Odawara Nodoka is a sculptor, researcher, critic. Born in Miyagi Prefecture, she holds a Doctor of Arts from Tsukuba University. Her exhibitions include Kindai o chōkoku/chōkoku suru Tsunagi and Minamata hen [Overcoming/Sculpting Modernity: Tsunagi and Minamata], a solo exhibition at Tsunagi Art Museum in 2023, and the Aichi Triennale 2019. Solo publications include: “Kindai o chōkoku/chōkoku suru” [Overcoming/Sculpting Modernity] (Kodansha, 2021) and “Monument Theory: Sculpture as an Ideological Challenge” (Seidosya, 2023).

©Rikimaru Hotta / New National Theatre, Tokyo

Magma and Menstrual Blood: Anish Kapoor’s Set Design in “Simon Boccanegra”

The New National Theatre recently concluded performances of its inaugural production of the opera “Simon Boccanegra” (premiered in 1857, revised in 1881) by Giuseppe Verdi (1813–1901). Co-produced by the Finnish National Opera and the Teatro Real of Madrid, the production is scheduled to tour Helsinki and Madrid after its premiere in Japan.

Consisting of a prologue and three acts, the work follows the life of the protagonist, Simon Boccanegra, with the prologue set 25 years before the main story. The setting is the fourteenth-century Republic of Genoa, where Simon Boccanegra was the first Doge (head of state). The main storyline consists of Boccanegra’s dramatic reunion with his estranged daughter Amelia (born Maria) and the protagonist’s tragic death, while the backdrop of these events is a class struggle between Genoa’s plebeians and patricians.

©Rikimaru Hotta / New National Theatre, Tokyo

In the Republic of Genoa, which existed from 1005 to 1797, the historical Simone Boccanegra became the first Doge at a time when four of the city-state’s leading aristocratic families had split into rival papal and imperial factions, while these patricians were opposed by the plebiscite faction made up of merchants and commoners. Boccanegra was elected the first Doge of Genoa in 1339, was once ousted in 1344 due to a patrician conspiracy, but was reinstated in 1356. He died in 1363 after having his wine poisoned at a banquet.

Verdi’s version of the life of Simon Boccanegra is an interesting one, in which Boccanegra, a privateer with no political ambitions, becomes the first Doge of Genoa in order to fulfill his love affair with Maria, the daughter of his political opponent, the aristocratic Fiesco. Boccanegra is elected Doge with the help and encouragement of the plebeian Paolo, but his love for Maria ends tragically, with her death and Simon’s separation from his own child. Twenty-five years later, Boccanegra is reunited with his daughter Amelia and reconciles with Fiesco, only to be poisoned and killed at the hands of Paolo, who is a secret admirer of Amelia’s. The play’s plot is noted for its complexity, but in this production, the reunion and reconciliation—taking place amidst a vortex of class conflict and betrayal—stand out with their purity.

©Rikimaru Hotta / New National Theatre, Tokyo

This impression may be due in large part to the fact that the stage design is the work of Anish Kapoor. As producer Pierre Audi noted, choosing a contemporary artist to handle the stage design for a Verdi opera is a rare thing.

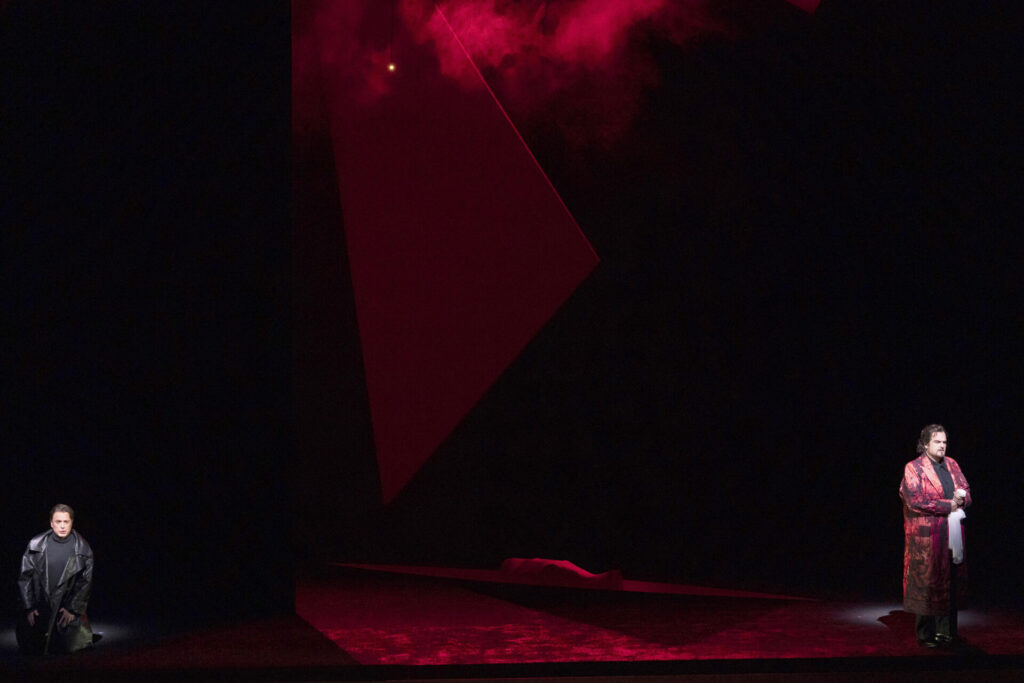

For Audi’s production of the story of Simon Boccanegra, Kapoor came up with three main scenographic devices. First, the stage for the prologue features several triangular objects. Initially gloomy and achromatic in the darkness, they are illuminated the moment Boccanegra, a sailor, becomes Doge, and are revealed to depict the colors of the flag of the maritime nation of Genoa, as well as the sails of a ship. Being separated from his loved ones and the glory of becoming the first Doge of Genoa are the factors that turn the course of Boccanegra’s life, and the contrast between the two is vividly reflected in the stage design.

©Rikimaru Hotta / New National Theatre, Tokyo

The events of the third act, 25 years later, take place on a stage above which a giant volcano appears to be hanging upside down. This striking and symbolic overturned mountain was inspired by the unfinished drama “The Death of Empedocles” by the German Romantic poet and philosopher Friedrich Hölderlin. This play, which had a profound influence on Nietzsche, is about the life and thought of Empedocles, an ancient Greek philosopher who lived near Mount Etna in eastern Sicily and committed suicide by throwing himself into its crater.

Mount Etna is the largest active volcano in Europe and the highest mountain in Italy south of the Alps. It has been the source of many legends in Greek and Roman mythology; in one tale Etna’s eruptions are attributed to the struggles of the monster Typhon, who was defeated by Zeus and buried under the mountain, and in another story the giant Enceladus, who was vanquished and entombed by Athena, keeps spitting flames from his prison underneath the peak.

©Rikimaru Hotta / New National Theatre, Tokyo

In this production, when Boccanegra dies, Mount Etna erupts and both the protagonist and the stage are enveloped in a material reminiscent of lava. Such stage design and staging lend the work a mythological imaginative power in the vein of “The Death of Empedocles,” which has been described as a “struggle against the form of tragedy,” i.e. an attempt to transcend the human perspective in this genre. Even more surprising is the appearance of a jet-black sun in the middle of the stage, replacing the upside-down Etna after its eruption. This reminded me of Kapoor’s “The Origin of the World,” and I’m sure I’m not the only one who thought it also resembled a reversal of the Japanese flag.

I’d like to draw another corollary to this black spot. There’s a newly developed material called Vantablack that absorbs 99.8 percent of all light and is said to be blacker than even a black hole. Kapoor has held a monopoly on the rights to use this material in paintings and sculptures since 2014. Although a black coating with 99.995 percent light absorption capability—a higher percentage than Vantablack’s—was developed by researchers at MIT in 2019, Kapoor’s Vantablack monopoly remains controversial.

This production of “Simon Boccanegra,” through its stage design and while referencing “The Death of Empedocles,” appears to aim at de-anthropocentrism by linking a tragedy of class society with the larger-than-human phenomenon of a volcanic eruption. The unexpected allusion to the Vantablack controversy via the final act’s black spot may have been unintended, but that fact included, it made for an interesting stage proposition.

Anish Kapoor was born in Bombay (now Mumbai) in 1954 to a mother from Baghdad’s Jewish community and a father who hailed from a region spanning northwest India and northeast Pakistan. He received his primary education in Dehradun, studied electrical engineering on a Kibbutz in Israel, and moved to England to study art at Chelsea College of Art and Design. He represented Britain at the 1990 Venice Biennale, received the Turner Prize in 1991, was awarded the CBE of the Order of the British Empire in 2003, and in 2009 became the first living artist to hold a solo exhibition at London’s Royal Academy of Arts.

Despite Kapoor’s impressive accomplishments, not much has been said about his complex background. It should be noted here that the article by cultural scholar Hiroki Yamamoto, included in the official brochure of the production, delves into this point.

Several of Kapoor’s works can be seen in Japan. The 21st Century Museum of Contemporary Art, Kanazawa has the aforementioned “The Origin of the World” (2004) on permanent display, and the same is true for “Mountain” at Faret Tachikawa, completed in 1994 in the Tokyo suburb of Tachikawa. Many temporary exhibitions have also explored Kapoor’s work, among them “Anish Kapoor: Looking at the Deprived of Freedom—The Future of Surveillance Society” (curated by Takayo Iida), on view through January 28, 2024, at the GYRE Gallery in Omotesando, which provides great insight to Kapoor’s stage design in “Simon Boccanegra.”

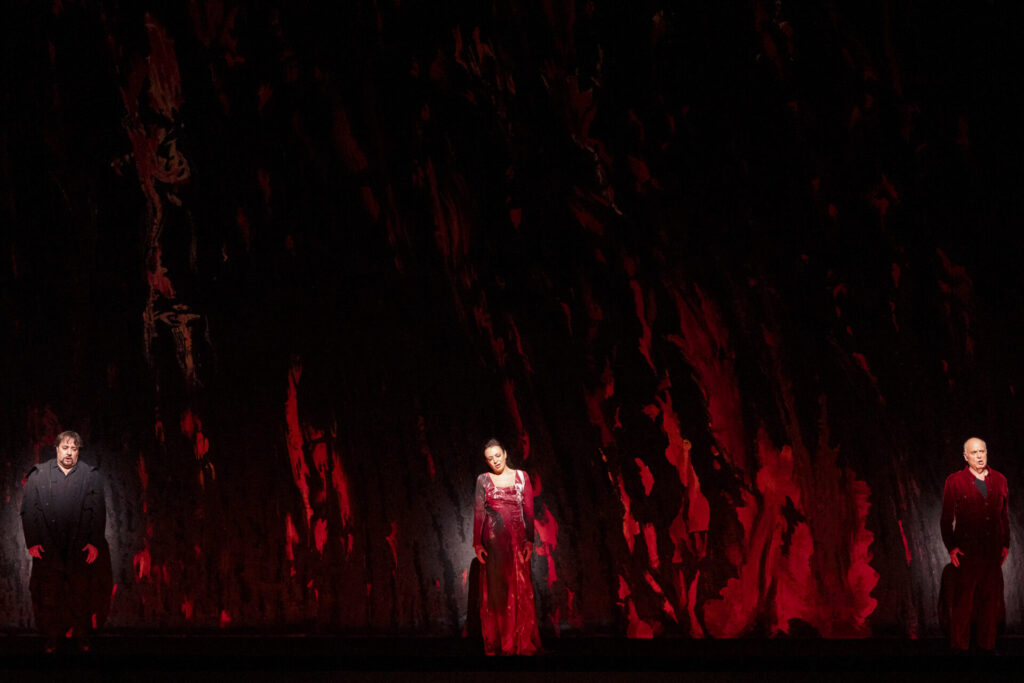

At that exhibition, visitors can see both two-dimensional works from the same series as the drawings that Kapoor created as part of the stage design for “Simon Boccanegra,” and three-dimensional works with a deep connection to the organic objects used as artistic devices in the opera. The latter, which were also employed to depict the magma on stage, can be viewed at a much closer distance than would be possible in a museum. When seen up close like that, the works appear to resemble clumps of menstrual blood.

©Rikimaru Hotta / New National Theatre, Tokyo

In Verdi’s “Simon Boccanegra,” named after its lead character, the last word uttered by the dying Boccanegra is “Maria”—both the baptismal name of his daughter, whom he was separated from for 25 years, and the name of his beloved, with whom he could not share his life. The duality of the union and dissolution of nature and artifice is the subject of “The Death of Empedocles,” which, despite three rounds of revisions by Hölderlin, was left unfinished, without ever describing the hero’s plunge into the crater of Mount Etna. To Kapoor’s stage design, which lends “Simon Boccanegra” a finality left undepicted in “The Death of Empedocles,” I’d like to superimpose menstrual blood as a signifier of the cycle of life. Why was Mount Etna overturned? Could the upside-down mountain not be thought to resemble a womb? Thanks to Kapoor’s stage design, this opera, which begins and ends with a name, can be appreciated as such a cyclical narrative.

References:

Hiroshi Hatakeyama: “Unmei no ‘guyusei’ kara higeki no ‘rinen’ he: kakarezaru higeki ‘Empedocles no shi’” (“From Accidents of Fate to the Idea of Tragedy: ‘The Death of Empedocles’ as Unwritten Tragedy”); The semiannual periodical of the Faculty of Arts and Sciences, Department of English and Department of Foreign Languages, Komazawa University; 2017

Friedrich Hölderlin: “The Death of Empedocles” (Japanese translation by Tomoyuki Tani, Iwanami Bunko, 1997)

Translated by Ilmari Saarinen

INFORMATION

Giuseppe Verdi “Simon Boccanegra”

Period: November 15 - 26, 2023

Organized by: New National Theatre, Tokyo / Japan Arts Council / Agency for Cultural Affairs, Government of Japan

Presented by New National Theatre Foundation, Japan Arts Council, Agency for Cultural Affairs, Government of Japan

Co-production with: Finnish National Opera and Ballet, Teatro Real Madrid

Produced by: New National Theatre, Tokyo

Conductor: ONO Kazushi

Production: Pierre AUDI

Set Design: Anish KAPOOR

Costume Design: Wojciech DZIEDZIC

Lighting Design: Jean KALMAN

Stage Manager: TAKAHASHI Naohito

Performers:

Simon Boccanegra: Roberto FRONTALI

Amelia (Maria Boccanegra): Irina LUNGU

Jacopo Fiesco: Riccardo ZANELLATO

Gabriele Adorno: Luciano GANCI

Paolo Albiani: Simone ALBERGHINI

Pietro: SUDO Shingo

Un capitano dei balestrieri: MURAKAMI Toshiaki

Un'ancella di Amelia: SUZUKI Ryoko

Chorus: New National Theatre Chorus

Orchestra: Tokyo Philharmonic Orchestra