key policy initiatives in Japan, and said that a new era in art promotion has now dawned in the country. Introducing the results of a culture-focused public opinion survey, Wanibuchi noted that the number of people in Japan who take an active interest in art is still low. She also pointed out how this lack of interest may be due to art education in schools not adequately teaching people how to enjoy art, and that broadening the base of art viewers and buyers, making the nation’s cultural resources work for the benefit of society, and promoting art in general are important parts of the Independent Administrative Institution National Art Museum and tentatively named the Art Communication Center’s missions.

Bunka-cho Art Platform Japan, operated under a five-year plan initiated in fiscal 2018, has focused on infrastructure projects aimed at enhancing the global reputation of contemporary Japanese art. Meanwhile, the Art Communication Center (tentative name), scheduled to open in fiscal 2022 as a hub for the Independent Administrative Institution National Art Museum, is expected to play a comprehensive role in promoting Japanese art as a whole.

An ecosystem of art is nurtured when the three types of value provided by art—artistic value, economic value, and social value—develop in balance and promote a virtuous cycle. What role can the soon-to-be-established Art Communication Center (tentative name) play in growing this ecosystem in a sound manner? Wanibuchi’s opening talk led the way for discussion in the sessions that followed.

Session 1: “What the new Art Communication Center should aim for”

Kataoka Mami (Director, Mori Art Museum / Chair, Contemporary Art Committee Japan / Executive Advisor, The Art Communication Center (tentative name))

Behind the Bunka-cho Art Platform Japan and the establishment of the Art Communication Center (tentative name) is the state of the world in the post-1990 multicultural era, in which the formerly Western-centric art world has been diffusing its center throughout the globe. Looking at Asia, the number of art museums—such as M+ in Hong Kong, which opened in November 2021—international exhibitions, and art fairs that exhibit contemporary art is continuing to increase. In Japan, on the other hand, a great number of art museums were established between the 1950s and the 1990s, earlier than in other Asian countries, but the subsequent three decades have seen Japan fall behind its neighbors. In 2014, the Bunka-cho finally published its first clarification of the key issues relating to the international promotion of contemporary Japanese art and named the establishment of an art and culture promotion center as a long-term goal.

Art Platform Japan (https://artplatform.go.jp/), the website on which the results of the Bunka-cho Art Platform Japan are being posted, received a substantial overhaul in March 2022, while SHŪZŌ, a database of art museums in Japan, currently lists 140,000 artworks and 147 museums. Images, which were previously difficult to include, are now being added as thumbnails, while assistance for international research into contemporary Japanese art is being provided through a Readings section including both previously untranslated texts and existing translations on postwar art. In addition, the database includes a survey of contemporary Japanese art exhibitions, a database of gallery information, and archived videos of events such as symposiums, with more content being added at a steady pace. The Bunka-cho Art Platform Japan is in its last year of operation, and part of its outcomes are expected to be taken over by the Art Communication Center (tentative name).

The Art Communication Center (tentative name) concept

The history of Japan’s national art museums began in 1952, the year in which the country regained its sovereignty after the post-World War II occupation, when the National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo was established (initially under the name National Museum of Modern Art). Since then, a total of six national museums as well as the National Film Archive of Japan have been established, with these institutions conducting their respective programs under the auspices of the Independent Administrative Institution National Museum of Art. The Art Communication Center concept aims to link these institutions in a new way by focusing on the following four pillars:

- Formation and effective utilization of a national collection: Making available the collections of museums throughout Japan, including those of the national museums, and publicizing them domestically and internationally as a national collection.

- Creation of a database and network for informational materials: Functioning as an information hub that distributes relevant materials through an international network in order to enhance the international reputation of Japanese art.

- Collection and implementation of educational information, development of human resources: Promoting surveys and research on learning, and collaborating with actors in fields including education, medicine, and welfare.

- Social collaboration: Bringing art and society together by building relationships with local communities and economies, and promoting social contributions through art.

Furthermore, Kataoka hopes to add the function of international communication, which the Bunka-cho Art Platform Japan has been performing, to this list.

“We live in an era in which things must be horizontally connected with each other,” she said. “We’ve only just begun to discuss how to join the various national art museum institutions together and how to perform the function of serving as an international point of contact for promoting Japanese art.”

In order to gain perspectives on the direction the Center might take, Session 2 featured presentations of three case studies from overseas.

Session 2: International Case Studies of Art Support

UK: Devika Singh (Curator, International Art, Tate)

Collections are not static.

The Tate consists of four sites—Tate Britain, Tate Modern, Tate St. Ives, and Tate Liverpool—but has only one collection: the national collection of British art from the 1500s to the present, as well as international modern and contemporary art. The collection counts more than 70,000 artworks, with about 500 works being added each year. According to Singh, the impact of Britain’s imperial history on the national collection should not be forgotten.

“The collection is never static. Not only because it keeps growing, but because artworks are constantly being reinterpreted.”

Tate Modern was opened in 2000 with the mandate of displaying modern and contemporary international art. Singh brought up Century City, a group exhibition that was held in 2001, as indicative of the museum’s perspectival shift from a focus on the UK to a wider view on the world. In the exhibition, cities including Moscow, Lagos, New York, and Paris were chosen to represent a particular decade of the 20th century. It was the first major exhibition in a European museum to incorporate a multicentric perspective, including by choosing both London and Bombay to represent the 1990s.

One of the mechanisms pertaining to the Tate collection is the acquisition committee system. There are eight such committees, which are regionally focused except for the photography committee, and they bring together benefactors who support the acquisition of artworks for the museum. These committees are what make an international collection possible. As artworks are acquired in perpetuity, collection care, or conservation and storage of the works, forms a part of the thinking that goes into an acquisition.

The collection is always displayed transnationally. Since its opening, Tate Modern has distinguished itself through displaying artworks thematically rather than chronologically. Instead of trying to present the linear advancement of the history of art, Tate Modern has opted for a thematic approach, bringing together art from varying regions and times, enabling it to juxtapose artworks in a transnational as well as a transhistorical way—in a manner, according to Singh, similar to the way artists borrow and engage in dialogue with artworks from different regions and different times. She illustrated this point through examples of themed rooms used to exhibit the collection.

A new perspective on global history

Hyundai Tate Research Centre: Transnational

Tate Modern is currently (until August 29) hosting an exhibition titled Surrealism Beyond Borders, which challenges the established narrative of the movement as focused on 1920s Paris, taking a wider view on surrealism around the world. The Hyundai Tate Research Centre: Transnational, which Singh works with, supported the research that undergirds this exhibition.

One of the aims of this research center is to redefine the Tate collection, shifting the narrative away from the traditional focus on Western Europe and North America by highlighting new perspectives on global art histories. For its annual conference in 2020, the center collaborated with the Mori Art Museum and Sophia University to present “From Alexandria to Tokyo: Art, Colonialism and Entangled History,” an attempt to address the perspectives of art, non-European colonialism, and experiences of domination. As an institution engaging with the legacy of British imperialism, it is crucial for the museum to incorporate the perspectives of the dominated, and it brings together curators from different fields, regions, and specializations for this purpose. The Tate currently has 13 curators, as well as adjunct curators based in various cities and curators specializing in diasporic and indigenous art.

“Working transnationally, as a UK national institution in London, relates to what we do, to who we are, as well as to whom we speak to. The diversity of our audiences, in terms not only of who they are, but what their expectations are for the museum, is very much at the forefront of what we do.”

Austria: Jasper Sharp (Director of Phileas)

Founded in 2014, Phileas seeks to strengthen the voice of Austrian and Austrian-based artists on the international landscape. According to founder Jasper Sharp, the reasons the organization was set up were that many artists who work in Vienna felt they were missing contact with the rest of the world, and that Austria’s public funding system for the arts is passive, waiting for applications rather than actively seeking opportunities for artists. Phileas reaches out to the world to help make international exhibition opportunities possible for artists, who in Austria are already receiving sufficient public support and have opportunities to exhibit their work domestically.

A rarity in Austria, Phileas is a private organization funded by philanthropists based both within and outside the country. They not only provide funding, but are also welcomed as collaborators into the production of various projects and activities. For example, were Phileas to produce an exhibition for the Gwangju Biennale, the funders would help select the project to be funded, visit the studio of the artist, and travel to the opening of the project.

Phileas supports artists in many ways, including during the process of creating artworks for museums and/or international exhibitions. They contact arts institutions around the world directly, propose to collaborate, and respond to concepts with artist portfolios. They then organize studio visits in the hope that curators will find something to include in their exhibitions. So far, Phileas has collaborated three times with the Venice Biennale and four times with the Liverpool Biennial, and has also sent Austrian artists to the Lyon and Sydney Biennales. Finally, they seek to donate the works produced to museums around the world. Phileas grants are almost always made jointly with the Austrian Ministry of Education, Arts and Culture at a near 50-50 ratio. This allows the government to direct its funding toward a higher quality of support that is more in line with the realities on the ground.

Annual activities

Phileas’s activities include a year-round visitor program, which involves arranging for curators from abroad to visit artists’ studios, galleries, and other spaces for research. They have also initiated a program to invite art critics to Austria, and are officially beginning to invite museum groups as well. And in an effort to help up-and-coming artists, they publish a series called “First Monographs,” the fruits of which can be sent out to people around the world to promote the artist.

In 2022, Phileas will be opening its own exhibition space in the center of Vienna, which will serve as a venue for events including exhibitions and projects, talks and performances, and film screenings. It will also be a research center for international curators visiting Austria. Additionally, Phileas is preparing to offer opportunities for curators working in Austria to spend time abroad and is looking into providing an internship program—all with a staff of six people.

“Our activities resemble filling in the missing pieces of a jigsaw puzzle,” says Sharp, who holds that Phileas’s activities have helped double the presence of Austrian artists abroad compared to five or six years ago.

“We’re having an ongoing conversation about how we can tie the activities of government, artists, curators, and philanthropists together in a way that joins the dots in the most fruitful manner.”

Singapore: Horikawa Lisa (Director (Curatorial & Collections), National Gallery Singapore)

The National Gallery Singapore was established in November 2015 after a decade-long renovation of the two colonial-era buildings that house the institution: the former Supreme Court building and the City Hall, both located in the heart of Singapore. The museum holds the world’s largest collection of modern and contemporary art from Singapore and Southeast Asia, a collection that reflects the significance of diversity and inclusiveness in the multicultural, multi-ethnic society that is Singapore. The National Gallery interprets Southeast Asian art history in the context of global art history and conducts research and programming activities aimed at presenting the art of the region to the rest of the world.

According to Horikawa, the institution views history not as something static, but as the subject of ongoing investigation, questioning, and rewriting. Interestingly, this view is similar to that presented by Devika Singh of the UK’s Tate, a museum in the country that formerly ruled Singapore.

The distinctive evolution of Southeast Asian museums

Many museums in Singapore and other Southeast Asian countries have their origins in colonial-era museums. As such, the way in which they collect and categorize art and artifacts and write history has been inextricably tied with the colonial period. After independence, many of these countries immediately sought to reclaim their identity by redefining their history, including by building museums to showcase their own collections and stories. Singapore, too, established the National Museum Art Gallery in 1976, followed by the Singapore Art Museum in 1996 and the National Gallery Singapore in 2015. Collections from the 19th and 20th centuries are now managed by the National Gallery Singapore, while works of contemporary art mainly from the past two decades are the domain of the Singapore Art Museum (how to differentiate the two institutions’ collections from each other is a matter of ongoing consideration). Unlike collections in other Southeast Asian countries that concentrate on each country’s own art history, the National Gallery Singapore’s collection takes as its focus the entire Southeast Asian region: the 8,000-plus works cover the Malay Peninsula and the wider region, and are organized around three main themes: Singapore, Southeast Asia, and ink art.

Forming, managing, and storing collections in an organized manner: Singapore’s cultural policy

The national art museum of Singapore comprises three public institutions, the National Gallery Singapore, Singapore Art Museum, and STPI (Singapore Tyler Print Institute), which form a private entity called the Visual Arts Cluster. This semi-public, semi-private structure allows for flexibility in museum operations, as well as shared use of personnel and facilities.

A feature of Singapore’s cultural policy is that the entire national collection is managed and administered by the National Heritage Board (NHB), which has a section tasked with the conservation and restoration of artworks. Works not on display are kept at the Heritage Conservation Center and managed by specialist registrars and conservators. Having the national collection under one umbrella facilitates cross-museum collection access and information sharing on curatorial research and collection management. This also contributes to the utilization of cultural assets in cooperation with art education initiatives and schools. In addition to each museum’s acquisition review committee, a National Collection Advisory Panel has been established to prevent conflicts of interest and to ensure a unified approach to collection strategy.

The National Gallery Singapore is committed to working with both local and international stakeholders and partners on joint research for traveling exhibitions and programs. Rather than creating pre-packaged traveling exhibitions, the institution seeks to jointly produce exhibitions that connect various topics and explore regional narratives. It also organizes workshops and discussions that bring together experts from across Asia.

“For the National Gallery Singapore, which aims to reimagine art from a postcolonial perspective, regional collaboration and cooperation is an invaluable process,” says Horikawa.

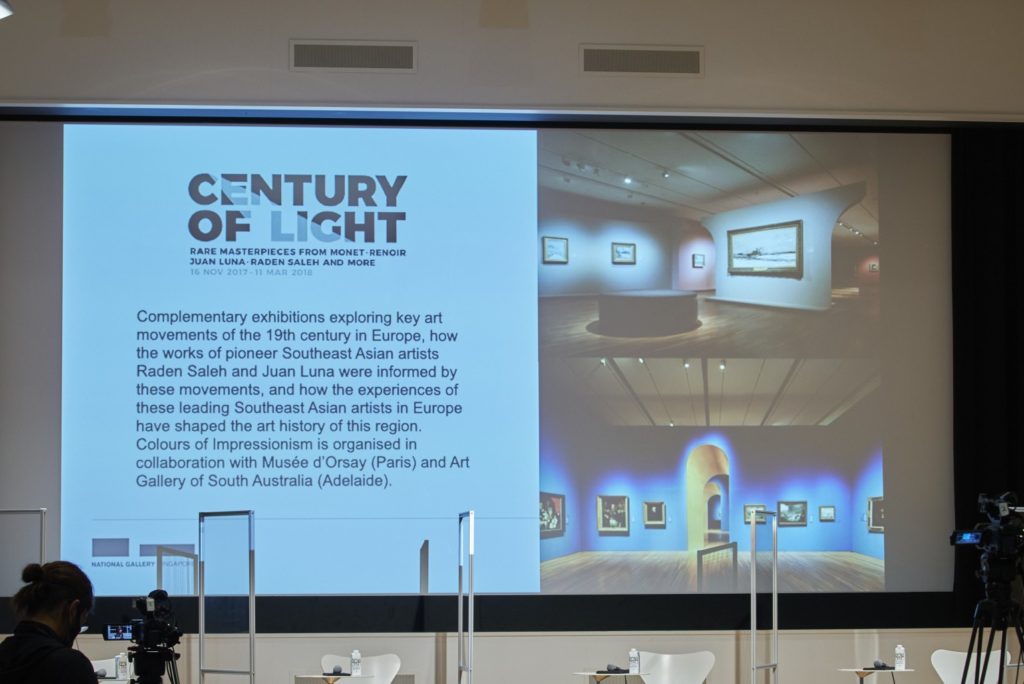

”Century of Light,” an exhibition co-presented with the Musée d’Orsay and the Art Gallery of South Australia, 2018.

Session 3: Discussion/Q&A – “The Roles and the Mission of Japan’s New Art Communication Center (tentative name)”

Panelists:

Hosaka Kenjiro (Director of the Shiga Museum of Art (SMoA))

Koike Ai (Representative of THE CREATIVE FUND, LLP)

Shiomi Yuko (Director of the Arts Initiative Tokyo (AIT))

Tsubaki Noboru (Contemporary Artist)

Uematsu Yuka (Vice Chair of the Contemporary Art Committee Japan, Chief Curator of the National Museum of Art, Osaka)

Moderator: Kataoka Mami

Following the presentations of the three international case studies, the symposium panelists, who are involved in the contemporary Japanese art scene in a variety of ways, debated the roles of the new Art Communication Center.

Hosaka Kenjiro, director of the Shiga Museum of Art, reflected on his experiences during his tenure at the National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo, arguing that it is time to rethink Japanese museum collections—which are usually thought of on a museum-by-museum basis—in order for them to keep pace with the momentum of museums elsewhere in the world. He said that the Tate’s “one collection” approach is very illuminating, and that the challenge for the future is how to make use of the social advantages inherent in a national collection. Hosaka also touched on special exhibitions that tour from one country to the other, holding that the Art Communication Center has great potential to play a role in this area.

Koike Ai, who has a close relationship with many collectors, was intrigued by the structure of the Tate’s eight acquisition committees. For collectors, the opportunity to be involved in shaping museum collections is very attractive. She emphasized how it is desirable for art experts and collectors to work together to push Japanese art out into the world, and expressed hope that the government would support collectors through legislation such as tax breaks for the donation of artworks, and that art professionals would become more interested in the business side of things.

Shiomi Yuko of AIT, which works with corporations to support artists, drew attention to the efforts of the Hyundai Tate Research Center. She noted the center’s transnational perspective and its relationship with Hyundai, a corporation, and said that the keywords “linkage” and “circulation” came to mind. Shiomi also mentioned the global climate crisis and its challenges for art, and expressed hope that the new Art Communication Center will play a leading role in this area, which has not yet seen sufficient attention in Japan.

As an artist and educator, Tsubaki Noboru has been working in the field of education to create a platform that would help produce new artists. For him, the problem of universities not being able to update themselves is indicative of an issue common to all Japanese organizations. He pointed out that the success of the proposed Art Communication Center depends entirely on the organization’s ability to repeatedly “upgrade” itself.

Uematsu Yuka, curator at the National Museum of Art, Osaka and a member of the Bunka-cho Art Platform Japan, noted that with 70 years having passed since the establishment of Japan’s first national museum, the time is ripe for a change in the roles of the country’s national museums. However, she argued that careful consideration is needed to determine what sort of “update” should be implemented in Japan, where the situation differs from that of the Tate and Singapore in terms of both budgets and scale.

The importance of a transnational perspective

Kataoka Mami touched on the importance of putting forth transnational value while taking into account both the state of domestic cultural affairs and overseas trends. On that note, Hosaka brought up two exhibitions: “Sunshower: Contemporary Art from Southeast Asia 1980s to Now,” held jointly by the Mori Art Museum and The Art Center, Tokyo in 2017; and the following year’s “Awakenings: Arts in Society in Asia 1960s-1990s” at the National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo. While both exhibitions sought to reinterpret Japanese art in the context of Asian art, they were unable to present this as a possible future policy for the Independent Administrative Institution National Museum of Art as a whole. He pointed out the need for a comprehensive strategy, including in terms of PR, to communicate developments in Japan.

As Koike pointed out by saying that “Contemporary art cannot be discussed only in Japanese terms while ignoring the global context,” cross-border collaboration is becoming increasingly important in our unstable world. Shiomi chimed in by saying that “Artists are already acting transnationally, and I think it’s important to take their knowledge onboard.” Tsubaki, meanwhile, expressed hope that government would “catch up” with what artists are doing on the ground. “We need to update the current situation by increasing the number of intermediaries and having curators and administrators become multi-players and work together,” he said.

Tate Modern’s attempt to reinterpret the history of the British Empire by developing its collection transnationally; Phileas’s practical activities, in which the public and private sectors join hands to create win-win relationships that have an immediate effect; and Singapore’s cultural policy, under which the National Heritage Board coordinates between multiple national museums to administer and manage the national collection. All three cases contained many instructive lessons for Japan’s concept of an Art Communication Center, but at the end of the non-stop two-hour symposium, the role expected of the new center felt endlessly vast.

In conclusion, Uematsu warned that “If we expect the Center to take responsibility for everything, the picture of the institution may become hazy. Going forward, we ought to think about what it is that should be done and what will be needed, all while listening to a wide variety of voices.”

Concrete discussion concerning the Art Communication Center is still in its early stages. As the new institution builds on the achievements of the Bunka-cho Art Platform Japan from the past five years, I look forward to seeing a diligent approach to the issues at hand and steady implementation—as if fitting the pieces of a jigsaw puzzle together one by one.

Translated by Ilmari Saarinen

As of March 28, 2023, the Art Communication Center (tentative name) was established as the “National Center for Art Research (NCAR)” (Director: Mami Kataoka).

INFORMATION

Art Platform Japan Symposium

"The Globalization of the Art World and Japan: The expected roles and the mission of Japan’s new art communication center"

Date: 2022.3.11

Organizer: Bunka-cho Art Platform Japan

Photo: Kaneda Kozo