■Dance critic and a director of Japan Dance Plug Co. Ltd.

■Contribution:”Monthly BRAVO(my own serial page)”,”DANCE MAGAZINE”,”ASAHI SHIMBUN(Newspaper)”

■Book list:”PERFECT GUIDE BOOK of Contemporary Dance”,”Dance Bible” and more.

■Festival Advisor, Jury of Competition:”Dance New Air”,”Fukuoka Dance Fringe Festival”,”Hokkaido Dance Project”,”Odoru AKITA”,”Dancers’ Nest”,”El Sur Foundation ”,”Tokyo Metropolitan Theater ”,”Seoul International Choreograph Festival”,”New Dance for Asia(Seoul) & Asian Solo & Duo Challenge for MASDANZA”

Saori Hala is active in Tokyo and Berlin (completed her studies at Universität der Künste Berlin in March). This piece is an hour-long “self-documentary performance” revolving around the relationship between the dancer and her father Takeshi Hara, a musical dancer in the 1960s, whom Hala more or less never met for 25 years.

Before leaving Japan for Germany in order to enroll at the Universität der Künste in 2015, Hala performed the piece “d/a/d” (with Fuyuki Yamakawa and Tomomi Oda). This was an occasion for the artist to reunite and restore her relationship with her father. I had the opportunity to meet Takeshi Hara, who attended the performance in a wheelchair, but suddenly passed away a few days later. From a recording of a conversation with her father just prior to “d/a/d,” and various other documents, Hala composed “Da Dad Dada” (premiered in Germany in 2017), a dance piece on the theme of “absence.”

photo by bozzo

Audience seats are arranged in two separate groups sandwiching the acting area at a 90-degree angle, where 13 young dancers, all dressed in white, are sitting at the beginning. Only Hala herself is dressed in black, and starts the performance lying on the floor of the stage.

Once she gets up on her feet, supertitles telling about her father in his musical days appear, accompanied by an audio recording of the dancer’s conversation with her father shortly before his death. Takeshi Hara had starred in “Asphalt Girl” (1964), a colorful movie that was riding the wave of the musical boom in a rapidly recovering Japan after the war. Here the aging dancer is interviewed by his daughter about those glamorous times, and while recalling his appearances in movies and the Kohaku song festival (nationally popular year-end TV program), Hara repeatedly enthuses about how beautiful his daughter has gotten. ”How is your German boyfriend?” “I don’t have one!” The conversation continues in an overall friendly atmosphere.

But that preestablished harmony is abruptly destroyed.

photo by bozzo

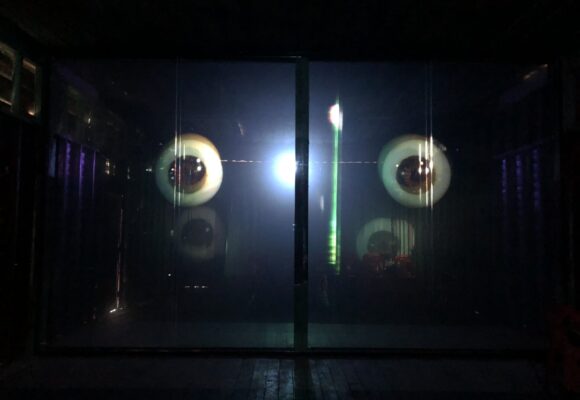

In a box in a corner of the stage that functions as a dressing room, Hala is smoothing down her hair and putting on makeup, while images of her father begin to loom. As the wall of the box is a one-way mirror, the audience can see everything, along with additional footage of her that is filmed from the back and projected onto the wall. Hala repeats the lines she speaks in the conversation with her father – suggesting that her part in the conversation is done live on stage and not just an audio playback, which has the effect that the piece at large is gradually infiltrated with Saori Hala’s physical presence.

Then she suddenly throws off her “good girl” disguise, and begins to express her feelings toward her father in a denouncing manner. “While you were dancing in the spotlight, I was always waiting for you to come home. When dragged onto the stage I always played the ‘beloved daughter.’ But I was living in the shadow, together with my mother. Do you know what they called me at school? I…got no love!”

When making oneself the subject matter of a work, the most difficult part is the separation between the “self that speaks” and the “self that is spoken about.” This is because from the spectator’s perspective, it’s all about “someone else.” Commonplace talk is boring, and cheap ”tragic hero appeal” is a mood killer. In Japan, dance pieces themed around the respective artist’s real life are extremely rare.

However in Europe there are many. The idea behind that is that dance is not just a form of showcasing techniques of moving the body, but something that investigates the “performer’s presence on the stage.” ”DESH” is a piece in which the British-Bangladeshi dancer Akram Khan explores his identity, and in ”Veronique Doisneau” (by Jerome Bel), an about-to-retire Paris Opera sujet reflects on her life as a ballet dancer. There are in fact too many examples to mention.

In this respect, Hala has obviously absorbed some of the positive European practices, as she handles the matter of separation with excellence. The intervention of the ”Asphalt Girl” creates a sense of distance that enables her to talk about her father with no attachment, while the mother as an element that is “referred to but doesn’t appear as a personality” functions well in terms of keeping the emotional relationship with her father down to a minimum. This is exactly why the risky expression of emotions comes across with the sharpness of a knife.

Considering the 25 years they didn’t spend together, and the sudden death after their reunion, her father’s ”absence” must have been part of Hala’s ”daily routine.” Nonetheless, there are inseparable things that unavoidably pile up. The face that comes to resemble that of her father the older she gets; the choice of a career as a dancer just like her father; the decision to change her family name to her father’s (although choosing to spell it “Hala”)… All these things gradually highlight the way Saori Hala has been rejecting yet at once following in the wake of her father.

Making an about-turn from the onerous expression of emotions, together with the white-dressed young dancers she starts performing a show dance in bright spotlight, just like that in ”Asphalt Girl.” Here we see Hala do the same dance, with the same face as her father, whereas her life in the shadows is clearly outlined the brighter the lights get. As if embodying the world of bright lights that her father once lived in, the white-dressed dancers eventually collapse one after another.

Having started the performance as a black shadow on the floor, at the end Hala is the only one standing up straight on the stage. It is an ending that makes one feel how light and shadow are reversed, while conveying the strong will to live with both of them.

(performance at BUoY Art Center Kitasenju, March 30)

Translated by Andreas Stuhlmann

『アスファルト・ガール』

DVD¥2,800(税抜)

発売・販売:KADOKAWA

©KADOKAWA 1964